Review by Frank Plowright

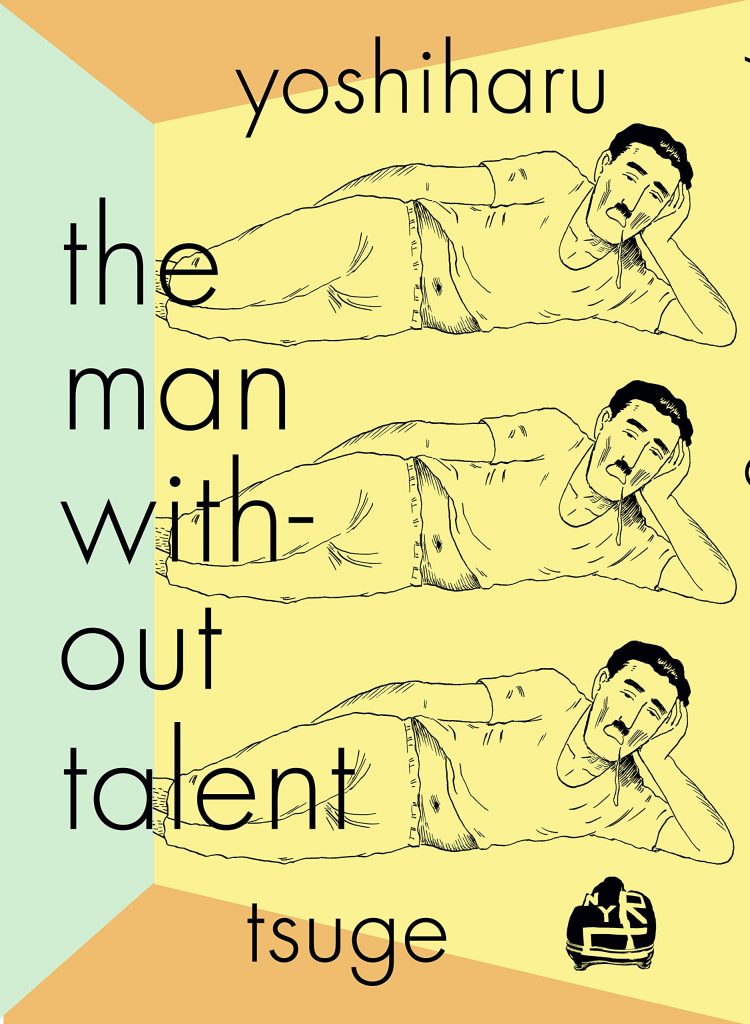

The Man Without Talent is a remarkable work, and considering it was issued in 1986, that it’s taken over thirty years for an English translation is also astonishing. Despite a distancing alias it presents as autobiography, but such is the carefully cultivated surreal tone there’s often the feeling of reading an elaborate hoax purporting to be autobiography. The reverential pomposity of translator Ryan Holmberg’s back of the book essay further feeds that suggestion.

Yoshiharu Tsuge’s individuality straddles a form of reality and the shaggy dog-like nature of a dream as he spotlights his stand-in Sukezō Sukegawa, a dispirited former comic artist fallen on hard times, possibly of his own making. As an alternative method of providing for his family he conceives a plan to re-open a closed river crossing, intending to raise the money for restoration by gathering stones from the river and selling them to collectors. To the despair of his wife, this introduces Sukezō to a world of scruffy losers perpetuating a dying hobby, while he persists in attempting to sell them from a shabby tented stand near the river itself. It’s just the first in a succession of decisions minor and major that make you question what planet Sukezō inhabits, yet as this is autobiographical exaggeration there are elements of truth, and therefore of self-awareness.

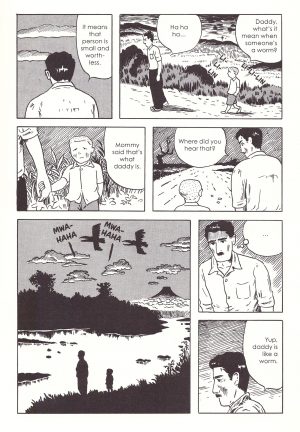

Throughout the six chapters a constant feeling of sympathy is generated. It’s intentional as Sukezō’s infant son is pictured coming to collect him at night and struggling to cope with his father’s obsessions, and to a lesser extent presented for his exasperated and long-suffering wife. Sympathy for Sukezō/Tsuge is more conflicted, dependent on how much of himself is actually invested in Sukezō. He’s by turns cynical, self-destructive and self-obsessed, refusing the one career that would earn money in favour of pie in the sky ideas, and any idea of personal dignity has long evaporated. It’s not mentioned in-story, nor suggested in Holmberg’s essay, but many readers will consider mental illness, possibly depression. While living in a very different world to English language readers, the pressures of modern life are apparent in not just Sukezō’s existence, but those on whom he models himself, eventually landing on poet Seigetsu Inoue, already disconnected from 19th century life.

A distanced mood is created by Tsuge’s very precise and delicate illustrations, offering no more than necessary wherever A Man Without Talent weaves, yet obviously belying the title as there’s a great beauty to some panels.

There is no definitive outcome, as Tsuge closes on Inoue’s dissolute life having already offered his thoughts on his own existence. Does he consider he’s following the same path, or does he just connect with similar artistic torment? It’s one of the many ambiguities and unanswered questions Tsuge raises. Why is Sukezō’s wife drawn with her face constantly hidden over the first chapters? Is this a metaphor for not wanting to hear what she has to say as it flies in the face of his fantasies? Just what is the allure of other unhappy and unfulfilled lives?

Holmberg’s essay reveals that in Japan there are those who consider Tsuge a sage. His views were published at the peak of Japan’s decades long boom in 1986, questioning the validity of the society it developed. When the boom became bust there was a natural inclination to look outside the bubble, and by then a movie adaptation had been filmed. Whether presenting sage, wastrel or depressive, The Man Without Talent is haunting and memorable.