Review by Ian Keogh

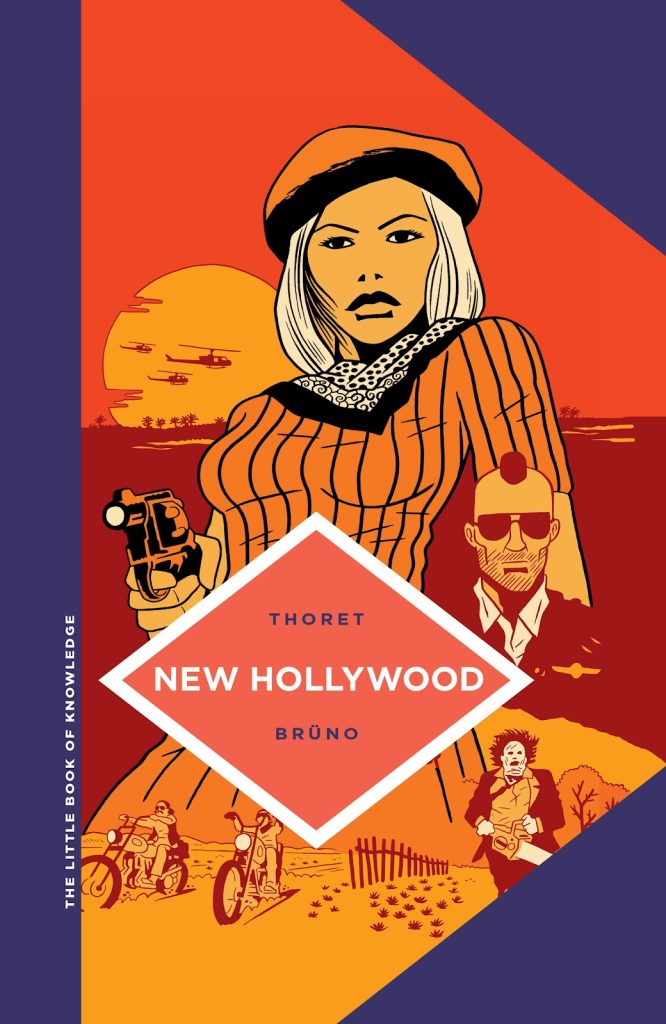

The term ‘New Hollywood’ is applied by cinema critics and enthusiasts to the 1970s films of then new directors whose careers began with a modern viewpoint rejecting dying, decades old cinematic approaches. There’s some discussion as to the beginning and the end of the New Hollywood period, but French film critic Jean-Baptiste Thoret’s choice is to begin in 1969 with the release of Easy Rider and end a decade later when Apocalypse Now arrived. His viewing list, though, includes both earlier and later films, as does his text.

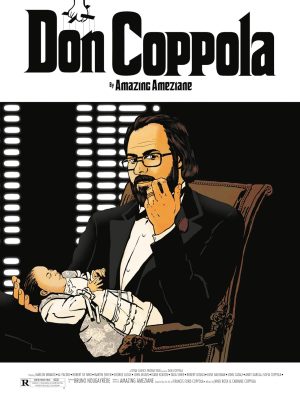

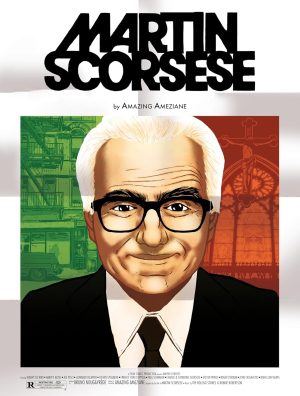

That Thoret’s view deviates from the conventional is exemplified by his devoting two pages to Henry Zapruder’s self-shot film of John F. Kennedy’s assassination as a cornerstone influence on the American cinema that followed. It’s surprising, but Thoret constantly surprises, both with his individuality and his insight, and there’s no false snobbery about him. He’s as willing to talk about the influence of Roger Corman as he is to discuss Martin Scorsese, and there’s no sidelining of Black film directors, often forgotten when the likes of Altman, Coppola and Lucas are discussed.

The films under the spotlight are contextualised as part of the times they either rebelled against or the influences absorbed from them. Year by year Thoret takes us through the 1970s offering an honest appraisal. While many of the films spotlighted were major commercial successes, many more were playing only to a small foresighted audience who accepted change, and it was a long time before critical appreciation manifested. Thoret also weaves together an extraordinary diversity of styles and approaches, along with the outside factors that came into play. The Godfather’s status, for instance, was cemented at the time by dispensing with traditional methods of releasing a film by allowing audiences throughout the USA to see it simultaneously, and the knock-on effect that had.

In one sense artist Brüno (Thielleux) could have had an easy assignment just copying movie stills and pictures of the quoted directors, but he goes the extra mile, creating montages and giving the directors interesting surroundings related to their films. Joe Dante is seated in a cinema surrounded by gremlins. As an expressionistic cartoonist Brüno doesn’t deliver exact likenesses, but in context there’s no mistaking who people are.

New Hollywood is designed as a lecture, with several sequences showing Thoret delivering it on a drive-in cinema screen, and covers an immense amount of ground in relatively few pages. It’s erudite and informed, but Thoret would surely only consider it a ground-covering primer for further investigation.