Review by Frank Plowright

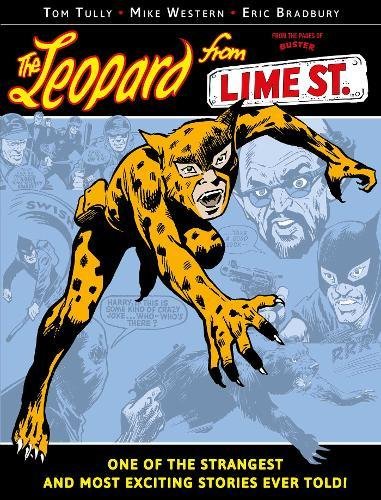

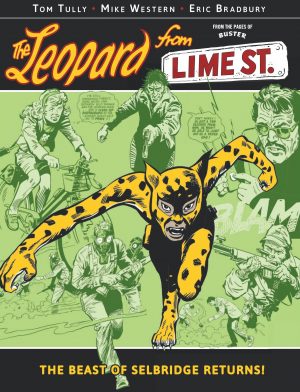

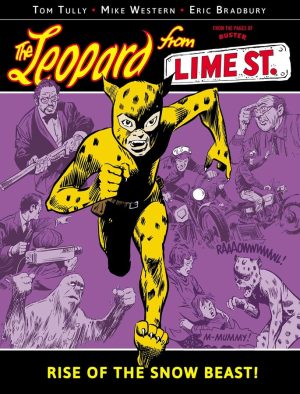

Rebellion can’t say so, but the starting point for The Leopard From Lime St was Tom Tully’s pastiche of Spider-Man. Plucky smart kid Billy Farmer is clawed by a leopard being treated with an experimental radioactive serum and almost immediately finds himself with leopard-like powers of enhanced speed, strength and agility along with some super senses. Luckily there’s an old Dick Whittington’s cat pantomime costume in his wardrobe, and Billy makes the immediate decision to fight crime. Even more luckily, he has his camera with him, so he can take pictures and sell them to the tyrannical Thaddeus Clegg at the Selbridge gazette. Billy’s also orphaned, but there’s no kindly old Uncle Ben looking after him. Billy’s saddled with the brutal Uncle Charlie, wife beater, and quick to take the belt to his nephew and his money from him.

Started in 1975, and serialised in three page episodes, Tully’s scripts are primarily adventure with a few comedy elements thrown in, Tully good at keeping the thrills coming while maintaining a knowing wink at the audience. Like all continued strips, there’s a settling in period and Billy has a few costumed adventures by the time Tully lets his imagination fly a little. As well as using his powers to confound Uncle Charlie and rescue kidnapped TV actresses, Billy has no compunctions about using them for personal gain, but only on a small scale.

Mike Western and Eric Bradbury combined for the art, Western handling the layouts while Bradbury finished the art, a very unusual combination for British comics of the era, where artists more usually pencilled and inked a strip. Just as Tully was simultaneously writing several other weekly strips, the artists were also drawing other material. The result of their collaboration is a tidy looseness with considerable detail, and an impressive ten panels packed onto a page. A strength is character design, with each of the prominent cast distinctive.

It wasn’t intended as such, but The Leopard From Lime St presents a convincing historical document, not least a nasty window into what was considered socially acceptable at the time. Yes, Tully’s scripts are exaggerated for comedic effect, but you wouldn’t see Uncle Charlie in today’s comics without a tag around his ankle. Billy motivated by saving up for a colour television is charmingly dated touch, and this is an era when the circus still came to town and paraded down the high street.

Such is the amount of filching from Spider-Man there’s a fear that when the Leopard challenges a masked wrestler his kindly Aunty Joan will cop it from a burglar on the way back from stealing the show receipts. However, instead of the glamour of New York providing the background, it’s the British provincial town of Selbridge, which recontextualises the common elements effectively. As the strip continues Tully slips more into Superman territory with Billy having to protect his other identity from assorted suspicious snoopers, but there’s enough variation to prevent repetition.

There’s a charm and a craft to The Leopard From Lime Street, but this collection is aimed squarely at people who remember it fondly from their youth as it’s unlikely seven to twelve year olds of the 21st century would find much in common with Billy.