Review by Frank Plowright

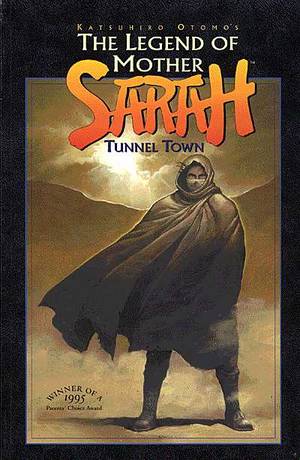

Katsuhiro Ōtomo spent eight years writing, drawing and animating Akira, a landmark in terms of popularising Japanese comics beyond their home shores. Perhaps mindful of how long Akira had taken, Otomo restricted himself to writing his next project, leaving the art to Takumi Nagayasu. Between them they created a tighter story that in some ways surpasses Akira by virtue of maintaining the focus, yet it’s slipped into undeserved obscurity.

The setting is an Earth in the near future. Humanity deserts a planet rendered largely uninhabitable by nuclear holocaust, then ecological zealots activate a device that tilts Earth’s axis, resulting in devastating climate alteration. As two political poles battled for control many evacuees deserted the space stations that had been their refuge and returned to a harsh planet under military rule. Separated from her three children, Sarah wanders from isolated community to isolated community searching for them. She is however, no ordinary mother. A resourceful former political activist, her priorities have now shifted, but the life skills remain.

It’s very much in the tradition of the Japanese ronin stories or a Clint Eastwood Western, a simple story stylishly told, with the stranger in town setting events in motion that change everyone’s lives. The original comic serialisation was apparently not as successful as hoped, and word generated from that impacted on the collection. It’s understandable that fans attracted by the science fiction action dazzle of Akira would possibly not be inclined to venture further than a first chapter in which Sarah arrives in a mining town accompanied by Tsue, a wily cross-eyed trader. Japanese readers would be used to this leisurely style of introduction, and given the way the remainder of the story plays out, it’s well considered.

The mines are under military control, use slave labour and hold a secret. Sarah befriends a teenage girl called Lucia, in love with a young soldier, Toki. He’s brilliantly realised, conflicted by ambition, loyalty and a nature fundamentally unsuited to military life. The discovery in the mines unleashes the worst in most of the cast, all gradually embroiled in a tense affair with an absolutely stunning extended conclusion. It’s a bleak parable of human nature, but a compelling read.

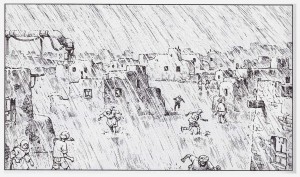

Anyone concerned about the art should be informed that Nagayasu effortlessly apes Ōtomo’s style, possibly because as a former assistant he contributed heavily to that style. There’s the same delicacy of line and effective layouts, and he doesn’t shy away from the extended detailed scenes that do little more than prompt a cinematic mood.

Dark Horse persisted with Mother Sarah, serialising ‘City of Angels‘ and ‘City of Children‘, but never publishing collections. Anyone enjoying this is advised to investigate further.