Review by Ian Keogh

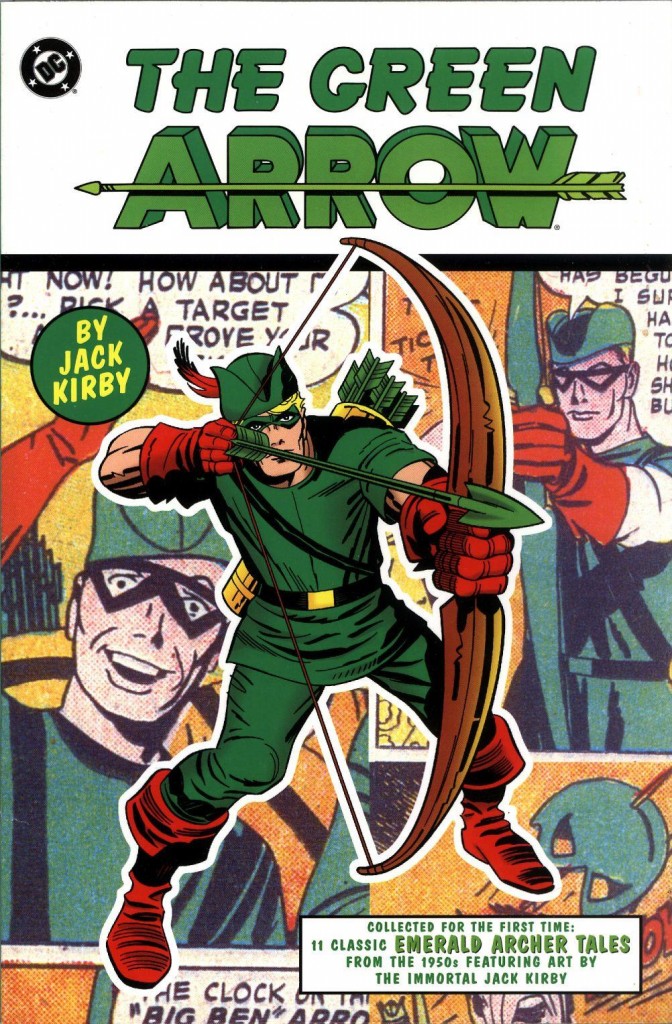

Comics has never seen anything like Jack Kirby and it’s unlikely that his individual combination of prodigious imagination, dymanic draftsmanship and incredible work rate will ever be matched. That’s not to say, however, that everything he created was pure gold. A zest for experimentation inevitably produces duds along the way, and there were times during his career that Kirby’s priority was to pay the mortgage. The back cover blurb collecting his 1958 work on Green Arrow admits as much. He took the strips and he drew them. He drew them well, but the introduction by Roz Kirby reveals there was no great enthusiasm.

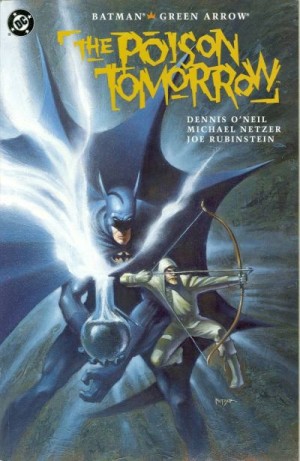

Created by Mort Weisinger, Green Arrow’s only real difference from the gimmick-led Batman feature of the era was use of a bow and arrow. Otherwise he was a millionaire masked detective with a sidekick, a specialised car and plane, and his own hideaway festooned with trophies and souvenirs. It was a formula successful enough to ensure Green Arrow rode out the early 1950s drop in popularity for superheroes, but never enough to boost him beyond a decade of short strips in anthology titles.

Kirby identified that Green Arrow required a new approach to elevate his stature, settling on science fiction, but as explained in the editorial, Weisinger, by then an important man at DC, railed against this reinterpretation of his creation, and the idea was dropped. It meant that the main attraction of Green Arrow’s feature remained the ever-preposterous selection of trick arrows defying any logic. A ‘rain’ arrow is a water sprinkling shower head, a fountain pen arrow attaches to a car and leaves an ink trail and firecracker arrows are particular favourites. It could be said that these are fantasy strips, and a suspension of disbelief should be applied, but these gimmicks were inserted into logic-based detection plots. More relevant is these being strips intended as rapid passing entertainment for children, not works to be analysed decades later.

Just how much Kirby was jazzing up the plots he was supplied with is unknown. His wife’s introduction notes he was given free rein to improve the scripts supplied by Robert Bernstein, Bill Finger, Ed Herron and Dave Wood, and given what remained, improvement was certainly required. It would be nice to report that Kirby’s art dragged this genre material into something special, but it doesn’t. It’s always professional, and there is the occasional inspired page – Kirby appeared unusually enthused about a strip with a giant mechanical octopus – but this was work for hire.

The one exception to the above is the penultimate strip in which Herron and Kirby completely redefine Green Arrow’s origin, creating the version that’s survived with modification and additions ever since. Oliver Queen is stranded on a desert island, and develops his prodigious bow and arrow techniques as survival skills. This is the only strip not reliant on trickery or contrived detection, and the best in the book. The nadir is Wood’s opening strip in which those Green Arrow has inspired in other lands all turn up in the USA for a contest.

This affordable collection supplies otherwise long out of print material by one of the greats, but it’s not the material for which he’ll be remembered. Those who really want to read it might instead try The Jack Kirby Omnibus Volume One, where the Green Arrow stories are collected along with a selection of other material Kirby contributed to DC’s anthology comics in the 1950s.