Review by Graham Johnstone

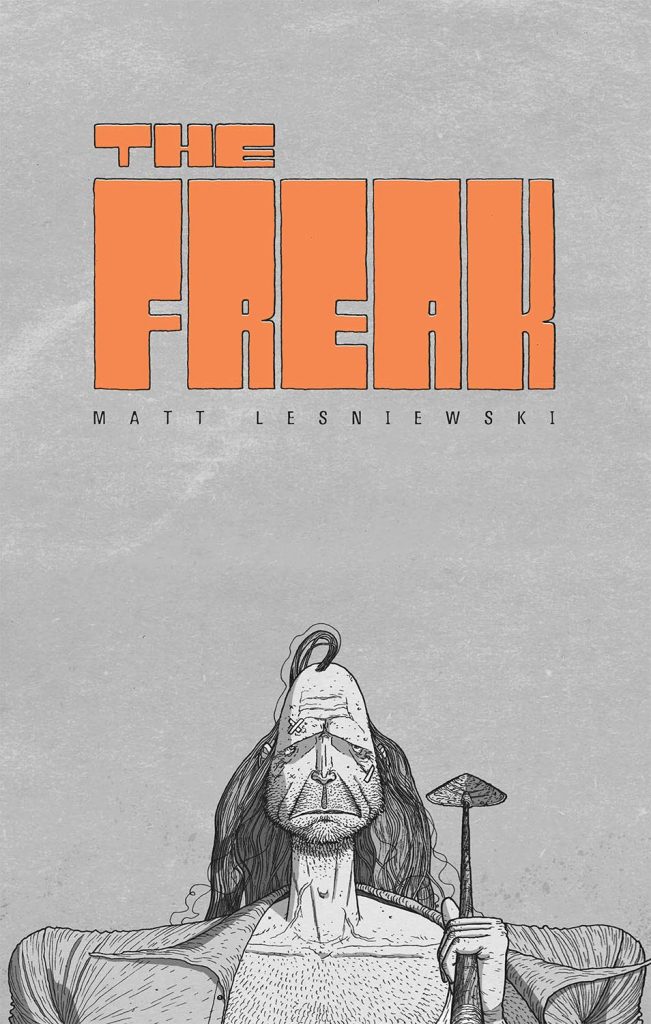

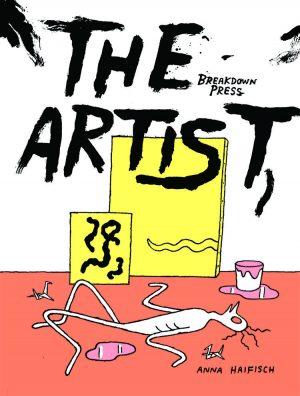

The Freak, is the début graphic novel from Matt Lesniewski. His self-published one-shot impressed boutique publisher AdHouse Books, who commissioned him to expand it.

The cover-featured and nameless ‘Freak’, grew up in a small community, where he was vilified and attacked for his appearance, fuelling a cycle of self-isolation and rejection. His only opportunity was grave digging, making his only ‘community’ the dead. He decides that in a city he will be insignificant enough to be left alone, and sets off with his shovel, so initiating a ‘stranger arrives in town’ plot. It’s a timeless scenario, suggesting a folk tale, with the narration further making it sound like a well-rehearsed story, told round a camp fire.

The Freak and his shovel find the city no more welcoming, and the loss of the shovel triggers an escalation. By the end of the first chapter, he’s gone from unwelcome refugee to fugitive. Chapter two sees him tailed by two figures who’ve seen his wanted poster, and ends with an unexpected and charming reveal. The third and final chapter sees him struggle to adapt to new circumstances, and reach a decision about his future. The dramatic question is whether the Freak can leave behind his past, or is he still compelled to act it out?

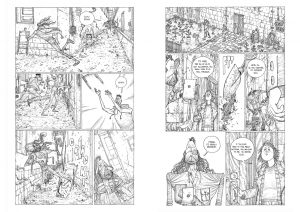

Lesniewski is an impressive artist. Evidently inspired by Moebius, he avoids the latter’s occasionally dry tonal hatching, instead making every line and dot artfully convey form and texture. The lack of colour or spot blacks occasionally makes images require a moment to emerge from the elegant lines, but that’s a minor issue. His later work with colourists gains in immediate clarity, but obscures his line work. Lesniewski’s story plays to his visual strengths: the unspecified time and place is vividly realised, with distinctive sets, and costumes that are convincing down to details like the Police uniforms’ zippered bumbags. Character design is excellent, with the protagonist’s freakish elongation mirrored by his shovel, and his charmingly gangly movements highlighted in some spectacular chase sequences (pictured, left).

This is a strong story, though imperfectly told. There’s no last straw, or inciting incident, that makes the Freak leave home, and the reaction to his arrival in the city seems too instantaneous, and consequently unconvincing. Similarly, he finds his precious lost shovel too soon, with no indication of a search. The shovel’s totemic importance is clear, yet the Freak’s reaction still seems disproportionate. This changes his position from unjustly vilified outsider to justly hunted criminal, so undermining reader sympathy. Other key events are fudged. For example, over multiple pages of the Freak being tailed, Lesniewski doesn’t show him spotting his pursuers – there’s no reflection in a window, or glance over a shoulder, making it odd that he would discard his precious sandwich to flee. Further elements of the following confrontation don’t convince, like how an apparent pursuer appears ahead of him, or what (despite an inset panel focussed on a detail) finally downs the Freak. However, a transition into a dream sequence is deftly handled. The story is also heavily narrated, carrying the load of the Freak’s reactions and decisions, not always conveyed in the visuals or minimal dialogue.

Such occasional storytelling inexactitude doesn’t stop The Freak reading as a powerful fable, with underlying psychological and social truths about isolation, exclusion, and the persistent effects of trauma. However, it’s a modern fable, with an ambivalent ending, instead of the traditional moral lesson. The art impresses throughout, with The Freak also a promising debut for Lesniewski as a writer, and reason to look forward to future books.