Review by Win Wiacek

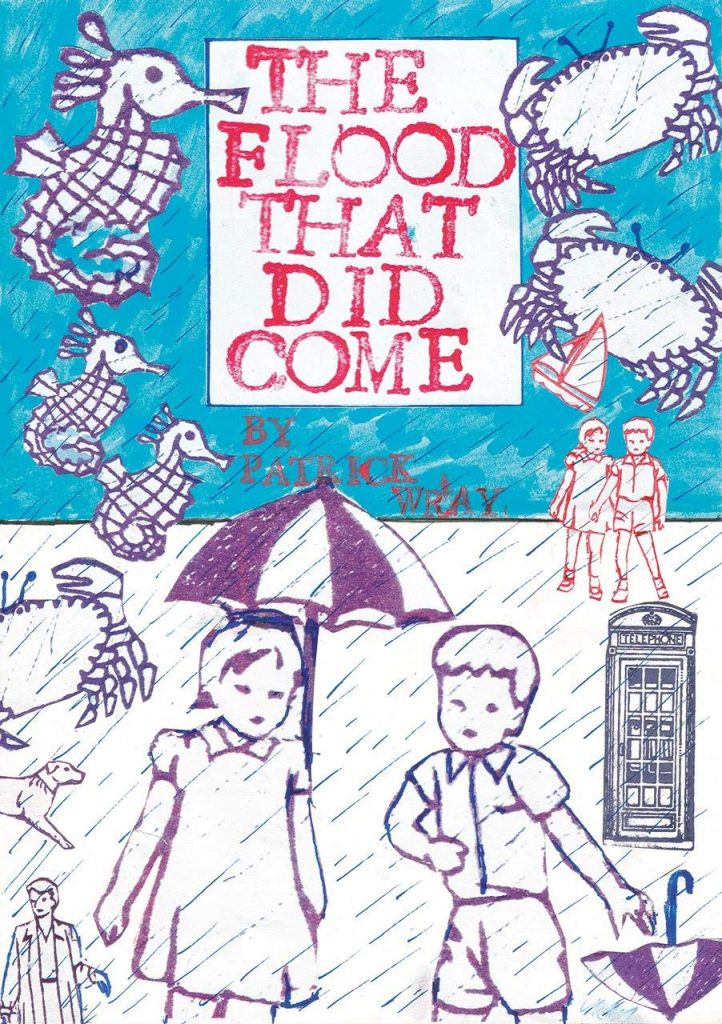

The UK has a proud tradition of using fiction and fantasy, especially those presented in the aspects of children’s books, to hold up a light to political and social dystopias. It works for Gulliver’s Travels and Animal Farm and dozens of comics and graphic novels. Patrick Wray’s The Flood That Did Come is one more and it’s supremely, chillingly good at what it does.

Wray is an artist, writer and musician who studied at Dartington College of Art and took a long time living before crafting this telling and subtle exploration of property laws and the role of the people in how they’re governed. Mimicking the narrative tone of children’s reading primers (and many kids’ comics) The Flood That Did Come is set in the hilltop village of Pennyworth in the year 2036. It’s all the home little Jenny and her brother Tom know, but their happy innocent days end when it starts to rain heavily… and never stops. Soon, all of Kingsby County and the entire country are under water, with only a few high-lying hamlets remaining above water.

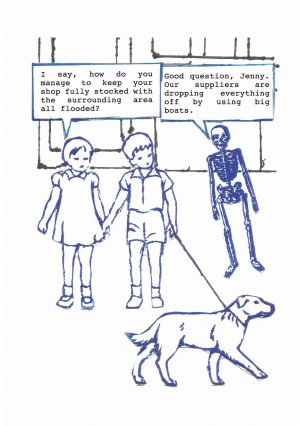

The kids and their friends make the best of the new normal and enjoy the changes to the wildlife around them, leaving the adults to worry about the details such as being resupplied by airdrops. One day, however, the holiday ends when a sailing boat arrives from nearby industrialised town Brooks Falls. The children aboard have come to warn the Pennyworth residents that the adults of their drowned conurbation are coming, armed with the latest technologies and the law. It transpires that long ago back in 1851, Pennyworth was merely an outlying district of the metropolis and still remains part of the greater whole. Now that it’s the only part above water, the Mayor and council of Brook Falls intend to move their operation here and carry on their business as usual. Sadly, as always when politicians and big business want something, the rights and feelings of ordinary people don’t count for much.

Simple, breezy and chilling to the core, this tale of resistance and capitulation is made all the more effective by Wray’s cunning choice of art style and faux children’s book feel. The result is reminiscent of school workshops and protest marches supplied with stencil screens; of street-rebel print slogans and tagging-inspired found imagery. The industrial-flavoured visuals magnificently disguise the potency of the political allegory and make this a tale no tuned-in, socially aware grown up will want to miss.