Review by Cefn Ridout

What is the fate of the artist in modern society? Eddie Campbell gamely tackles the issue by offering up his own life for scrutiny in The Fate of the Artist and suffers the inevitable consequences.

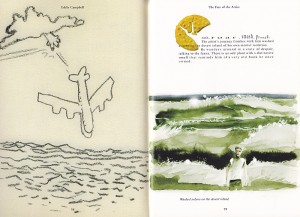

In the early 1980s, Eddie Campbell’s ‘Alec’ tales were a revelation. His wry, understated and poetic recollections of life and love down by Southend-on-Sea effortlessly captured the wayward rhythms of real life through finely-tuned conversational dialogue, impressionistic visuals and leisurely, discursive yarn spinning.

In later semi-autobiographical forays, the wistful, antic verve of Campbell’s earlier work gives way to a more rueful humour as the realities of middle age, providing for his family and self-publishing permeate his comic universe. In The Fate of the Artist, Campbell’s paper-thin alter ego, Alec McGarry, has been consigned to history, enabling the creator to take centre stage – but not for long.

The legendary Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn once jibed: “I don’t think anyone should write their autobiography until after they’re dead.” At the risk of disclosing a fairly predictable turn of events in The Fate of the Artist, Campbell takes the legendary Goldwyn’s bon mot to heart. Foretitled “His Domestic Apocalypse”, this posthumous, post-modern memoir finds Campbell conducting an investigation into his own sudden disappearance.

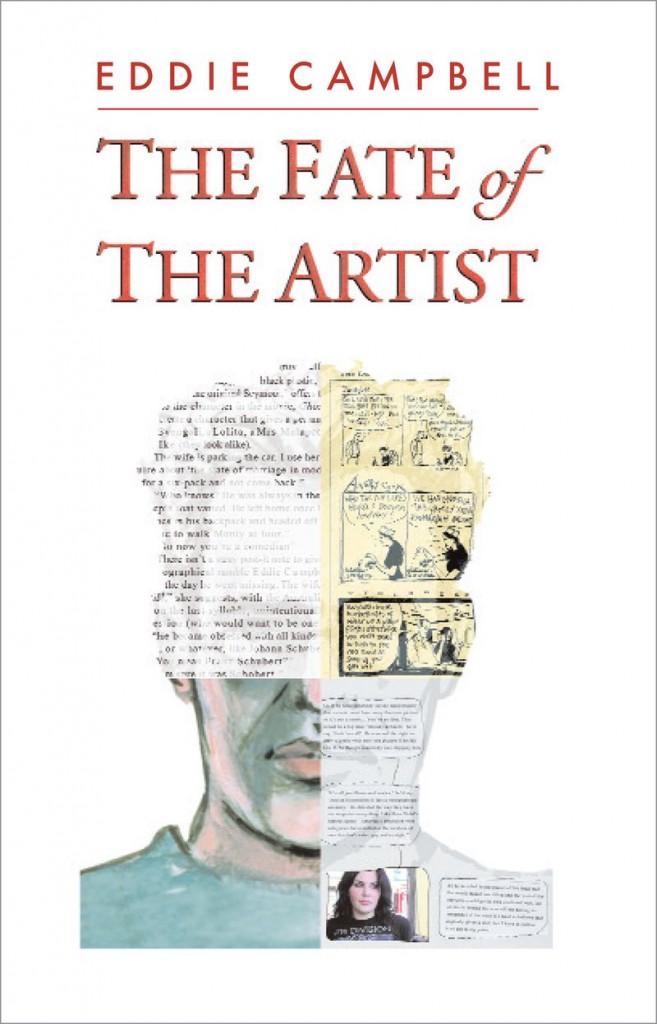

In a departure from his previous work, Campbell deftly dovetails four narrative strands, each told from a different viewpoint and visualised in a distinctive style, to create a complex portrait of an artist who has lost faith in his art, himself and his readers. The central theatrical conceit is foreshadowed on the covers, the front depicting a self-portrait assembled from four artistic modes – prose, cartoon strips, fumetti and full-colour painting, with the back cover revealing the image as a flimsily constructed façade.

In the principal painted sequence of this elaborate play an actor takes the role of Eddie Campbell, while a detective quizzes Campbell’s family about his last movements and state of mind in typographically tricked-out prose. These strands are intercut with a fake fumetti-like interview with Campbell’s teenage daughter Hayley, who berates her father about his increasingly self-obsessed, aberrant behaviour, and a barbed parody of a vintage gag strip, ala Blondie and Dagwood, charting the collapse of a marriage from suburban bliss to domestic violence.

Upon discovering his fate filed under the Dewey decimal system’s new category for graphic novels, our dear departed hero learns that the secret of existence is just a cut ‘n’ paste cosmic joke. And the book’s coda, a Classics Illustrated style dramatisation of O. Henry’s short story ‘The Confessions of a Humorist’, underscores the perils of exploiting family and friends in the service of art.

On first reading it’s easy to become entangled in Campbell’s ambitious, multi-threaded storytelling and emerge with little more than a sense of the book’s graphic novelty and wonder if Campbell has lost the plot as he airs his grievances in public. However, The Fate of the Artist rewards subsequent readings. The pieces of the puzzle fall more clearly into place and the switching narratives feel like key changes in a longer composition, throwing into sharper relief Campbell’s genuine insights into the difficulties of reconciling real life with a creative calling. It ranks close to his essential best: The King Canute Crowd and Graffiti Kitchen.

The Fate of the Artist also harnesses the intrinsic strengths of the comic strip language. As such, Campbell, who has long believed that the “graphic novel signifies a movement rather than a form”, has crafted a clever riposte to the self-appointed “definers” and “graphic novel police” who would issue him with an infringement notice for not playing by the rules.