Review by Karl Verhoven

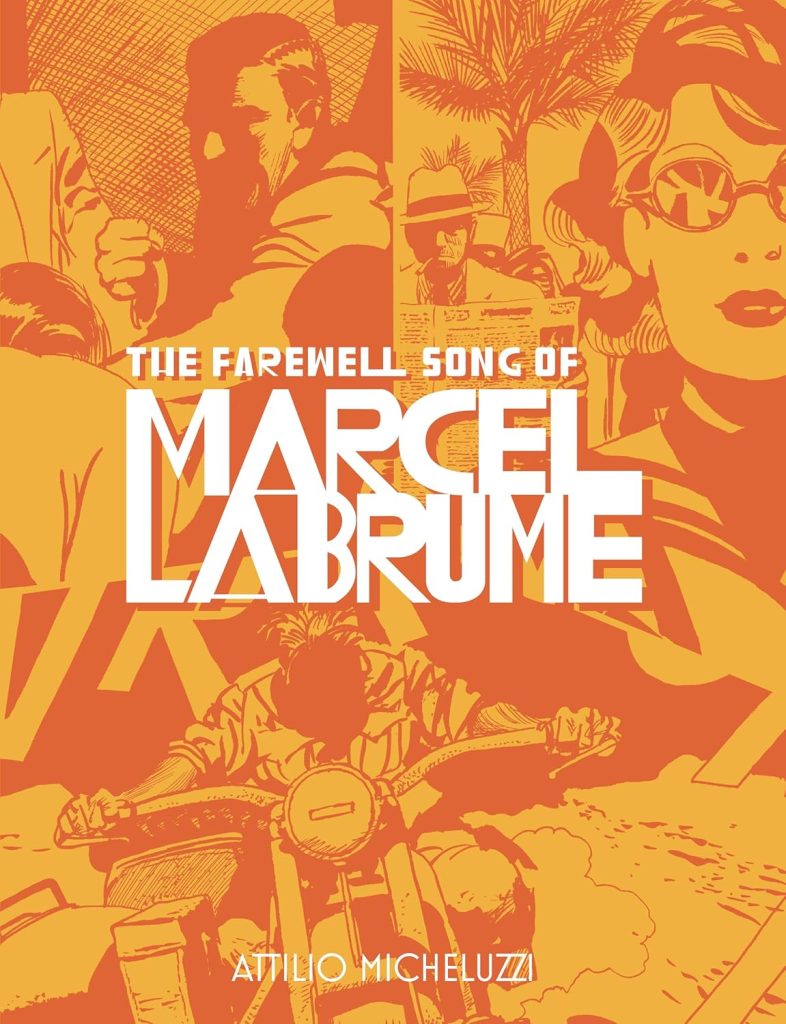

Attilio Micheluzzi is yet another phenomenal artist whose work is revered throughout Europe, having packed a lot into a relatively brief sixteen year career. However, he remains a secret to most English speaking comic fans. Thankfully, Fantagraphics Books aim to put that right, and The Farewell Song of Marcel Labrume is the first of a proposed complete English library of his works. It combines two stories completed between 1981 and 1983 starring French journalist Marcel Labrume.

Both slide into the European tradition of historical adventure, being set in Lebanon during World War II, yet Micheluzzi’s influences are American cinema and American newspaper strips. At times the opening story seems nothing so much as an elaborate homage to Casablanca drawn in the style of Milton Caniff. It lacks the kinetic imperative found in Canniff’s art, but the characters and the shading bring him to mind. The cast is extremely identifiable. The ice cool blonde American woman Carole Gibson is supernaturally poised and attractive, and the distinctively slimy Guillaumet contrasts gaunt Jewish refugee Montafiore Spirakowski. Micheluzzi’s greatest artistic strength, though, is creating a sense of place, and that’s all his own. The immaculately defined locations are as involving as the personalities.

The melting pot cast are gathered in Beirut, in March 1940 under the control of the French, whose home nation still hadn’t been overrun by Germany. However, as the year progresses that changes, and so does the political climate in Beirut. The central character and narrative voice is Labrume, self-interested observer whose allegiances are never clear, marking him as the product of another influence, Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese. Labrume features in a plot too complex for its own good, involving too many people seemingly adjusted according to what Micheluzzi wanted to draw at any particular time. It does all hang together, but may need a second reading to verify that. Still, with art so good, is that any hardship?

‘In Search of Lost Time’ is more straightforward, with any lack of cohesion due to it being true to what Labrume knows or feels, and as he’s recovering from being caught in a bombing he isn’t fully functioning. Besides which, he’s no paragon of virtue, a protagonist, not a hero. His homing instinct is strong, so he escapes from a German hospital and rapidly finds himself accompanying five British women. “Implausible. The whole story’s implausible”, he thinks to himself, perhaps echoing the reader, “but who said that reality can be stranger than fiction? Tell me, I want to find him and look him in the eye. Because it’s true”. Hmmm.

Naval warfare eventually manifests, and Micheluzzi’s painstaking methods are gorgeously applied to boats, planes and submarines, the black and white detail bringing to mind the better British war stories of the type Pratt once worked on. It’s emotionally stronger than the first story, as Labrume eventually develops some feelings. However, historical detail is again dropped assuming readers will be familiar with who allied with whom and where during the 1940s, and the outcomes of individual battles. A text article in the back offers some explanations, but it greatly slows the reading attempting to figure out what’s being discussed and why it’s relevant.

The art shines, and is worth the price of the book alone, but could the series not have begun with a work not so dependent on historical detail?