Review by Ian Keogh

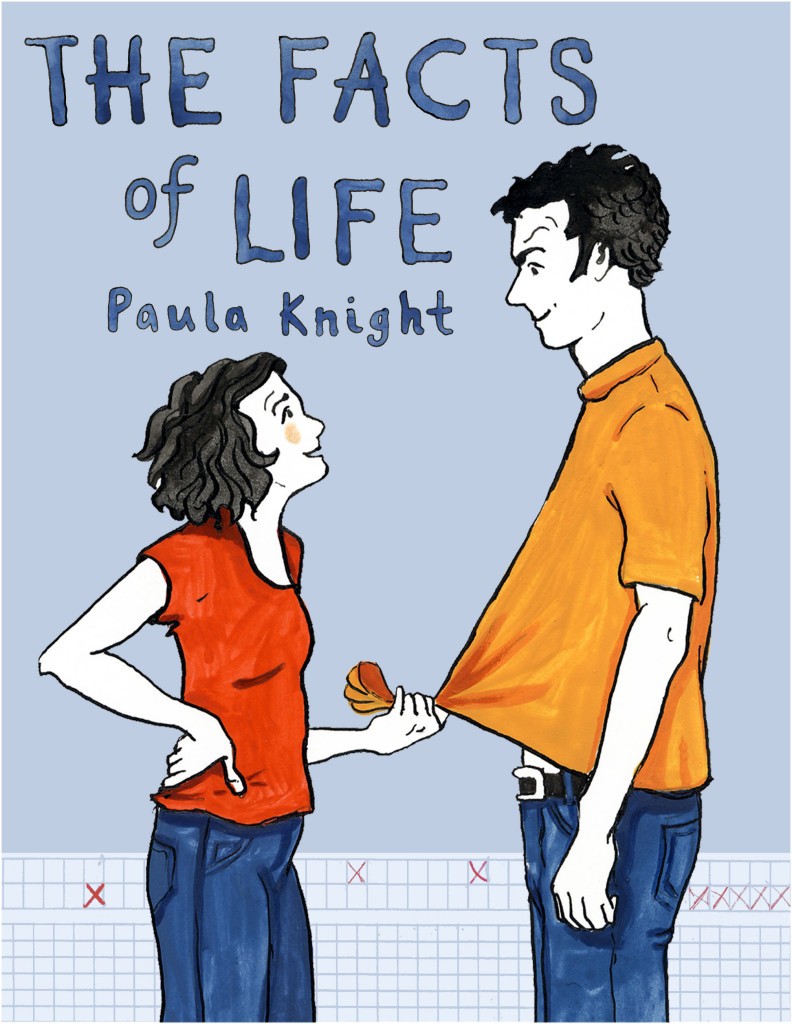

The first quarter of The Facts of Life passes pleasantly enough as Paula Knight, or more precisely her stand-in Polly grows up in 1970s and 1980s Britain. She’s the exclusive focus, but her existence hardly differs from that experienced by millions of others. It passes the time, it’s charmingly drawn, but there’s nothing individual indicating why anyone would spend money to read it.

That comes into focus around page sixty when there’s the first mention of Polly’s lack of commitment to the idea of having children. It’s part of a discussion with her strong-minded nan, who has further fixed views about the roles of women. Thereafter an illness over many years restricts Polly’s social and employment possibilities and we read of her feeling of somehow being left behind as friends follow prescribed life structures. This, though, is just an observation rather than any great yearning to have children, about which she remains ambivalent. It’s an attitude that only begins to shift approaching the age where conception and pregnancy become increasingly more difficult.

As The Facts of Life continues Polly’s experiences open the door into a secret world that’s new territory for the graphic novel memoir. The same matter of fact approach characterising the early stages of the book is applied to procedures and disclosures regarding childbirth that all too many of us have been conditioned to believe as private matters, concerns not be discussed in public. Whether intentional or a secondary effect, there’s a wealth of amiable and concise advice lacking in clinical books. As in the early stages of the book, what’s happening is extremely common, yet barely aired in public, and these are a catalogue of emotional and physical uncertainties for which no-one can be prepared. In the UK at least an understanding physician is vital, particularly with regard to chronic fatigue syndrome (or ME), a condition dismissed for several decades by the medical profession.

Polly’s life is further blighted by recurring miscarriages, with all the accompanying emotional upheaval. There’s a particularly effective sequence contrasting Polly’s upset at it occurring again with a teenage girl blithely heading in for an abortion that’s a lesser concern to her than the top she’s going to buy when she leaves hospital. Such pithy observations characterise Knight’s work, visual as well as verbal, a later page equating the Bristol channel with female reproductive organs. Other emotional considerations that only occur in specific circumstances include the destiny of family heirlooms for childless couples, or the founding of a commune for older people. Is this book to be the repository of family anecdotes for posterity?

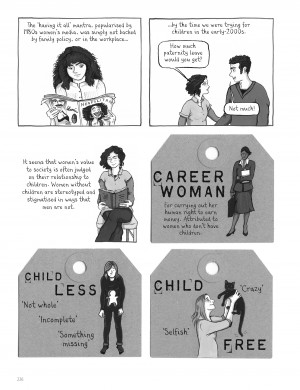

The final section investigates commonplace attitudes toward anyone who doesn’t have children, and how this came about. This is the one point where the narrative appears to hit a speedbump, as it doesn’t acknowledge many of those with children are aware of how fulfilling life can be without, yet a different fulfilment occurs with. Patronising, awkward and unhelpful comments indicate societal presumption, yet the argument made is that this is entirely without solid foundation and based more on socio-economic grounds.

A moving honesty and sympathetic insight runs through The Facts of Life, whether childbirth (or not) is the topic under the spotlight, or a broader range of personal issues. It might be assumed this is a book with greater appeal for women, but we share the planet, and most men beyond their teens would greatly benefit from reading this memoir.