Review by Ian Keogh

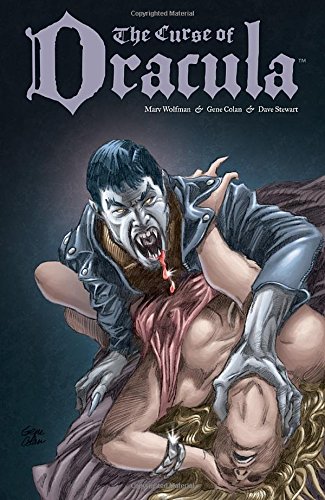

Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan are jointly responsible for the definitive version of Dracula in comics with their highly acclaimed Tomb of Dracula series during the 1970s. Wolfman’s introduction relates that it took him some while to conclude his original concept of Dracula and his world wasn’t the only possible definition, and when offered the opportunity to work with Colan again his approach differed. The expectations engendered by the creative team and their previous work led to a less than enthusiastic reception for The Curse of Dracula when originally serialised.

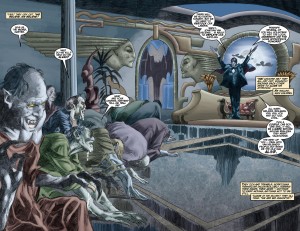

That’s possibly because despite Wolfman’s introduction noting the differences in the supporting cast, they’re not very far removed from the cast he created for the Tomb of Dracula series. In fact, it’s as if many of their characteristics and genders have merely been shuffled. This van Helsing is male and has his vocal chords severed rather than being scarred. There’s a proactive wooden bolt-firing Japanese vampire hunter, but she’s female and blind, and the other foreign team member is Russian, not Indian. Over three chapters there’s little time for the differences to seep through.

Reconstructing Dracula and his vampire mythology away from Marvel permits more explicit horror, and it’s odd to see the usually restrained Colan illustrating this. His art is his usual tight, elegantly illustrative and flowing pencil work, but it’s not inked, instead embellished in the colouring process by Dave Stewart.

Given the creative team, the major difference is the interpretation of Dracula himself. He’s been redesigned by Colan and now lacks an old world nobility. He’s more openly covetous and willing to abuse those in his thrall. His objective is political power, albeit one stage removed as the power behind the throne, and he’s far less concerned about keeping his capabilities secret. An awful lot of people in this San Francisco are aware of him.

Attempting to discard all comparisons with the former series, we’re left with a relatively rushed plot that required more space to breathe and to introduce a cast who’re defined by their nationalities and disabilities rather than any lingering personaility. It’s backed up with reproductions of Colan’s original pencil work and some other sketches, but never reaches its potential.