Review by Ian Keogh

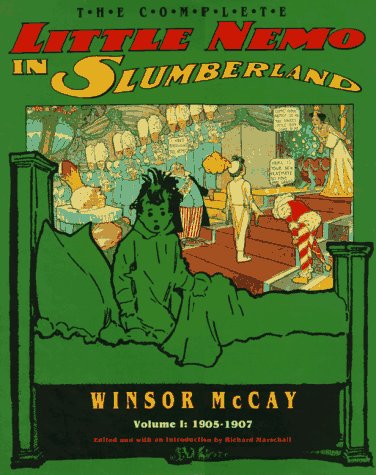

Over a century since its introduction, Little Nemo in Slumberland remains a masterpiece of the comic form. Consistently imaginative, beautifully drawn, and insanely decorative, the strip has never been bettered. It’s available in several formats, and for those unable to afford the luxury of the Taschen collection reprinting the complete series at its original broadsheet size, the best bet is the six volumes of this late 1980s and early 1990s hardcover reprint co-published by Fantagraphics Books and Titan Books. Each of the almost 100 page collections features full colour reproduction that will be acceptable to all but the most demanding of buyers, along with an erudite introduction from newspaper strip historian Richard Marschall. The printed size of 13.8 inches by 10.5 inches is roughly half that of the original folded newspaper inserts, but it’s more than good enough to appreciate the delicacy and vibrancy of Winsor McCay’s work.

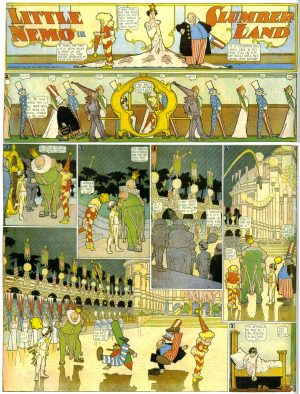

A young boy, around ten years old, dreams vividly of a magic kingdom, where the only boundaries are the limits of his imagination. He travels there every night, and ends every strip awakened in bed, comforted by a parent if his dream has been particularly stressful. McCay was a both pioneer and innovator, Little Nemo manifesting only a decade into the lifespan of the US comic strip, when newspaper publication was the sole venue, and it’s surely not possible to overstate his importance and his innovations. Already an accomplished illustrator when he began the strip, McKay rapidly understood the possibilities of the form and his large format presentation. In only his second strip he’s already experimenting with the use of long vertical panels as Nemo sinks through his bed into a forest of tall and crumbling mushrooms. That is an exception rather than an establishment of form as almost all the remaining strips from 1905 employ a more conventional left to right panel structure with unnecessary descriptive text beneath each panel. That was editorial insistence, the belief being the public needed the text as they couldn’t follow illustrations and word balloons alone. By early 1906 McCay had won that disagreement, and the text vanishes.

It’s the final step into what the strip is for the remainder of its run. Freed from the need to accommodate the text McCay could again take a more expansive view, and from that point there’s barely a page that doesn’t look magnificent. Having the option of a larger page, McCay frequently deals in scale. An approaching elephant is tightly constricted within the panels, the characters convert to giant size on several occasions, and a massive dragon features. He also experiments with the possibilities of the printing process. A granny in a robe transforms into a young girl, and over a few strips when she appears her true form is indicated by a ghostly presence hovering over the girl’s head.

As the strip deals almost exclusively with dreams, it’s not greatly dated in over a century. The dialogue is sometimes stiffly formal, but the designs have passed beyond the influence of their era to become timeless, so Little Nemo visits a magical world of costumed elegance that still astounds. Examples of the strip are hardly uncommon online, but it’s not the same as holding a lovingly curated book. And don’t keep it to yourself as a pristine artefact. Ensure you fire the imaginations of your children also.