Review by Ian Keogh

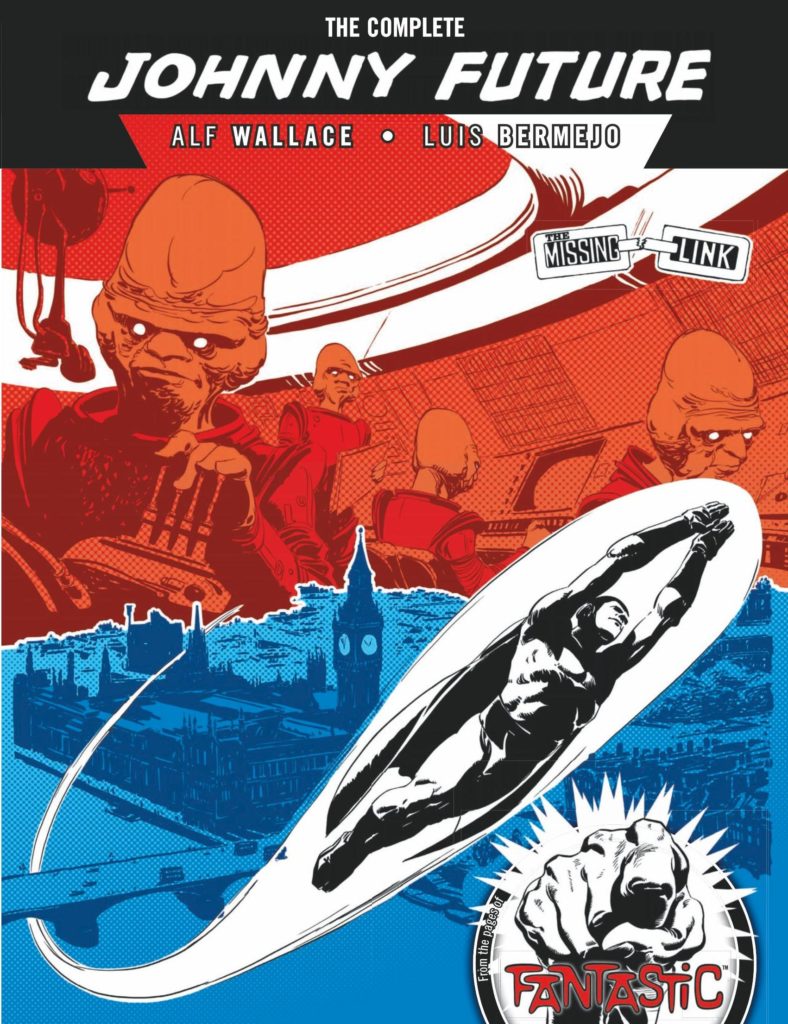

Johnny Future has a unique place in British comics mythology. For most of the 20th century UK comics left the superhero to US publishers. Mick Anglo created new Marvelman adventures in the 1950s, but wasn’t then seen as a forerunner. In the 1960s Odhams gradually introduced more Marvel reprints to their titles to the point where Fantastic was almost exclusively licensed content. The exception was the Johnny Future strip, or as it began, the Missing Link strip.

Over the original strip writer Alf Wallace takes the Incredible Hulk and drops him into a King Kong scenario, the reason for this probably that publishers Odhams in 1967 had reprinted Marvel’s entire run of Hulk stories to that point. Luis Bermejo certainly draws the Missing Link as if the Hulk, and only his polished art redeems those strips, which otherwise never transcend the influences, and feature an incredible amount of unnecessary word balloons. It’s when the Missing Link evolves that the he becomes interesting. His new form is human, but with superhuman strength and a formidable intelligence, yet one that’s not learned English, and he’s convicted for a crime committed by another. Resolving that takes thirty pages in the style of the 1960s British adventure comics serial, where the truth is forever beyond reach, before the change to Johnny Future, which is bizarrely inexplicable. Why our hero needs a costume to stop a guy who controls animals is glossed over, along with several other points during the run, as noted by Steve Moore in the introduction.

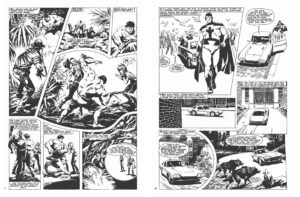

Johnny Future suffers from melodramatic captions and over-writing, but the grace of Bermejo’s art over-rides a lot of concerns. His mastery of ink creates one astounding looking page after another, and he’s an artist who puts equal effort into all aspects of the story. The cast engage with each other in front of fully realised backgrounds, and Bermejo pays attention to architecture, cars, clothing, furniture and assorted wildlife. If there’s a very slight weakness among his talents it’s character design that doesn’t stand the test of time, although when he drew the strips, Bermejo had no expectation anyone would be looking at them a month after publication, never mind decades. Animal Man in his tiger cloak and tiger head helmet is plain daft, and he’s not the only one.

While not all the people Johnny Future comes up against are original, what Wallace does with them generally has an interesting twist. He’s fond of villains able to control something or someone from a distance, Animal Man being one, with real strangeness about his final pages. There’s an intelligent use of what at first appears to be a standard robot, while the malevolent Mr Opposite exemplifies corrupting power and his fate is clever. However, Wallace takes blatant short cuts in other places. An excuse for the company caretaker accompanying test scientists to Scotland is feeble, and he too often resorts to the plot of Johnny falling under the control of others. This type of plot repetition is common to weekly British serialised stories of the 1950s to the 1980s, when the idea that they’d be collected was never considered.

A vast expansion of Johnny’s powers allows a trip through space in the final strip, blighted by primitive colour. Although Wallace’s plots have interesting moments and a strangely placid and often vulnerable action hero, it’s Bermejo’s art providing the highlights. Page after page of meticulously rendered elegance and delicate ink line proves the attraction here and raises the content above average.