Review by Fiona Jerome

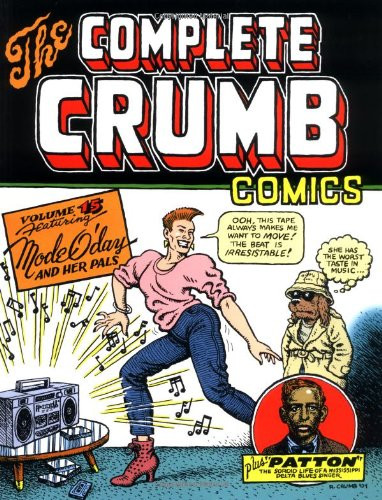

The Complete Crumb Comics Vol 15 sees Robert Crumb experimenting with several new art styles as well as introducing new characters to his repertoire. Containing mostly material from 1983 and 1984 (although a few older things sneak in along with companion work that was done during this period), it features Crumb’s quixotic contributions to his own Weirdo magazine as well as a good deal of commercial work.

In the strong introduction by Peter Bagge, who took over editing Weirdo from Crumb and strengthened its offering considerably, Bagge notes that Crumb was obliged to take a lot of commercial work on in a period when the underground scene was fizzling out and independent publishing was at a low with even established titles like Zap selling poorly. As Bagge notes, you wouldn’t know a lot of the material was done simply to pay the bills. Crumb’s illustrations for Charles Bukowski novels, for instance, are beautifully drawn little vignettes, as are his film posters and album covers. And the covers he drew for Weirdo during this period, in all their perversity, are exquisite.

Much of the first part of the collection is taken up with stories featuring Mode O’Day and her Friends, chiefly a down-at-heel dog and a porpoise. It’s a surreal mix of satire on 1980s culture and funny animal comic set around Mode, an aspiring fashion model. The satire is pretty broad – the emptiness of modern art, the pointlessness of a culture driven by looks alone, people who espouse a political cause simply because it’s fashionable – and the visual style not terribly appealing. Crumb worked with a lot of pattern and cross-hatching, using very few blacks, and creating a lot of textured surfaces, while bringing in some of the angularity of contemporary illustration styles, and it doesn’t quite gel. In previous stories like ‘Uncle Bob’s Mid-Life Crisis’ he had employed a much more decorate open, fine pen style with lots of white space and no blacks. This style had rounded edges, which made it feel instantly approachable. Here the art is sharper, the lines less dainty and far less appealing.

In stark contrast in ‘Patton’, a strip about a blues performer drawn for Zap, Crumb uses a completely opposite style. Inked heavily using a brush, this strip is all about blacks, a stark chiaroscuro universe with almost symbolic marks for shading, reminiscent of the work of Charles Burns, although more realistic in intent.

Mode O’Day and her vapid visions are typical of a continuing cynicism in Crumb’s work of the period, although it is often undercut with humour. Parents of demanding young children will recognise the universal truths in ‘That Thing in the Back Bedroom’, a strip drawn with Crumb’s wife, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, in which they both draw themselves and write their own dialogue, blending their styles to produce completed panels. It’s only really these observational strips that have a balanced worldview, perhaps because of Kominsky-Crumb’s input.

At the same time Crumb continued illustrating interesting works with his excerpts from Kraft-Ebbing’s Psychopathia Sexualis. As you might imagine, there are rich pickings for someone like Crumb, with his understanding approach to sexual fetishes, in a series of case studies of extreme perversions and sexual compulsions. As with his earlier foray into adaptation, working with the diary of James Boswell, Dr Johnson’s biographer, Crumb employs a detailed, etched style to illustrate his pick of Kraft-Ebbing’s cases, often contrasting high-minded text with disturbing or comic images.

Crumb’s work in this period is very mixed both in focus and quality. His grim worldview at the time can be wearing. An interesting rather than entertaining volume.