Review by Frank Plowright

It’s been well over fifty years since the Western had any kind of serious pull in American culture, but the stories told before then filtered through to Europe where the genre has survived, especially in comics. Many of Europe’s top talents have worked on Westerns (see recommendations), and while Sergio Toppi is startlingly individual, all but two of the eleven stories gathered in North America fall squarely within the Western’s narrative territory. For the most part, though, Toppi dances around the periphery, not focusing on the heroic figures of cowboys, sheriffs or army officers, but loners, shopkeepers, and treasure hunters, the latter a theme he frequently explores. There’s a raconteur featured in most, relating their story to the audience, and their tales are unpredictable, some leading to conflict, others casually avoiding it. In many someone is taken to the limit of their endurance, and while presented almost as folklore, with prophecies played out, there’s a strong sense of morality applied.

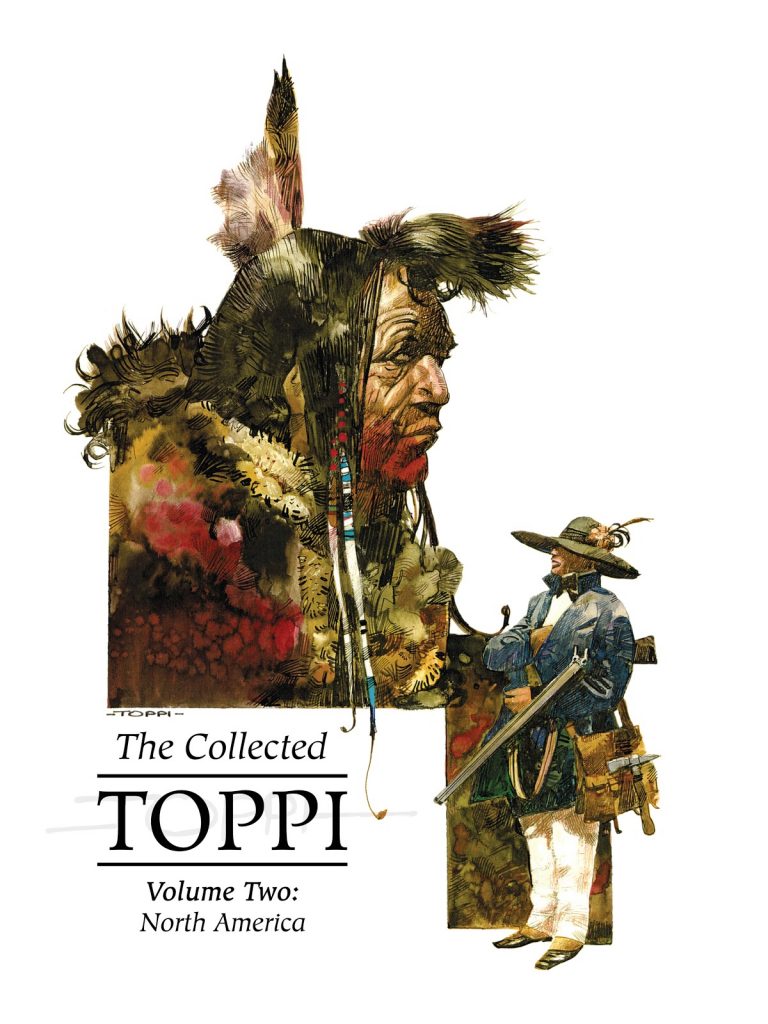

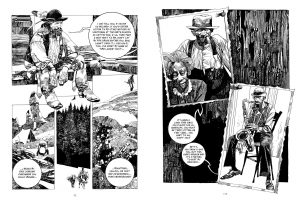

As in The Enchanted World, and in every volume that follows (South America is next), the art is phenomenal. Look at the abstract shapes constructing the wooden slats in the sample art, or the glorious portrait oozing personality and a life lived. Any artist would be happy enough to master either one of those skills, yet for Toppi they’re just part of the package. He has a great affinity for nature, be that landscape or wildlife, and a fascinating way of telling the story in cinematic snapshots. It’s possible to imitate Toppi’s style of storytelling, but doubtful whether anyone could manage it with such panache, although in his introduction David Mack notes a sense that once a creator is moved by Toppi, their work is forevermore marked by his influence. Some aspects of the art seem instinctive, but his page composition is studied and deliberate, the right sample page framing the main characters as if on postcards.

There’s a move down to the Southern US states to investigate the tormenting of Baron Samedi and then follow the winding path of blues saxophonist Honeylips. The latter is the stronger story, about music soothing the savage soul, set in a mythological 1940s, and possibly causing offence via use of the language of the times. What it all means is anyone’s guess, but it’s poetic and surprising, and passes like a sweet melody.

Perhaps there are people who can look at a page of Toppi artwork, yet remain undazzled, the explosion of a master stylist leaving them cold. It’s certainly the case for Jack Kirby’s peak, but this isn’t superheroes. Toppi’s world is a real world with real people, however distant, magnificently realised and any art fan who doesn’t sample at least one of these collections is denying themselves the opportunity to bask in astonishment.

Each of these Collected Toppi volumes features a coincidental bonus as well. Hold a page at the correct angle under artificial light and the black ink on gloss paper will become a bronzed negative image. It’s a beautiful effect.