Review by Ian Keogh

Churubusco has now been absorbed into the vast sprawl of Mexico City, but there’s a reason it hosts a museum dedicated to those who’ve died defending Mexico. In 1847 Churubusco was the site of a decisive battle leaving the US army what was then five miles away from the Mexican capital.

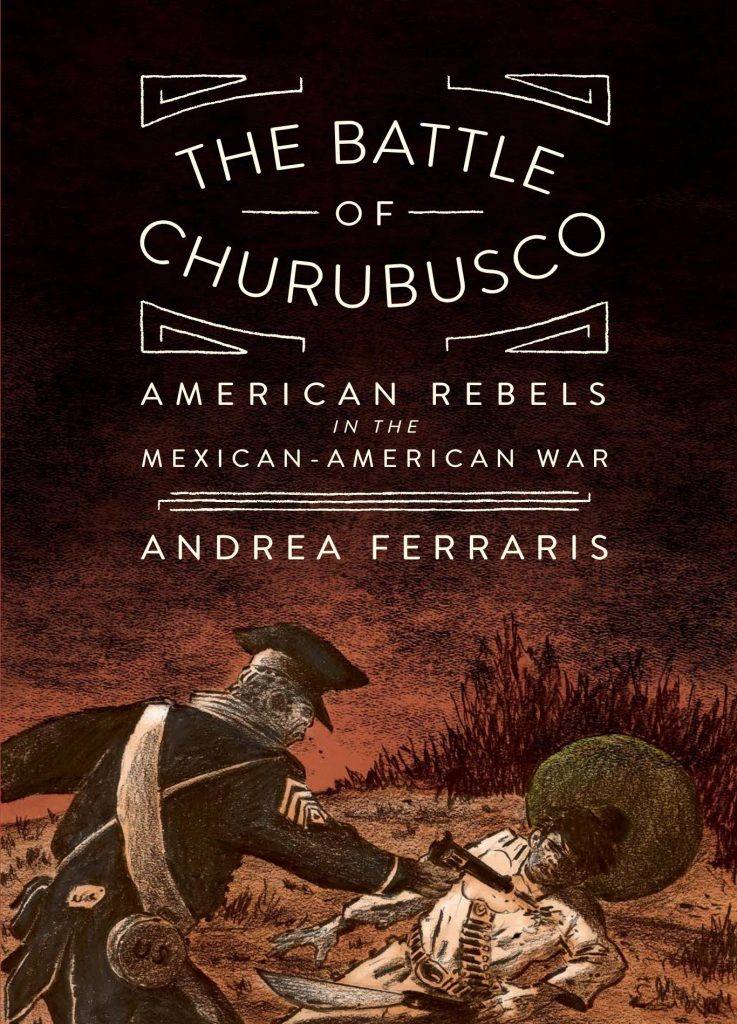

Andrea Ferraris first learned the history of Churubusco via a Chieftans song about the San Patricio (or St Patrick’s) Battalion, a group of Irishmen who deserted the invading US army to fight alongside the Mexicans defending their country. He begins with their fate, some killed in battle by the Americans, survivors branded as deserters before being hung.

The Battle of Churubusco is created as cinematic drama, fiction based around known events rather than factual historical documentation. Almost the entire story is told from the point of view of the Americans hunting down the Irish battalion, focussing particularly on Gaetano Rizzo, their scout. He’s haunted by dreams of wolves, has a conscience absent from some he fights alongside, and is the ideal focus as a man as scorned for his background as the Irish who deserted were. Lost in the landscape, his company are uncertain the place they call Churubuscu actually exists.

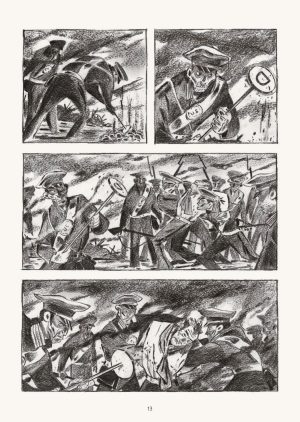

The presentation of yet another superb European artist largely unknown to the English speaking world is always a joy. Ferraris’ long career has apparently been spent drawing Disney comics in Europe. The Battle of Churubusco is a complete contrast, although the storytelling clarity demanded by Disney has surely been embedded, as Ferraris is confident enough to present multiple sequences for pages at a time without dialogue. This is in an effective charcoal wash, adaptable enough to display intimate character moments, the vastness of the land being fought over or the horrific bustle of battle. Ferraris switches to an equally appropriate sepia tone to convey Rizzo’s nightmares, everything impressively designed and laid out.

As Ferraris continues, The Battle of Churubusco title takes on a different meaning altogether as it comes to represent Rizzo’s internal conflict. The dreams he’s been experiencing connect to repressed memories, and his survival depends on his coming to terms with his past. That there is a depth given to Rizzo has the unfortunate effect of highlighting the one-dimensional characterisation of all other parties. Their single personality traits are Western archetypes, and make no mistake, Ferraris is crafting a Western here for all the hisotrical trappings. It’s an iconic rendering and results in a cracking adventure, if not perhaps meeting the expectations of anyone familiar with the history. The bare bones are there, and plenty of sources exist for anyone wanting to research further.