Review by Roy Boyd

All Tintin books since the ninth, The Crab with the Golden Claws, had been produced under the German occupation of Belgium. This, the thirteenth, was to have its conclusion delayed for over two years when the Allies liberated the country.

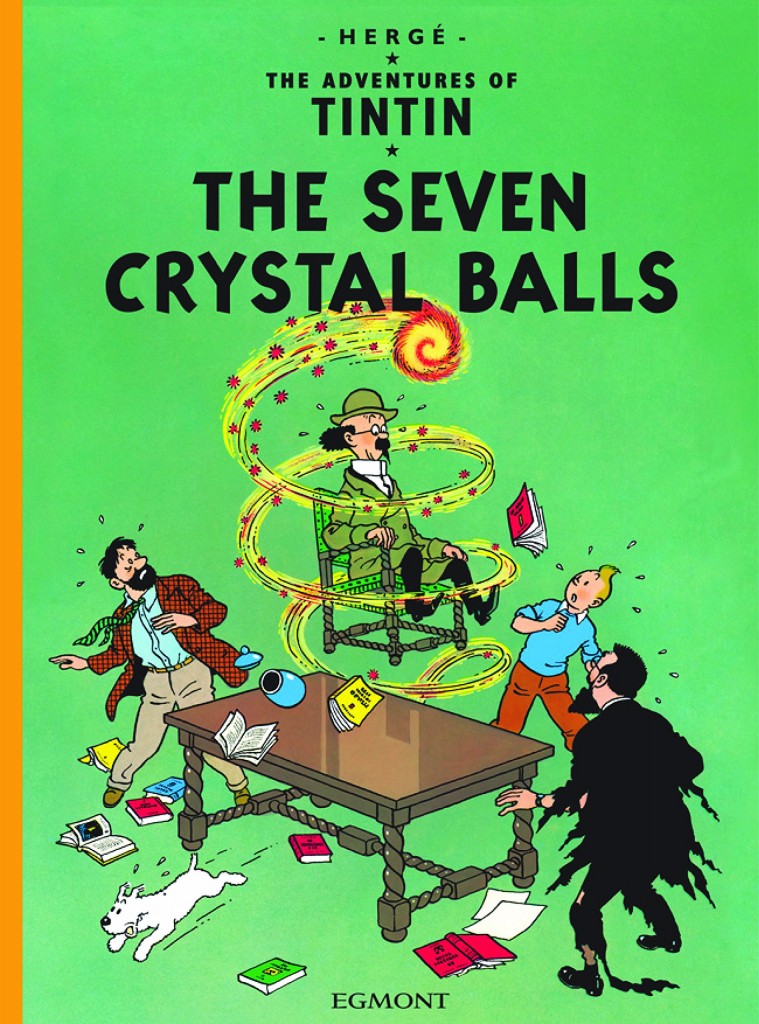

The previous adventure had been spread over two volumes – The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure – and Hergé was to do the same again for this story, which concludes in Prisoners of the Sun.

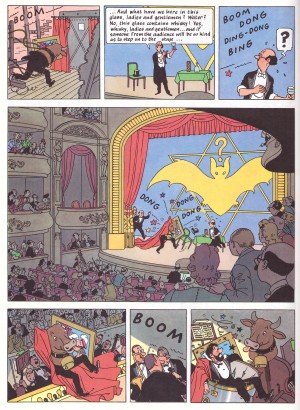

Hergé’s intention had been for the first book to be a mystery and the second an adventure, and he succeeds admirably, kicking off the story with a tale that’s equal parts Sherlock Holmes and Alfred Hitchcock. First of all we have an oppressive opening section very reminiscent of the doom-laden beginning of The Shooting Star (echoing the Belgium’s occupation). A trip to a music hall features a mentalist act that leads into a plot that, like the fourth Tintin book, Cigars of the Pharaoh, owes a great deal of its plot to Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb, and the subsequent curse that supposedly befell the members of the expedition. Before too long returned members of a similar expedition who ignored dire warnings and stolen an Inca mummy are falling into a strange coma, and when Professor Cuthbert Calculus, Tintin’s dear friend, is kidnapped, Tintin and Captain Haddock set out to rescue him.

After the war, the strip ran in the newly created Tintin magazine, which required two full colour pages per week. Add to this the constant redrafting of earlier adventures, and it was clear that Hergé needed help. It was at this point in his career that he began employing assistants to keep up with the increasing demands being made on him, and this practice was soon to blossom into Studio Hergé. An immediate difference was this adventure being the first to appear in colour during its original serialisation, and Edgar P. Jacobs contributed to backgrounds before deciding he’d prefer to concentrate on his own Blake and Mortimer feature. It also meant the heavy research was shared.

Observant readers may notice that Hergé repeats himself quite obviously when, on page 50, Tintin visits Captain Haddock at Marlinspike Hall. In fact, the repeated scene was deliberate, with the second one indicating that it was time for a fresh start. Haddock, at first dejected and miserable, pulls his figurative socks up and sets off after their missing friend with a determination that was clearly autobiographical. Belgium had just been liberated by the Allies, and Haddock’s reawakening was Hergé letting the world know he was hoping to put the situation created by the war behind him and start again with a clean slate. It would prove to be a vain hope, and he was plagued for many years by accusations of collaborating or being sympathetic to the Nazi’s cause.

Critics have compared this adventure to a Sherlock Holmes story, which is surely no bad thing, and it contains many overt supernatural elements, like voodoo dolls and shared dreams, some of which aren’t given a rational explanation. In terms of quality, Hergé had matured to the point when things were rarely less than superbly well crafted, and this is a good example of what Tintinologists consider classic middle-period Tintin. Not quite as memorable as the preceding adventure, but a very worthy addition to the series.