Review by Frank Plowright

Unscrupulous politicians in English speaking countries know it’s far easier to generate votes by demonising people desperate for help than by offering solutions to difficult problems that might improve their country. They lump together people who’ve experienced vastly different personal circumstances into one homogenous immigrant mass depicted as threatening. That in some cases those lacking basic human compassion are themselves from immigrant families is almost beyond irony.

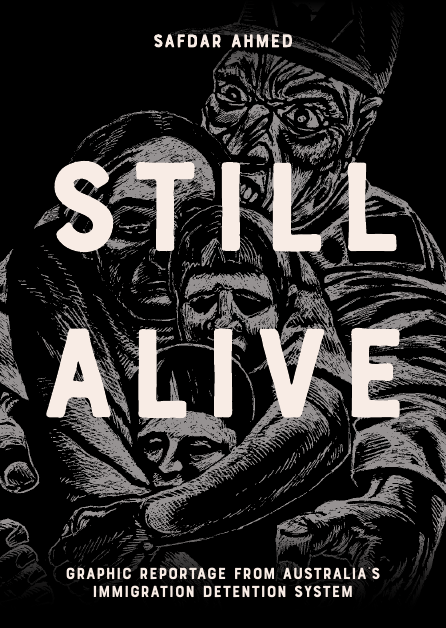

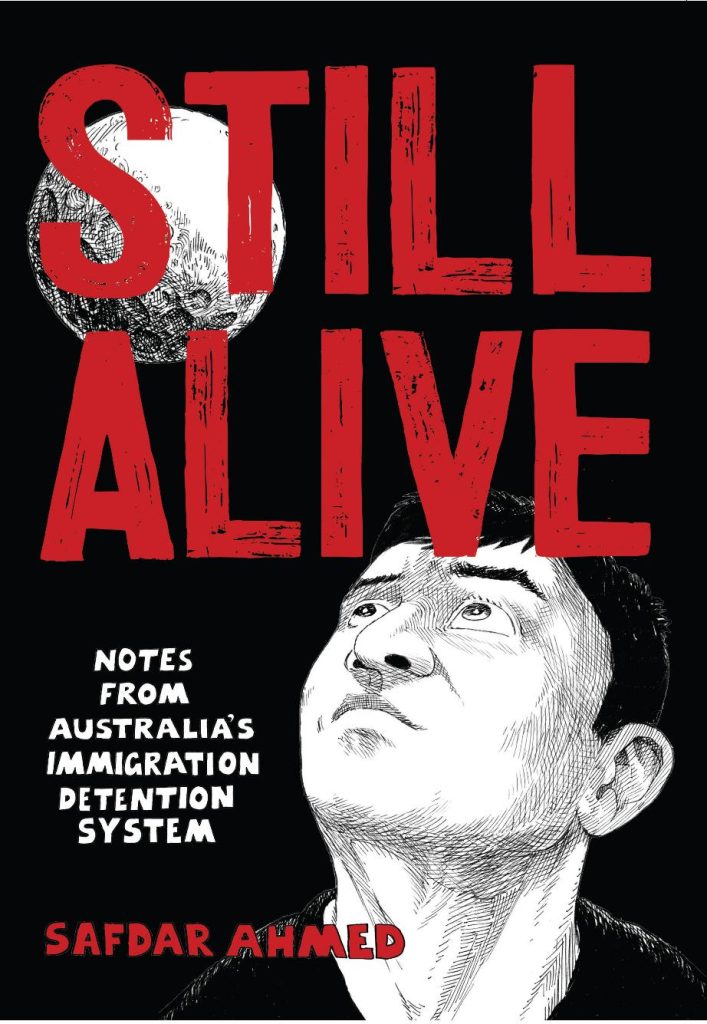

What the larger public don’t really know is how a person fleeing their own country is treated by immigration systems supposedly acting in accordance with the United Nation’s Declaration of Human Rights. In Still Alive Safdar Ahmed highlights Australia’s Villawood Immigration Centre in 2011, but the equivalent systems in the United Kingdom or the United States are surely no improvement. Those seeking immigration are largely afraid to speak out for fear of jeopardising their prospects, and with scrutiny minimised, intrusive practices, lack of understanding and a bullying culture flourishes.

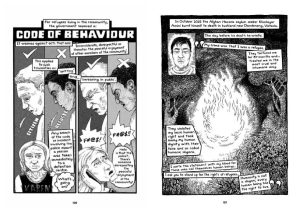

As Ahmed notes of the incidents he relates, deprivations and abuse result in mental illness, and most refugees view the system within which they can remain for years as being designed to punish, not process, contrary to Australia being a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention. To take just one example Ahmed relates, a Sri Lankan refugee is showering when an immigration official bursts through the door of his accommodation during a “welfare check” that can occur any time of day and night, and several times over 24 hours. Believing it’s an emergency, the man rushes naked from the shower, resulting in a complaint from the female immigration officer that must then be investigated. Transfer those circumstances to your home and consider how you’d feel.

It’s a comparatively trivial incident, though, compared to the deaths and maltreatment recorded by Australia outsourcing its refugee operations to nearby Pacific states. Until declared unlawful, the standard Australian government response to any revealed incident was to declare it the responsibility of the island concerned, nothing to do with them. Is that form of one-step deniability what the UK plans in Rwanda? When the centre on Nauru was closed the Australian government preferred to pay millions of dollars in compensation than have evidence publicly aired in court.

Ahmed’s form of reportage is indebted to Joe Sacco, down to the placement of narrative captions at an angle, but as yet he’s a more limited artist. That, though, is inconsequential when weighed against the information he’s delivering. None of us would want to walk a mile in the shoes of the people whose experiences we hear about either before or after they arrive in Australia, yet in our name throughout the world others undergo similar indignities on a daily basis. Could anyone read these experiences and still fail to understand?