Review by Karl Verhoven

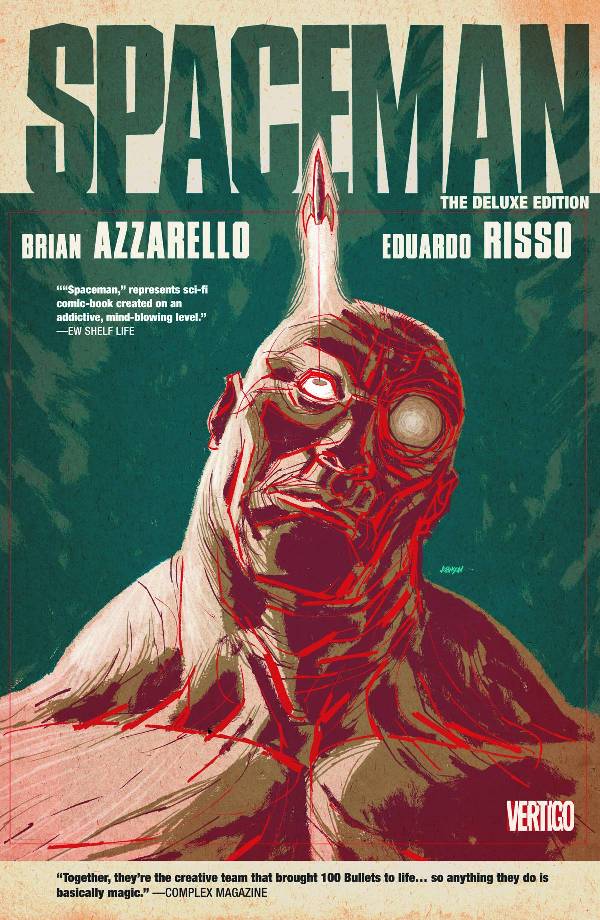

Spaceman is a graphic novel that defies expectations, firstly via the title. It’s a sarcastic term applied to the protagonist Orson, none too bright and scratching a living the best he can on what’s left of an Earth ravaged by the consequences of climate change. This is a book of contrasts, and Orson was once a symbol of a bright future, one of several children genetically engineered by NASA to survive manned missions to Mars. The plug was pulled, but he still dreams of what he might have been, when fate delivers a possible better future.

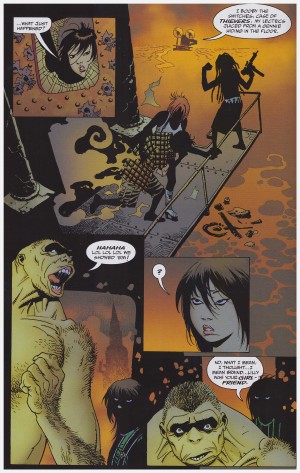

The planet is hooked on The Ark, video feeds in which orphaned children compete for the right to be adopted by a celebrity couple. Yes, Brian Azzarello’s very dark sense of humour is in operation again, and the bleakness is extended when Tara, one of the children, is kidnapped. This is a world where all bar the most pampered children learn early that life is cheap and how to duck and dive, and that when an opportunity presents it should be taken. It’s a shame, then, that Orson’s capabilities hover around the bare survival threshold.

Innocence contrasted by knowing cynicism is Spaceman’s theme, with Orson’s good intentions reflected darkly by the world of manipulation surrounding The Ark, where everything is spun to maximise viewers and income. Contrast is also the abiding factor of events on Mars, elaborate fantasies constructed by Orson in which he extrapolates on what might have been, characterised by his own sense of limited self-worth. Yet when confronted by reality he’s far more than he considers himself to be.

Azzarello’s comics always contain excellent dialogue, but a commitment to being true to life means the content will be offensive to some. As if giving a deliberate finger to critics who’ve labelled his dialogue difficult to follow, Azzarello indicates the underclass of the future via the construction of new nouns and adjectives: “Bizz in the rise. It’s fished out. Too many junkers. Real bizz is out beyond”. In context we supply the synonyms, but it requires thought.

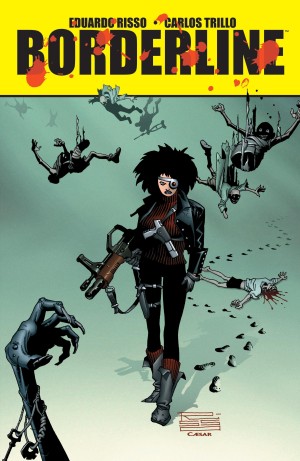

The thought needed for Eduardo Risso’s art is merely appreciation. Still using a stark, shadow drenched style, there’s a warmth to his cast, many of whom are children, and the world he creates is astonishing. It too presents contrast, conveying the dispossessed and the dissolute in their environment, yet beautifully drawn, with Patricia Mulvihill’s bold colouring providing an unearthly glow.

Orson and Tara’s destinies eventually entwine, and the way he imagines himself runs contrary to what occurs when he finally meets one of his brothers. Tension escalates as a well-meaning and gullible protector doesn’t appear up to the task, and Azzarello surprises with a cynically amusing conclusion.

Spaceman wasn’t well received on publication, certainly not helped by initial serialisation when obviously written as a complete graphic novel, nor Azzarello’s contrary attitude regarding speech patterns. Beyond that, it may be too clever for its own commercial well being. All the information about the trickier elements is provided, if sometimes by a single line. However, readers embedded in a culture in which subtlety is derided (satirised in situ) and the speed read is all will dismiss this with ease. Those who prefer a more considered read ought to be satisfied.