Review by Frank Plowright

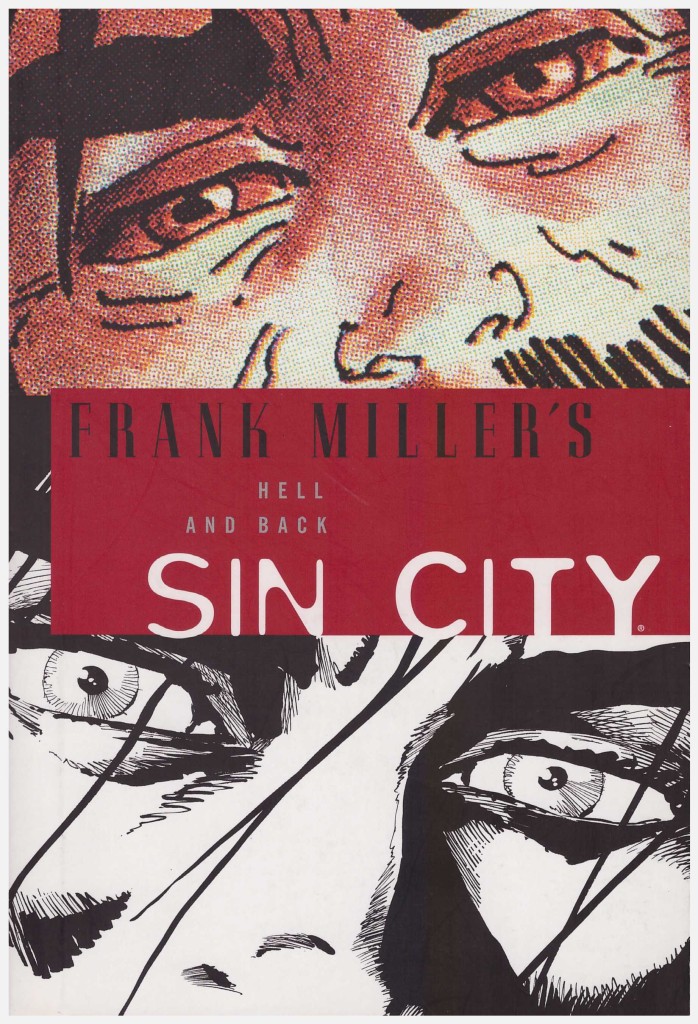

Hell and Back is very much a departure for Sin City in several respects, most obviously via use of considerable, if not full, colour. A hallucinatory sequence approaches this, though, and the distinction is a simple and effective method of portraying disorientation in the black and white world of Sin City. Other colour is used for a woman dressed in an orange catsuit, and for a woman in blue, whose pedigree will be familiar to those who’ve read Booze, Broads & Bullets.

This is both the last and longest of the Sin City titles, and a further distinguishing aspect is that for the first time there’s some sloppy artwork. A woman integral to the story is illustrated in positively gruesome fashion on occasion, and there are distortions beyond stylistic preference to another character used toward the end of the book. Cars, so fetishistically rendered throughout Sin City, are here sometimes compressed, and there’s no consistency to the overall look, which switches as the story advances as if Frank Miller’s shedding styles along with the series.

The visual inconsistency is a shame, because the plot is among the strongest Miller produced for the series, with an emotional core not always previously present. We’re introduced to a new character, Wallace, now an artist, but a man of style and principle with a very capable background. While driving alone late at night he prevents the glamorous Esther from committing suicide. They only spend a brief time together before Esther is abducted, but Wallace is determined to track her down in the face of an indifferent and corrupt police force, and ever-escalating threats.

Previous books have focussed on obsession and lust, but this is the closest the title approaches a pure love story. Miller is dealing in broad strokes, so Esther is an angelic representation, and the first woman we’ve seen in the series who could be described as normal and innocent.

As much as he experiments with his art, Miller’s also playing with the narrative, switching his methods. A hallucinogenic sequence isn’t merely an excuse to drop in cameos from other characters Miller’s worked on in a disoriented miasma, it continues the story in clever fashion. Having a pivotal sequence recounted in hindsight removes some of the sting, but an initially puzzling diversion in which a schoolboy is beaten up, is well inserted. Miller switches from cartooning with the biggest of big feet to a more familiar style for Sin City as the pages of this segment progresses, and the innocence is accentuated by these pages featuring far more white space than is common.

Those preferring to immerse themselves in Miller’s bleak and sordid world of crime can do so with Big Damn Sin City, an oversize hardback collecting this along with every other book in the series.