Review by Karl Verhoven

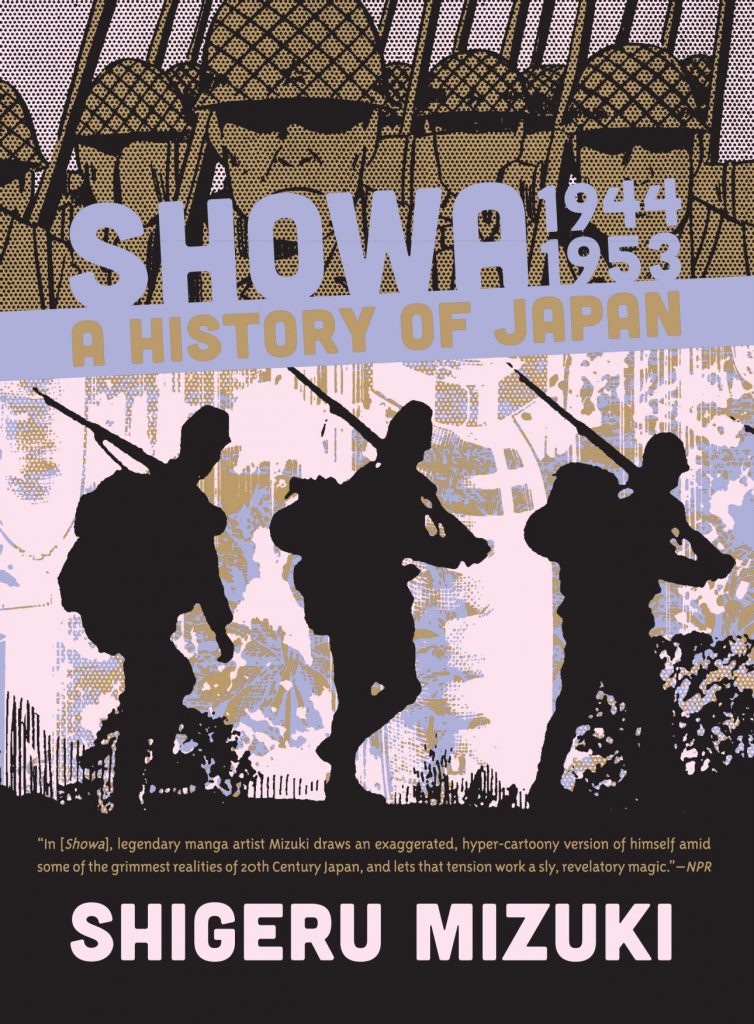

This third volume of four combining Shigeru Mizuki’s autobiography with the history of Japan’s Showa era (1926-1989) unites the narrative threads far more closely than previously as both nation and author experience a prolonged period of soul-searching.

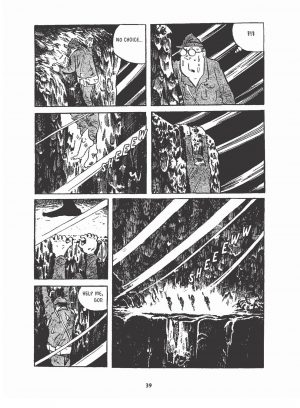

Mizuki picks up at a point where it’s already apparent to those not blinkered by blind faith that Japan’s World War II expansion has exceeded its capabilities, and defeat is inevitable, yet it drags on until the atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The opening chapters deal with the disastrous occupation of Burma and subsequent retreat, then Mizuki’s own experiences in Papua New Guinea, attempting to survive in hostile territory. He produced Showa, so we know he does, but he’s so good at portraying the tensions there are moments of doubt. The sample page is from this section, and he faces worse situations.

Mizuki supplie rich historical detail necessary to explain complex and ever-shifting situations involving several countries, but it’s possibly too dense for the casual reader over the first half of this book, even taking his phenomenal art into account. The detail on a page of battleships is eye-straining, leading to wonder about the size of the page Mizuki drew on. For Westerners he’s unable to explain the ingrained concept of why it’s more honourable to die than to surrender, and quotes the deluded General Tojo as saying “I’d rather see the death of the entire country than admit the smallest defeat”. Ironically Tojo survives World War II to be tried and hung as a war criminal. Mizuki’s own survival is down to several strokes of good fortune, although he eventually loses an arm, and he never lets us forget the human cost of Japan’s failed campaigns. “Human life is the least valuable resource in the Japanese army”, he writes, continuing “any suggestion that soldiers’ lives have meaning is tantamount to cowardice and treason”. Nor does he whitewash Japanese cruelty toward their own civilians, his family house torn down in order that it doesn’t catch fire during American bombing raids.

Although covering the period stated on the cover, over 400 of the 530 story pages only take us through to 1946, and even then only a few later personal experiences separate Mizuki’s thorough explanation of the reforms to Japanese society once the US occupiers arrived. Democracy is prioritised over the old ways, instituting massive changes with binding modifications to the constitution. Big problems occupied the authorities, and Mizuki’s account of his immediate post-war life almost has the same hallucinogenic quality as his time among the natives of Papua New Guinea during the war. His surreal experiences are partly presented as comedy, but he represents millions of other Japanese without purpose. While his war service is harrowing, this lost period is equally so for highlighting a different form of cruelty, that of neglect.

For all that, Mizuki’s looking back from a time of comfort, and so able to weave these final pages as a form of mystical realism with one bizarre occurrence after another. While he’s suffering at the end of the 1940s, his experiences in hindsight selling fish and renting rooms are the light relief after the war. By the end he’s discovered his career, which is covered in 1953-1989.

While the accessibility of the historical detail is an achievement, as with 1939-1944, the sheer density of it, even when separated by Mizuki’s personal experiences, makes this slightly less desirable than Showa’s first and final volumes.