Review by Karl Verhoven

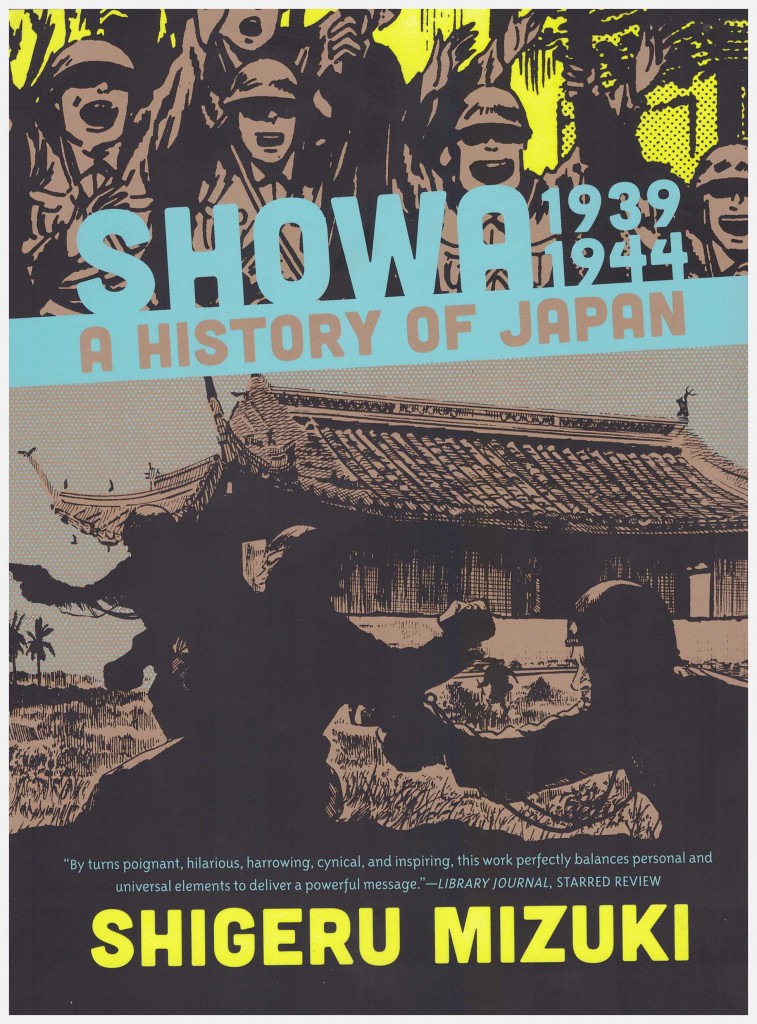

Shigeru Mizuki’s combined history of the Showa era (1926-1989) and his autobiography continues with an extremely compressed period. In terms of the sheer work involved and information imparted 1939-1944 is every bit the equal of its impressive predecessor, but it’s less engaging overall.

Mizuki comments on the political and military decisions via his stand-in Nezumi Otako, one of his characters known throughout Japan, and this commentary is contentious in a nation where the respect for tradition and office prevails. Such is his artistic standing, though, he’s able to do so from his own position as a recognised “Master”.

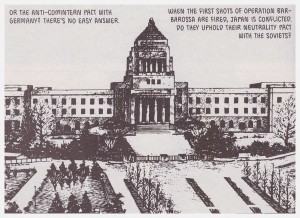

“Even the children of Japan yearn for war against the West”, advised General Hideki Tojo, Prime Minister from 1941, “we must give the people what they want.” Japanese tactics of surprise attacks by air and sea initially ensured victories throughout the Asian region. Such was the rapidity of this territorial gain that the head of Naval Intelligence proclaimed “We will make a triumphant entry into London and parade our battleships in New York.” The succession of victories was halted with a crushing naval defeat at Midway in 1942, but it wasn’t until after Japan had surrendered to end World War II that most Japanese learned of this loss. It also marked the end of expansionist policies as Japan lacked the resources to hold territories they occupied.

Tojo is recalled in the west as a merciless warmonger, but his standing in Japan remains contradictory. Mizuki highlights his obsession with staying in touch with ordinary people, which manifested in his scarcely believable habit of checking garbage cans wherever he visited to ensure there was no waste.

What renders this volume a slightly lesser work than 1926-1939 is the smaller percentage of pages devoted to the personal and social details that illuminated the bigger picture and leavened the necessary dry historical fact. This is partially due to Mizuki having already produced his personal war memoir, Onward Toward our Noble Deaths, albeit almost thirty years previously. The recollections here largely concern the brutality of his training, which continues during active service. It’s not until page 382 of 538 that there’s any insight into the lives of ordinary people in Japan as they’re fed daily propaganda about the accomplishments of the nation’s armed forces.

It’s deeper in at only a hundred pages before the end before some extended personal recollection from Mizuki, as he becomes involved in battle. Then only twenty, throughout he portrays himself as seen by others, not many steps removed from a feckless glutton, although one sequence recalls his study of philosophy in his own time. This was an attempt to cull sense from life and death during a period when he considered his own death likely. It’s also telling that he’s the only one of the occupying Japanese to visit the native villages where he’s stationed, which will have lasting personal consequences in the next book, covering 1944-1953.

Mizuki’s photo-referenced art is stunning, yet his frequent use of two landscaped panels per page recalls nothing so much as a more accomplished form of British digest war comics like Commando. These are supplemented by reproduced photographs on occasion. He varies his styles, though, from naturalistic cartooning for historical figures, to a more traditional form of cartoon illustration for his own family members and his commentator Nezumi Otako.

In Japan Showa was published over eight volumes from 1988, but Drawn & Quarterly have repackaged them as four books on pulp paper, reading from back to front and right to left in traditional Japanese manner.