Review by Ian Keogh

Drawn & Quarterly’s translations of Kitaro concentrate on the five years between 1967 and 1971, and that’s the case for the seven stories included in Kitaro’s Yokai Battles. As ever, there’s no great continuity to the adventures of the one-eyed monster boy, other than that of translator Zack Davisson’s informative introductory essays. The one included here relates Shigeru Mizuki’s unlikely success as a songwriter, and the reason he transformed his Kitaro feature into its more child-friendly incarnation.

Perhaps that depends on your definition of child-friendly. Like European fairy tales, the legends of Japan’s Yokai are often cautionary, featuring gruesome events, and at face value Kitaro’s stories acknowledge this. In the first of this selection Kitaro’s broiled in a pickle pot, the second has a young girl aware she’s due to be sacrificed to appease the hair god living in a mirror, and the third has a pair of children orphaned when their father is sucked up by a whirlwind. While Kirato invariably wins out, not everything is restored to the way it was every time, so emotional tragedy is a regular story component.

That second story has little involvement from Kitaro, and his sidekick Nezumi Otoko acts more as witness and narrative voice, and with a theme of a village targeted by a malign presence demanding the sacrifice of a young girl, it echoes European folklore. A similar theme is explored in the final story of a man whose life is saved by a Yokai and reluctantly promising his daughter as its bride when she turns sixteen.

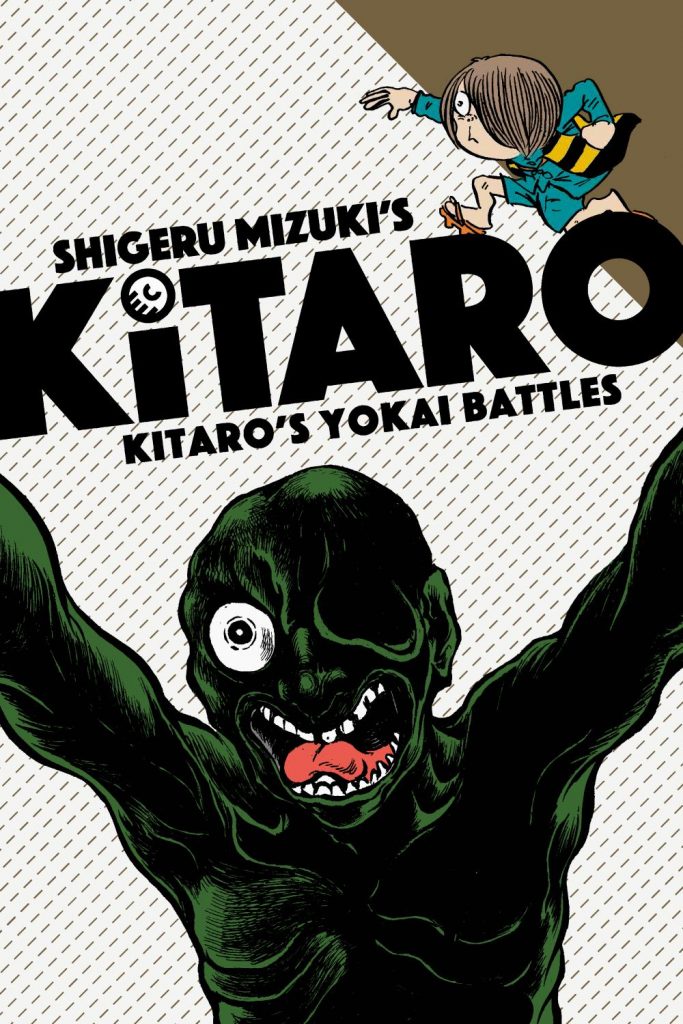

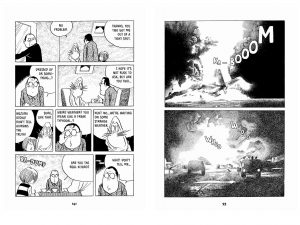

Moreso than any previous volume to date, this selection showcases Mizuki’s illustrative mastery, with a greater selection of moments mixing the simple cartoon figures with ornately rendered backgrounds. Mizuki’s preference is to render nature, be that forest, sea or sky ultra-realistically, with the military scenes on the right hand sample page more reminiscent of something to be found in his subsequent Showa series. That’s from the fourth story with the grotesque monster seen on the cover, the Doro Tabo, attacking Japanese pilots, and that story later features a creepy illustration to match any horror artist of several mud creatures crawling over a rocky hill. The Doro Tabo is yet another creation missing an eye, something of a series theme also used in in the third story, and representing Mizuki’s skill in designing monsters. One isn’t that far removed from the Gruffalo, yet was created thirty years beforehand.

Mizuku inserts himself into the most playful story ‘Oboro Guruma’, in which he interacts with his creations, inviting them into his home, where Nezumi finds it hard to suppress his natural instincts in exchange for comfort. However, it’s what Kitaro attracts that at first provides the main problem in what’s densely told at a minimum of eight panels per page for much of a story taking some wacky swerves. There’s space to include Mizuku’s homage to classic horror movies, a meeting of the Japanese government, the equivalent Yokai parliament, and a visit from a foreign spiritual leader. It’s like some Marx Brothers fantasy, and not the best of this collection, but the novelty takes it a long way, and it ends by referencing Mizuki’s Kitaro song.

There’s a vast creativity to Mizuku’s Kitaro stories, even allowing for him sourcing much of the trouble from Japanese Yokai legends, and his twisting of them produces another dose of delight. There’s more to be found in The Trial of Kitaro.