Review by Frank Plowright

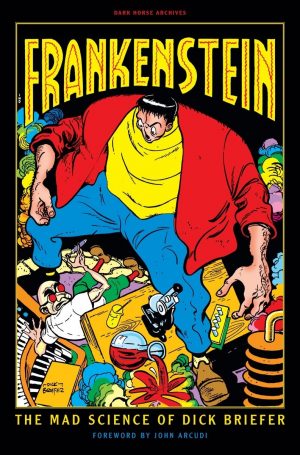

There have been few artists in the history of American comics who’ve combined Basil Wolverton’s sheer manic energy with such a natural talent for the grotesque and an endless wellspring of rhymes and puns. His 1940s work can be seen as a stopover in a line of American comedy comics stretching back to the more surreal newspaper strips of the 1920s and leading to Will Elder’s 1950s Mad strips and onward to the underground comics of the 1960s and 1970s.

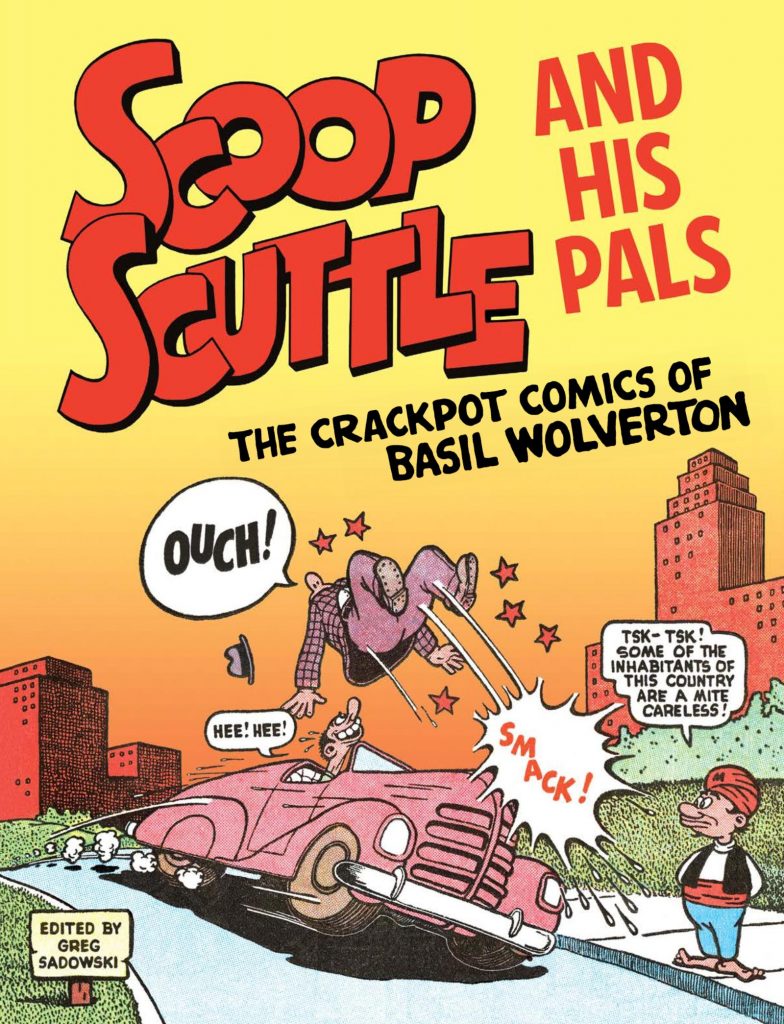

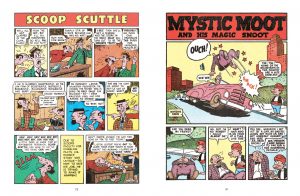

Scoop Scuttle is the title feature by virtue of editor Greg Sadowski locating more of his strips than the other features. Producing the collection required considerable detective work unearthing the strips in the first place (and some are still missing), and even greater restoration skills bringing them up the standard readers would expect from an archive project. Sadowski’s notes precede each batch of strips, giving context and explanations.

Every Scoop Scuttle page is packed, not just with verbal dexterity and elastic expressions, but insane amounts of background commentary forced into each panel. That’s the heart of Wolverton’s art, causing a panjandrum conundrum, as he’s a master of a fast-talking style of humour whose appeal is long in the past. It’s possible to admire the verbal dexterity, and the excess of background detail certainly influenced Elder, but page after page of slapstick puns, alliteration and mugging expressions is a wearing exercise. Robin Williams was a comedy genius, but he could also be tiresome when constantly picking at words addressed to him, riffing gags around them and extrapolating into something else, and that’s Wolverton’s speciality. Four pages once a month in an anthology comic would have been a sweet portion in the 1940s, but the overdose of 68 continuous pages of the scheming newspaper reporter is like being nailed to a chair with Groucho Marx sitting across the table from you snorting cocaine and rabbiting away. Yet, how else should the work of a master be celebrated but in his own anthology?

Thankfully Wolverton refined his art, and the later strips can still appeal decades after he produced them. There are fewer examples of Mystic Moot and his Magic Snoot, western comedy Bingbang Buster and SF hero Jumpin’ Jupiter, but Wolverton has slowed down. By anyone else’s standards these are densely packed strips, but no longer just reliant on wordplay and stringing gags together. Wolverton applying greater thought to the plots. They’re still farcical knockabouts with a heightened sense of absurdity, but there’s more to admire than just the thick lined figures, and the Jumpin’ Jupiter strips are characterised by an even greater visual imagination.

Although Wolverton worked his entire career in the USA, and his influences and those he influenced can be seen, his sensibilities are more attuned to the cartoonists who revolutionised British children’s comics in the 1950s (see recommendations). Like them there’s an occasional lapse of judgement that can be attributed to an unthinking adherence to the attitudes of the times, but he shares a high work ethic, great skill, anarchic humour and visual ingenuity. That stands the test of time.