Review by Ian Keogh

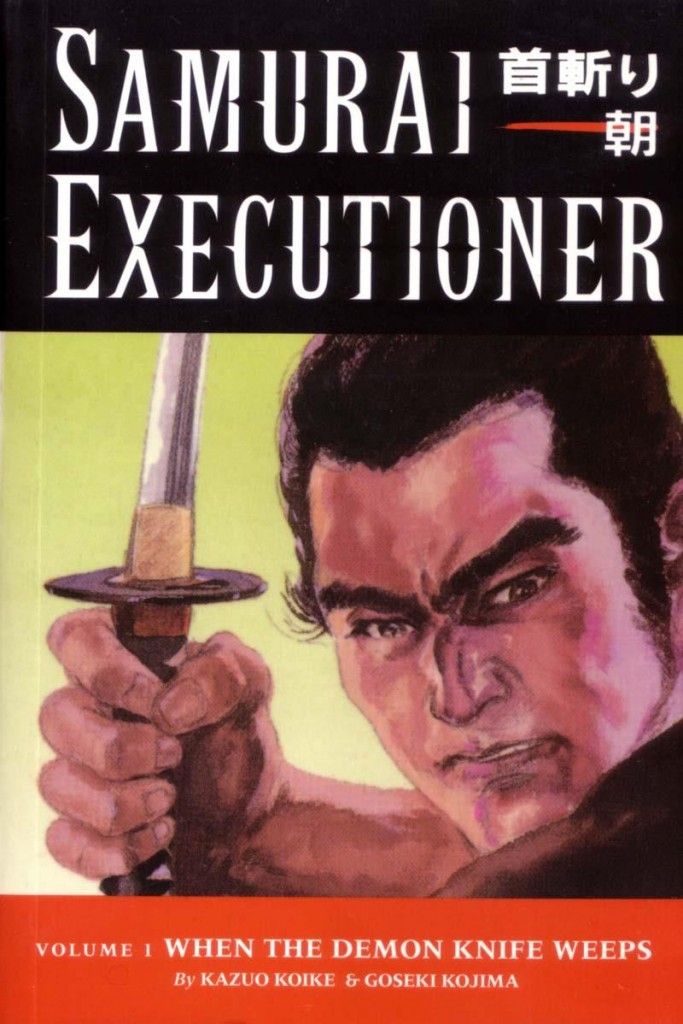

When they began Samurai Executioner in 1972, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima were already two years into Lone Wolf and Cub, the success of which didn’t transfer to English language readers for over another decade. This is characterised by a similar attention to detail in the service of an incredibly rich historical and cultural investigation of Japan’s Edo period, equivalent to the early 1600s to the mid 1800s on the Western calendar.

Of all Asian traditions perhaps the one least understood in the West is the perception of family honour and prestige taking precedence over any other considerations, this often transmitting as harsh and cruel beyond Western understanding. It arises early in Samurai Executioner as Yamada Asaemon inherits the family mantle of sword tester for the Shogun. The role requires considerable skills, and he’s trained since the age of ten on corpses from the local prison, yet for his final test he must cleanly execute a living person. The night before this test, his father insists he undertake a final practice session by killing him.

This is far from the only shocking moment. These vary from the ceremonial execution process being conveyed in historically accurate, detail over forty gruelling pages, through the deliberately crude and provocative language used by criminals, to a criminal’s mother being paraded before him and told she’s equally responsible for his crimes and will be executed. The crimes depicted are appalling, leaving readers in no doubt the perpetrators deserve their eventual fate, indeed willing it to occur, inducing a complicity.

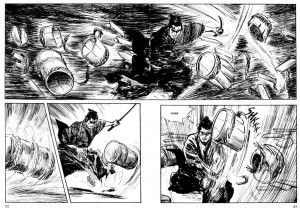

As the sample page shows, Kojima’s loose and sketchy art is brilliant at depicting motion, in this case the title character displaying his prowess with a sword, but elsewhere it’s sometimes a little rough around the edges. There are slight distortions to his heavily inked figures, such as flat looking faces, and when the viewpoint is from above people appear to be floating. The smudginess to the characters may be deliberate, but as Koike’s plot kicks in the initial strangeness of this wears off, and Kojima’s visual characterisation shines through.

Once Yamada has been introduced, the spotlight shifts, and with each new chapter he’ll disappear for dozens of pages at a time as Koike and Kojima concentrate on assorted criminals, establishing their motivation and viewpoints. Yamada’s intervention, however, is final and ends a chapter. There’s no post-mortem, no pages spent moralising about what’s occurred. It’s extremely surprising to begin with, but compact and effective, as what needed to be said has already been conveyed. This is in a society where arrest equated with guilt and proof of innocence was laid on those in custody.

The final story is astonishing, heartbreaking and memorable as Koike and Kojima turn their attention to the woman whose job it is to clean the decapitated heads of the executed. In a complex psychological character study the degradation of her current life is set against the circumstances that led her to it. Much is related via Kojima’s illustration alone, and his storytelling strengths are exemplified.

The horrors of what’s shown and the brutality of justice make Samurai Executioner an extremely intense read, far more so collected than when the original chapters were serialised. There’s a sense of wallowing in the mire of depravity that eventual brutal justice doesn’t entirely dissipate, and emotionally it’s perhaps better read with a gap between chapters rather than absorbed in the single sitting. Those really wanting to wallow can read this combined with the following Two Bodies, Two Minds as the first Samurai Executioner Omnibus.