Review by Frank Plowright

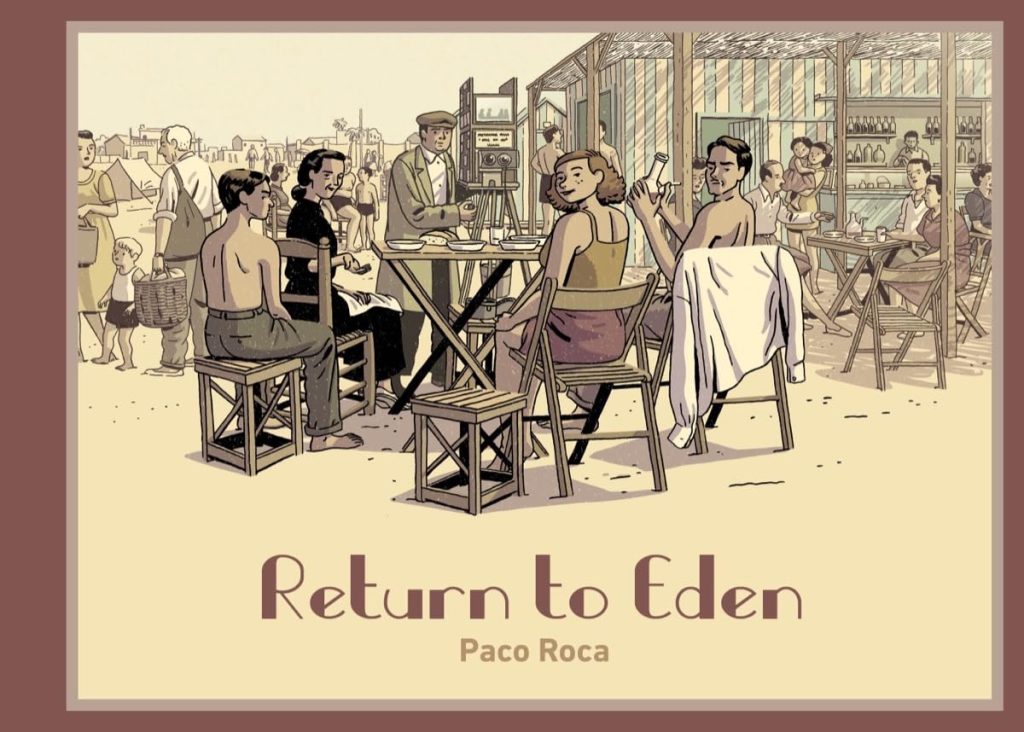

Return to Eden begins with the novelty of completely black pages that then start to feature brief sentences addressing the concept of what comes before and after a life in terms of particles uniting to form it. The blackness then begins to feature abstracted patterns that gradually become extremely miniaturised versions of the pages that follow. It’s quite the way in before we discover Paco Roca is examining his mother’s childhood.

Much of Roca’s translated output has been either autobiographical or biographical material, yet never produced in the traditional method of examining life from birth. His approach can hinge on specific recollections reconsidered, mystery, or in this case the few photographs existing of his mother’s youth. He uses one in particular to explore her family’s lives in Valencia after Franco and his fascists had extinguished the dream of a Spanish republic in the early 1940s. In his mother Antonia’s case this life was one of constant institutionalised hunger and poverty.

The family picture and those on it or missing from it are the subjects of Roca’s stories, woven with subtlety and deftly considered connections, for instance drawing a parallel with the particles of the introductory sequence and the weight his mother lost in old age. The nuances are artistic also, the older brother Antonia worships as a child is depicted as the Vitruvian Man, or the panels within a tier being of a view separated by decades. Even when not impressing with techniques, the solidity of the detailed small panels shows Roca as a thoughtful and skilled artist.

His revelations come slowly and surprisingly, yet also naturally, accumulating into a loving recollection. Whereas some might be ashamed of a parent’s lack of education or knowledge, Roca sees beyond to the kindness and humanity within. The title refers to Antonia’s childhood fascination with the Biblical story of Adam and Eve as defined by the pernicious Catholic church she attends, using it to justify the secondary status of women and as a promised land to which the virtuous will return. The fables she absorbs at church, at the cinema and most often from her mother shape her worldview in the absence of a conventional education.

One by one we learn about other family members, who can be categorised as archetypes matching those Antonia sees in movies. In broad terms there’s the long suffering mother, the tart with a heart, the dreamer and a villain. Together they provide the story of why Antonia is accompanied by the photograph her entire life. It’s most definitely heartfelt, yet also sorrowful, and damning of a regime where all dreams were quashed. Masterful.