Review by Frank Plowright

North Korea maintains one of the world’s most secretive regimes, and for its repressed citizens, the most isolated. It’s a country still technically at war with its Southern neighbour sixty years since an uneasy truce was organised, and which has in the past few decades endured several natural disasters and others human in origin. Some aid has been delivered, but more refused as conditions include co-operation with the international community.

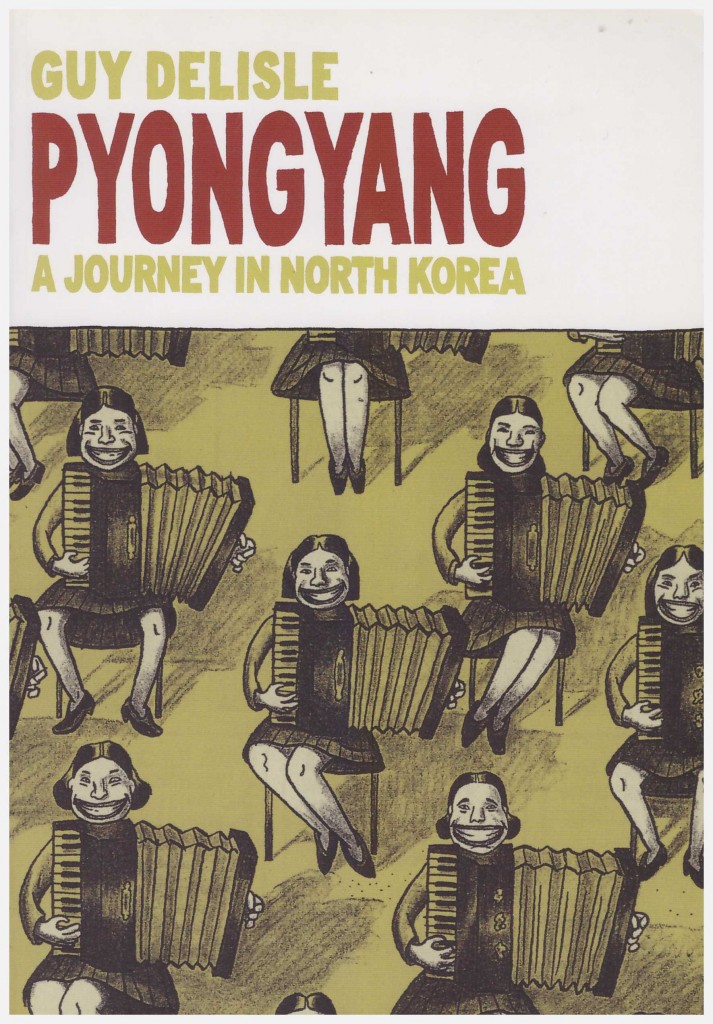

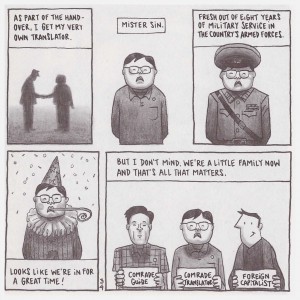

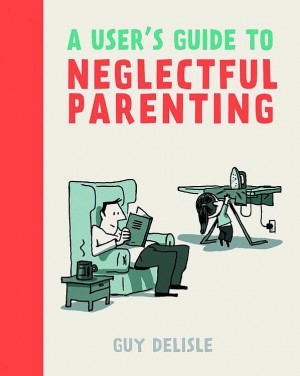

In 2001, prior to the regime being passed to Kim Jong-Un, French-Canadian cartoonist Guy Delisle spent extended periods in the country overseeing work being carried out for an animation studio. He provides a rare observational glimpse into the workings of the country and the lives of the North Koreans.

This is a powerful recollection retaining its capacity to shock. The lives of ordinary North Koreans are entirely controlled by a state apparatus that’s ruthless in dealing with any internal opposition, and heartless in caring for its population. The average North Korean endures a life most of us can’t imagine. One example provided by Deslisle is that everyone works a six day week, but on the seventh they’re encouraged to “volunteer” for work necessary to the state, such as whitewashing stones.

While in the country Delisle deliberately chose to read George Orwell’s dystopian fantasy 1984, and parallels are many. Because a climate of fear is all-pervasive citizens are frequently denounced by their neighbours, and long prison terms result from such “crimes” as listening to foreign radio broadcasts. Workers on building sites are “encouraged” by state propaganda delivered via ear-splitting amplification. The state controls the foreign aid food shipments, which are then allocated according to a classification based on loyalty and usefulness to the state. In a moment of whimsical generosity Delisle passes on 1984 to his interpreter.

Delisle’s self-caricature is sketchy and minimal, a canvas upon which impressions accumulate, but his detailed representation of architecture and infrastructure is telling. There’s the barely used subway system, possibly only servicing two stations, illumination at night reserved for portraits of the rulers, and the constant deification of the country’s leader. This was not confined just to the then-current Kim Jong-Il, but his father Kim Il-Sung, whose 1994 death was no impediment to retaining his position as North Korea’s ruler. Toward the end of the book Delisle recounts the most subversive statement he heard during two months in North Korea: “I don’t like movies here. They’re boring”.

Amid all the deprivation and oppression Delisle maintains a sardonic commentary that may seem misplaced. It should be considered, though, that Pyongyang, named after the capital city, has reached a large audience previously ignorant about life in North Korea, or only marginally aware. Would a dryer recounting not infused with his personality have succeeded as well? While Delisle is able to suppress his anger and indignation, that’s not going to be universally applicable, and the tragedy is that more than a decade later, as far as anyone knows, there has been no improvement.

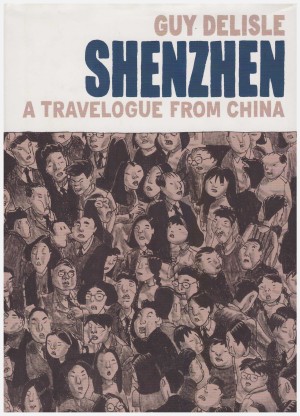

This was the first of several reportage transmissions from regimes that repress their populations, or portions thereof. See also Burma Chronicles, Jerusalem and Shenzhen.