Review by Graham Johnstone

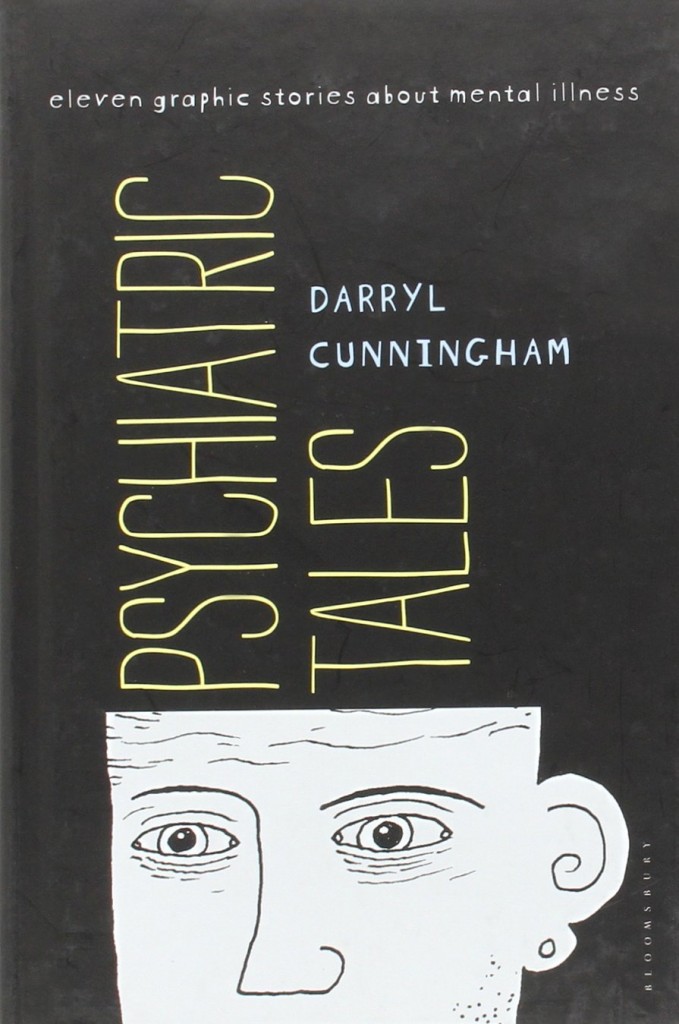

Psychiatric Tales draws on Darryl Cunningham’s experience of both working in the mental heath field, and his own struggles with mental illness. It’s an important book that powerfully illuminates conditions of which most people have little understanding. It’s no surprise that it has been critically acclaimed, and something of a crossover hit in demonstrating the power of graphic novels to deal with serious subjects.

In a series of short chapters, Cunningham talks us through different mental health conditions: depression, self harm, bipolar disorder, anti-social personality disorder and schizophrenia. He is able to talk from a theoretical perspective, while bringing it to life with (anonymised) stories of real people and situations from his working life.

Other chapters aim more broadly to raise awareness and change perceptions. ‘People with Mental Illness Enrich our Lives’ looks at some of the creative people who have creatively channelled their mental illness. Jury Garland and Nick Drake, driven by insecurities and anxieties that made them strive to be better. Their work is enriched by their powerful emotions, in the end at drastic cost to themselves. Of course the connection between creativity and mental struggles is hardly new. What may surprise people is the inclusion of Britain’s World War II Prime Minister. Winston Churchill, Darryl explains, had symptoms we now associate with Bipolar Disorder. As well as the dark moods, he had the highs of unusual energy and self belief. These qualities and his ability to cope with dark times may be what made him an unshakeable wartime leader, without whom the world might be a very different place.

Some of the material is shocking. In calm, dispassionate language Cunningham describes the ways patients have self-harmed. Cutting is most well-known, but he tells how one man repeatedly hit himself on the head with a hammer. While often thought of as primarily attention-seeking, he offers a convincing view that people hurt themselves physically as respite from even more intense mental and emotional anguish.

Often where culture has given sympathetic portraits of people with mental illness (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, for example), it’s at the expense of the staff. Cunningham, on the other hand, captures the challenges of looking after patients who are often confused as to why they are in an institution, and lashing out at the staff helping them.

This may sound like a tough read, but it’s not. Cunningham has a light touch, and wry, gentle humour. All of this only works because of his very evident understanding and compassion.

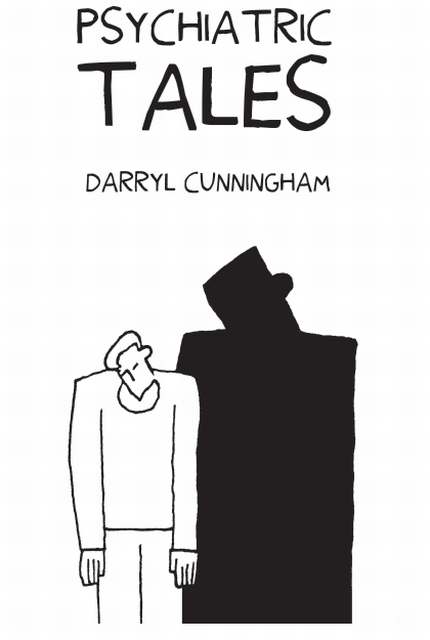

Psychiatric Tales is drawn in a minimal yet expressive style, in stark black and white. There’s a sense of urgency to tell us these important truths. Realistic rendering of these stories could both slow him down and be just too intense. His panel in ‘Cut’ with a simple drawing of a razor blade is powerful. A realistic depiction could be unnecessary, sensationalist, even voyeuristic.

He also makes smart use of found images and symbols, often as sequences of morphing images. Stripes on the Beach Boys’ shirts, become bars imprisoning Brian Wilson, their troubled leader. In ‘Schizophrenia’ a medical illustration of a brain is followed by a silhouette of a maze, then a crossword puzzle, which then breaks down into molecular images of chemicals or viruses.

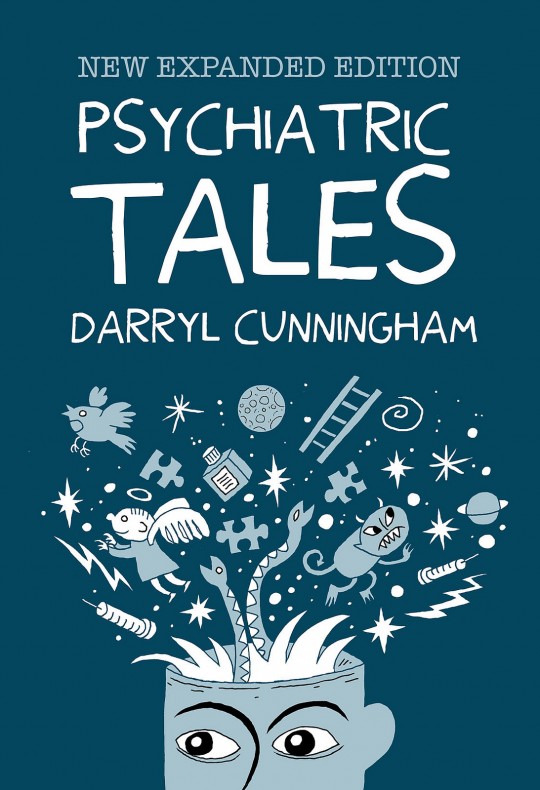

This is powerful material told by someone with uncommon insight and empathy for the subject, and the ability to powerfully communicate it in a graphic novel. The expanded edition includes additional chapters, and iconic title page images.