Review by Frank Plowright

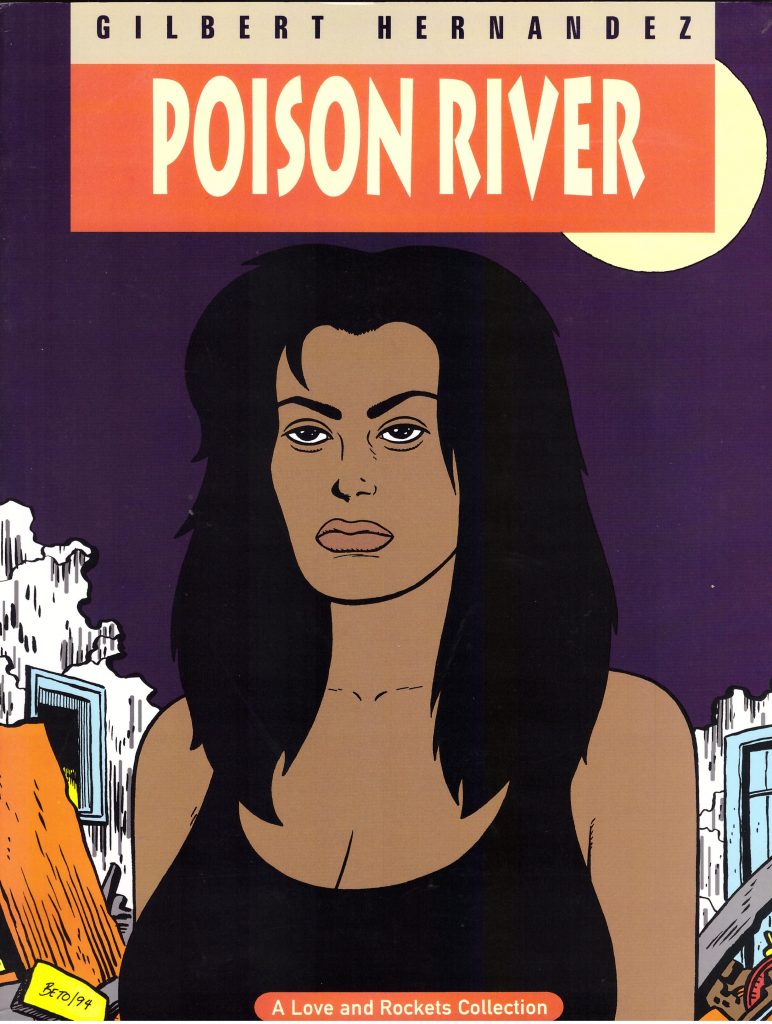

At the time he began serialising Poison River in 1989, Gilbert Hernandez probably didn’t anticipate it taking almost four years to complete what was to that point his most ambitious work. It was time well spent as Poison River remains a highpoint of a backlist brimming with quality.

Luba was already a fixture of the ‘Heartbreak Soup’ stories she came to dominate, mother to a large family, yet still alluring, and with a complex history hinted at. It’s that history laid out in Poison River, taking Luba from her infancy to her days as a gangster’s child bride and to Palomar, where she would become entrenched. Yet the densely layered story is so much more.

Hernandez’s stories featuring Luba and her community tend to build on each other, and at the time Poison River enlightened regarding previously unexplained references, but an elegant aspect is ready accessibility. This can be enjoyed by any reader entirely unfamiliar with Luba or Palomar, while those who are will pick up on small details. They’ll also be presented with a gangster story spanning the 1950s and 1960s, a story about political fear, and a story where the lives of several others entwine with significance. The horrors of rape, poverty, persecution and destitution are balanced by the joy of love and friendship in a sweeping epic. Gluing much together over the first half is the recurring motif of an unattainable past as represented by a locked box left to Luba by her mother. Readers know the significance of the individual contents, which are occasionally revealed, and the way Hernandez has others react to them is a superb touch.

It’s one among many. It might be assumed that Luba’s mother Maria becomes a narrative redundancy when she abandons her infant daughter, yet midway through the story jumps back fifteen years. Her presence then informs the relationships between others that have sustained much of the book. It’s masterful enrichment of what’s been shown beforehand,

Characters are brought to life as much by appearance as by deeds and dialogue. Apparently simple cartooning conveys great emotional depth, with the many moods of club owner Peter Rio effective in stripping him bare. 27 characters are illustrated on the back cover, all of them playing a significant role at some point, yet each of them distinct and recognisable. Hernandez additionally impresses with the variety of narrative techniques, switching between characters to escalate tension, subtle connections indicating slips back in time, and the courage to illustrate quiet moments of normality. Panels without dialogue frequently continue the story.

This is Rio’s story as much as Luba’s, and his psychological portrayal is impressively incisive as a man who can never live up to his father’s status as musician or mobster, yet manipulative and obsessed. Chapters are titled after an individual character, with Luba featuring more than most, but this is a convenience as we assimilate the cast, their needs and issues throughout, and the chapter titled after enforcer Gorgo reveals as much about others.

Adult themes feature. Luba has a voracious sexual appetite, a single aspect of her well rounded presentation, and the adult themes extend into a broader definition of the term. The allegorical rebirth, for instance, and attention required to absorb subtle but significant details that enrich proceedings. Since Poison River’s publication there have been very few graphic novels published emulating its scope, ambition, complexity and narrative competence. A significant amount of those that do are by Hernandez and his brother. A true masterpiece among graphic novels.

Poison River can still be bought individually, but is now more easily located in Beyond Palomar.