Review by Frank Plowright

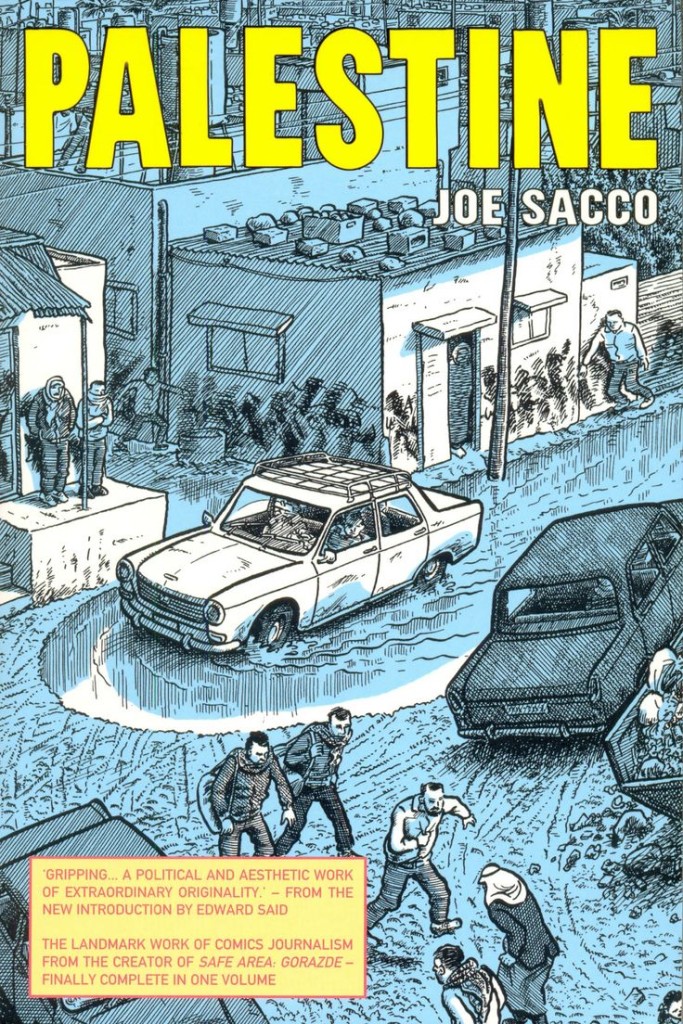

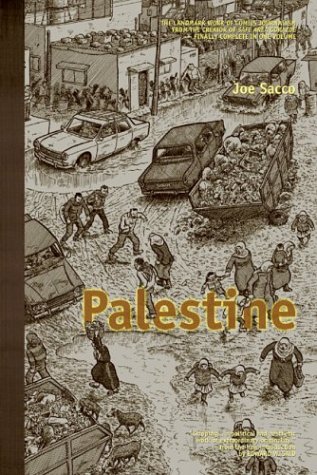

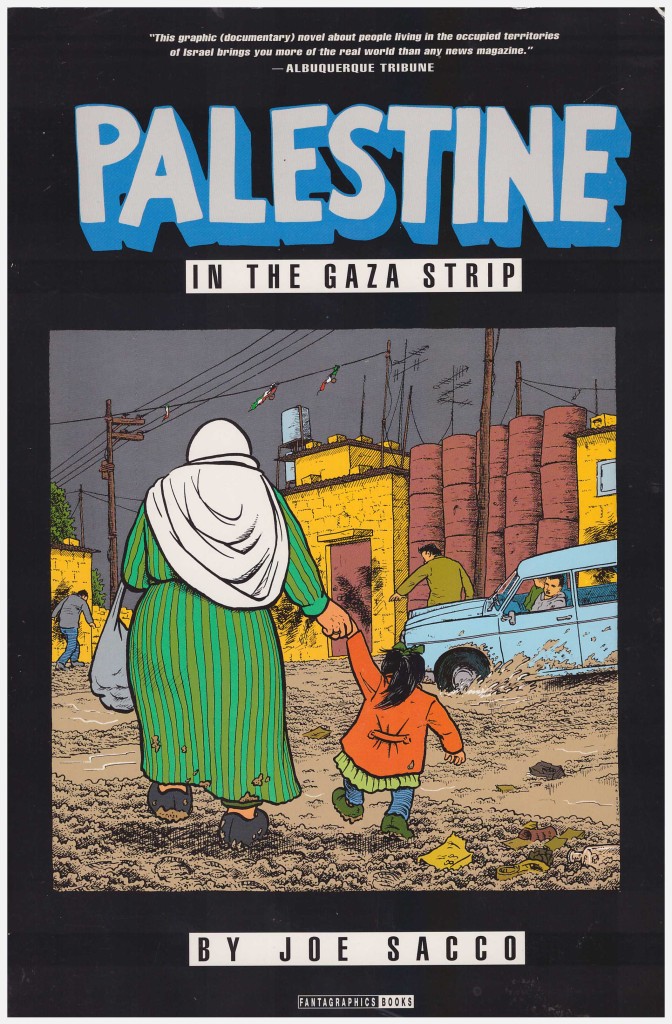

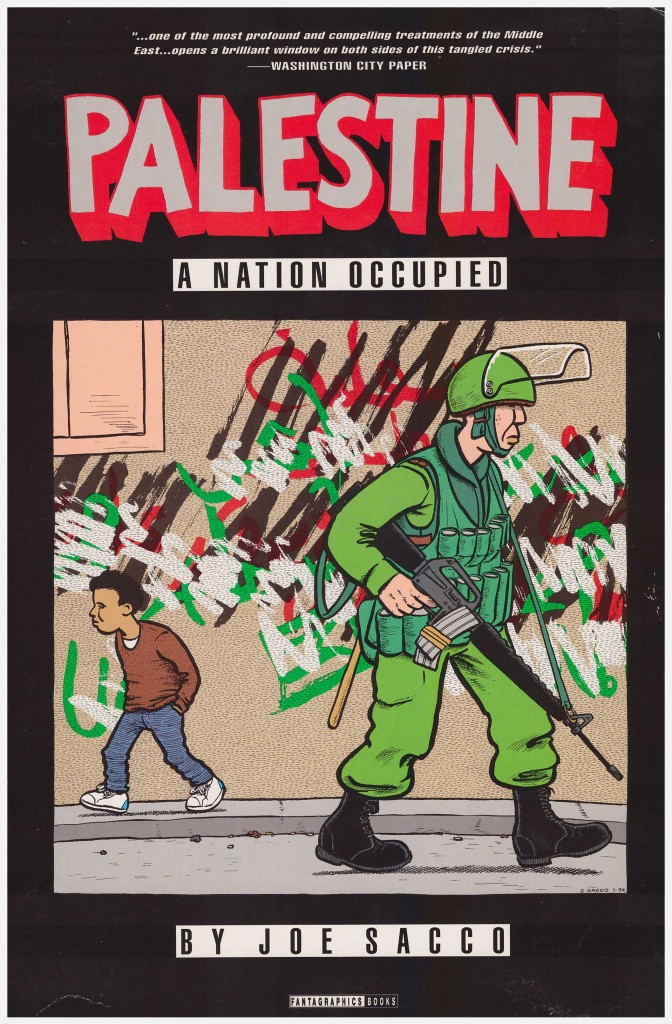

Palestine established Joe Sacco as the primary graphic novel exponent of reportage, yet it took almost a decade to achieve this seminal status. Originally published over two volumes, Sacco would frequently ask his publisher when they intended to combine them. He once received the caustic response “We could do that, or we could throw money off (Seattle landmark) the Space Needle by the bucket.” No such worries these days when Sacco is a globally syndicated creator.

In December 1991 Sacco began a two month trip to Israel, splitting his time between the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv. From that trip he documented the experiences of ordinary Palestinians he met. Distressingly, very little has changed in the years since, so Palestine remains an informative delineation of the status quo.

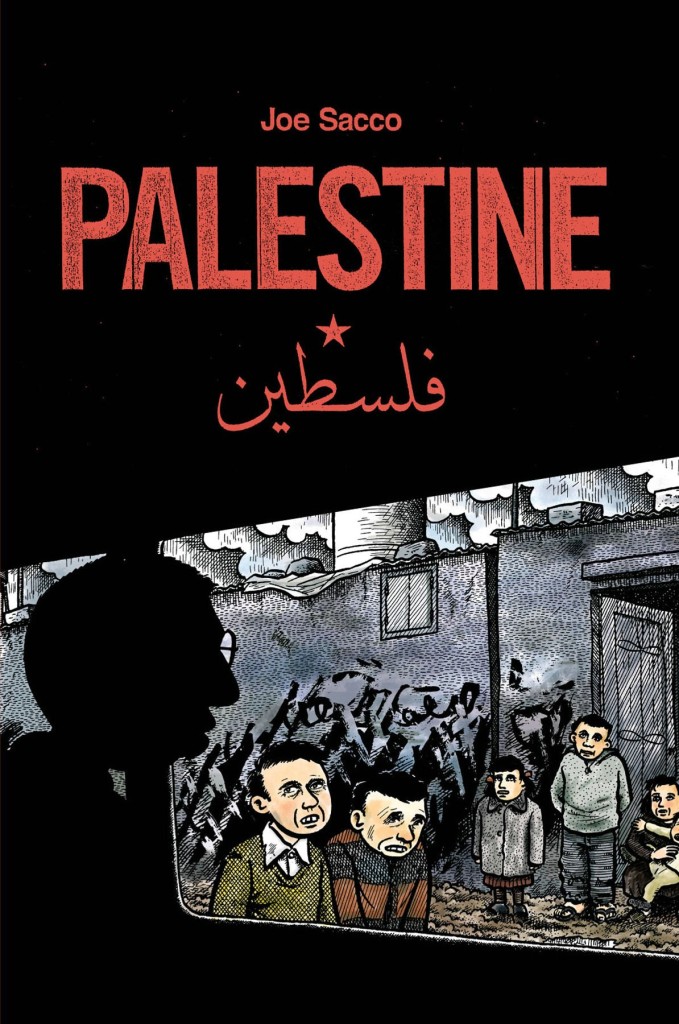

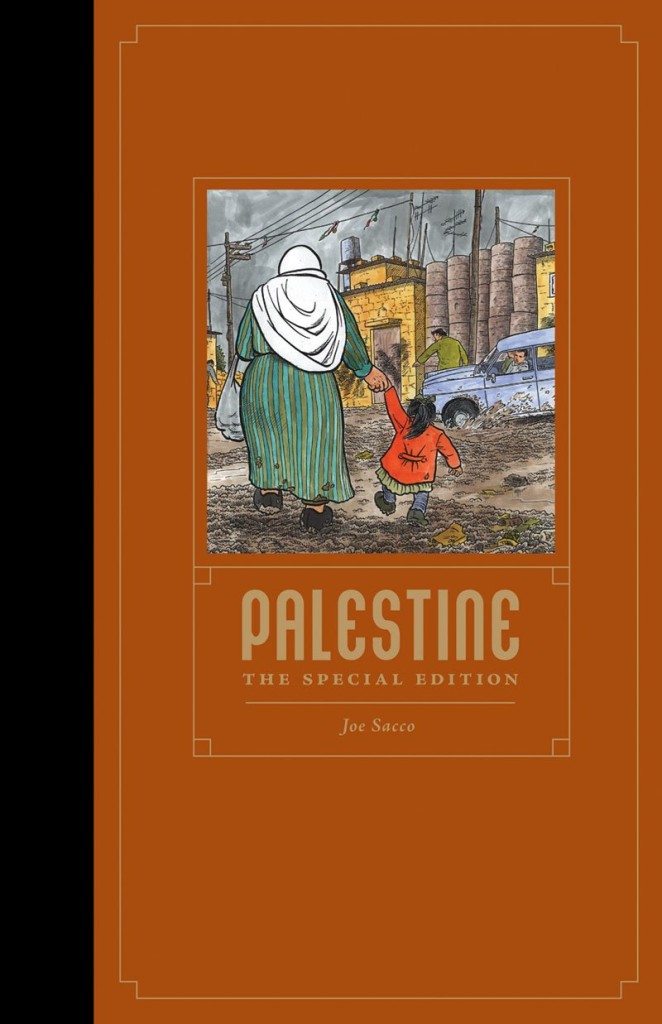

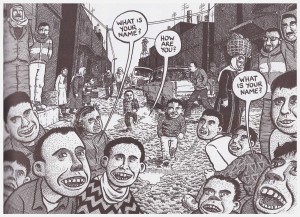

Sacco’s art is unique, and can to the casual glance be off-putting due to what may appear eccentric placement of caption panels, extremely crowded pages and his unusually gaping, wide-mouthed, toothy individuals. Look a little more closely, though, and there’s a fine graphic sensibility. The captions lead the eye, the crowds convey the chaos, and the wealth of detail Sacco provides in his fine hatched art is immense. Late in the book there’s a two page sequence set in a taxi during a storm. Sacco’s line supplies every raindrop amid a situation of escalating tension and possible danger. That alone is some achievement, and there are dozens of comparable depictions throughout.

Despite his own grotesque and unappealing caricature, Sacco comes across as likeable, thoughtful and concerned, and has the formidable strength of being able to listen. There’s a self-deprecating sequence opening the book exemplifying this, when a group of Palestinians are very grateful that anyone has taken the time to hear them. It’s simultaneously immensely and tragically prophetic about what prompts American concern. Sacco applies some of his own speculations, but the majority of Palestine is verbatim, the explanations and perceptions of others.

Collectively, it remains a catalogue of horrific state-sponsored repression in the name of national security, an echo that’s become all too expansive in the years since Palestine was experienced by Sacco. The persecution ranges from the (in context) relatively minor pettiness of depriving a community of their living by gratuitously cutting down their olive trees, to the wholesale torture of innocents. An early sequence relates the fishing expedition carried out by Israeli security forces after removing Gassam from his home in the middle of the night. He was abused for nineteen days without any evidence, the courts granting two extensions to his detainment beyond an initial 48 hour period. A third judge finally ordered his release, not accepting the mantra that more time was required to gather evidence. This is harrowing enough on an individual basis, but is a common experience.

While he attempts to understand, Sacco isn’t presenting a balanced appraisal. His intent in travelling had been to experience life as it was for Palestinians, and he notes late in the book when challenged about this that he’s heard the opposing viewpoint his entire life. Some critics consider this an abrogation of duty, as if the elsewhere available material isn’t already heavily weighted in promoting official Israeli justifications, and as if it’s Sacco’s obligation to tread the middle ground. Not doing so will therefore always devalue his achievement in their eyes. An inability to understand is an attitude that feeds into the perpetuation of horror, and Sacco’s done a fine job in humanising the complexity.