Review by Frank Plowright

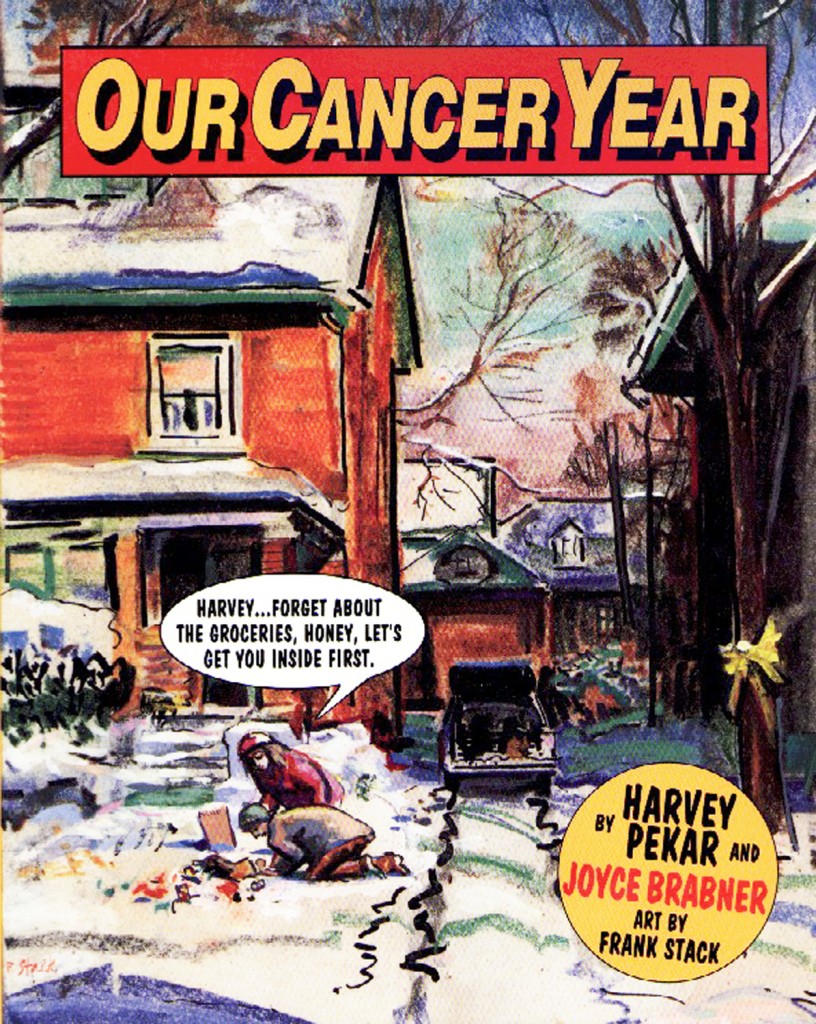

As established in his previous work, Harvey Pekar is a man who fears change, always anticipating it will be for the worse. Moving home is high on the list of stressful experiences for anyone, let alone someone with his mindset, and that’s just the prelude to a life-threatening condition. Pekar also fears illness, treatment, that his wife will leave him, that he’s being ripped-off and assorted other matters. This isn’t just his story or narrative, though, as noted by the plural in the title. Joyce Brabner equally experiences and relates what occurs for the couple during 1990.

While the major portion of the book is illness-related, the entirety is set against the backdrop of Brabner’s contacts who live in or have experienced conflict areas around the world, and the first Gulf War. She’s compiling stories for a future project, keeping in touch as an early and enthusiastic adopter of modem technology.

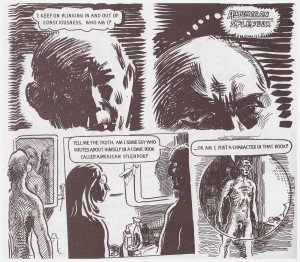

Pekar’s illness was caused by a small testicular lump that he resisted submitting to medical investigation on the basis of previous complications with surgery. When cancer is confirmed his fears accelerate into overdrive. Chemotherapy is required, and in order to minimise the period he elects for shortest possible treatment regime, not fully appreciating the toll this might take. For much of the narrative, therefore, Pekar himself is little more than a package, passed from home to hospital in varying shades of pain or discomfort, a terrifying experience sometimes heightened by the medication cocktail he’s consuming. Among these is a disturbing hallucinatory moment in which Pekar can no longer be certain he’s not just a character in the American Splendor comics he writes. The overall parallel with Brabner’s contacts surviving their own war isn’t hammered home, as she has to be the bastion of strength, dealing with awkward medical staff and Pekar’s lack of capability.

Frank Stack’s art can appear awkward, and varying his layouts for talking heads isn’t a priority, but the sketchiness is a fine choice for detailing the horrifying conditions resulting from Pekar’s body being weakened by treatment. It accentuates the other-wordly distortions of medication and the helplessness of illness. There is no sparing the reader the sheer exhausting catalogue of distress the experience forces on both parties, and as such this remains a disturbing book.

Since the publication of Our Cancer Year comics with a medical theme have experienced a boom, whether as autobiographical experience of illness or education-based. Few, however, have approached the dramatic intensity unleashed by the honesty and full spotlight prioritised here.