Review by Ian Keogh

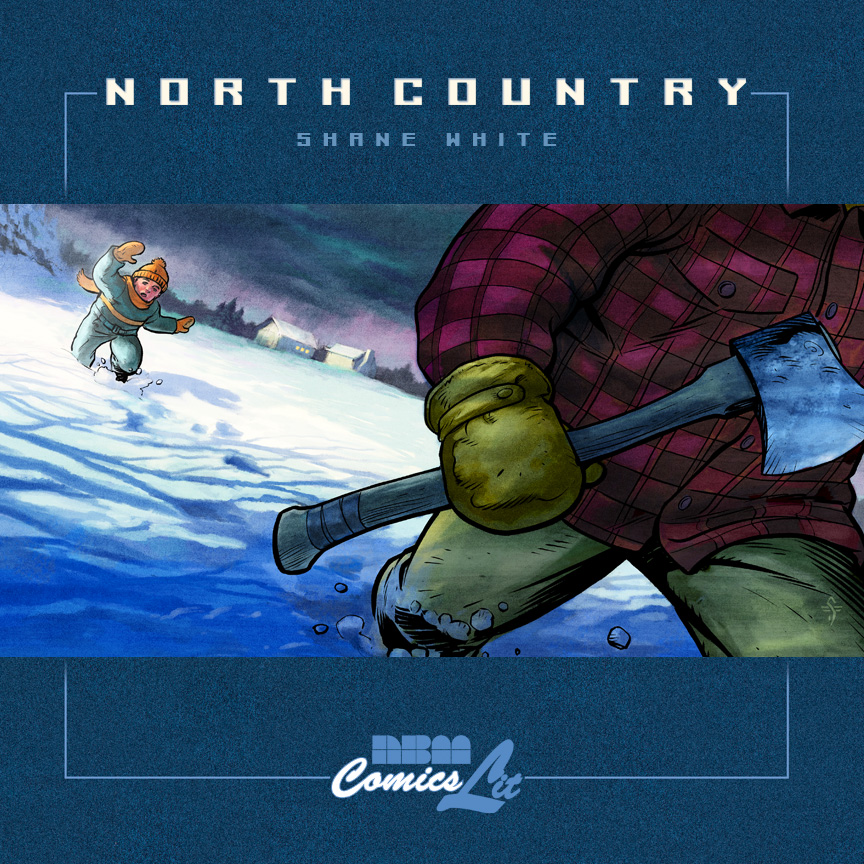

All too sadly, Shane White’s childhood living in perpetual fear of a violent and tormented father is a far from unique story, but consistently interesting visual devices transform a confessional exorcism that would otherwise perhaps best be left with the therapist.

White differentiates his work immediately via largely restricting himself to three tiers of three square panels, resulting in square pages. This formal structure expands to incorporate large illustrations for emphasis, while simultaneously reflecting the rigidity of his younger life. A sense of experimentation is expanded by an endlessly fascinating use of colour. White integrates it into his experiences as a tonal device, marking past from present, or a good experience from a bad. Some pages will be vivid brightness, others a sepia wash, and to a lesser extent this variance extends to experimenting with styles of art also.

White’s parents married young, his father already having seen service as an engineer in Vietnam, carrying a constant anger within him, fuelled by alcohol intake. White presents his younger self as always cowering, always having to consider what he says in terms of whether it will set his father off, and in one heartbreaking scene he’s injured and the recollection of what he felt isn’t pain, but elation at his father hugging him tightly and weeping. While a victim herself, his mother also rages about relatively minor incidents, and at a seventh birthday party for another child White learns that in some families the problems run even deeper.

Unhappy recollections of childhood and youth are punctuated with scenes of the adult White flying back to see his family, the air conditions as turbulent as his conflicted feelings. It’s a clever narrative trick, because as he reveals more about his childhood there’s a constant wonder about why there’s still any contact. The flight is a form of double metaphor, first as the young White treasured the possibility of flying, the act an obvious wish fulfilment, and secondly representing the long journey toward acceptance and reconciliation. Given most of the book, it’s strange to consider it could occur, and the strength of the family bond was surely tested by North Country’s publication. That White felt the need to publish it reveals some unresolved feelings, and while a door is closed on his pain and hurt, there’s never any real understanding about what formed his tyrannical father, of where the deep-seated anger originated. The younger White spending some time with grandparents indicates a quick resort to threatening physical punishment, but not to the degree that formed his father.

Ultimately what sticks in the memory as the strength of North Country is the arresting visual presentation rather than the sadness of White’s experiences.