Review by Woodrow Phoenix

In his introduction to this book, Denis Kitchen writes about the response from “all segments of the comics industry” when he began publishing collections of Nancy comics in the late 1980s: “Reactions were swift: the co-publishers of Fantagraphics thought I had lost my marbles. Ardent fans of The Spirit and Flash Gordon recoiled at Kitchen Sink also publishing ‘dumb’ Nancy strips. Retailers who stocked all our other titles expressed hesitancy to display Nancy Eats Food or How Sluggo Survives! The mere thought of adding Bums, Beatniks and Hippies to their otherwise respectable libraries evidently gave shivers to some collectors … I followed my own instincts publishing five volumes of Bushmiller’s Nancy. Despite resistance in the comic shop market, they sold in the mass market.” Fantagraphics of course saw the light 20 years later with their three volumes of Nancy reprints, but it’s taken another ten for this latest collection to arrive.

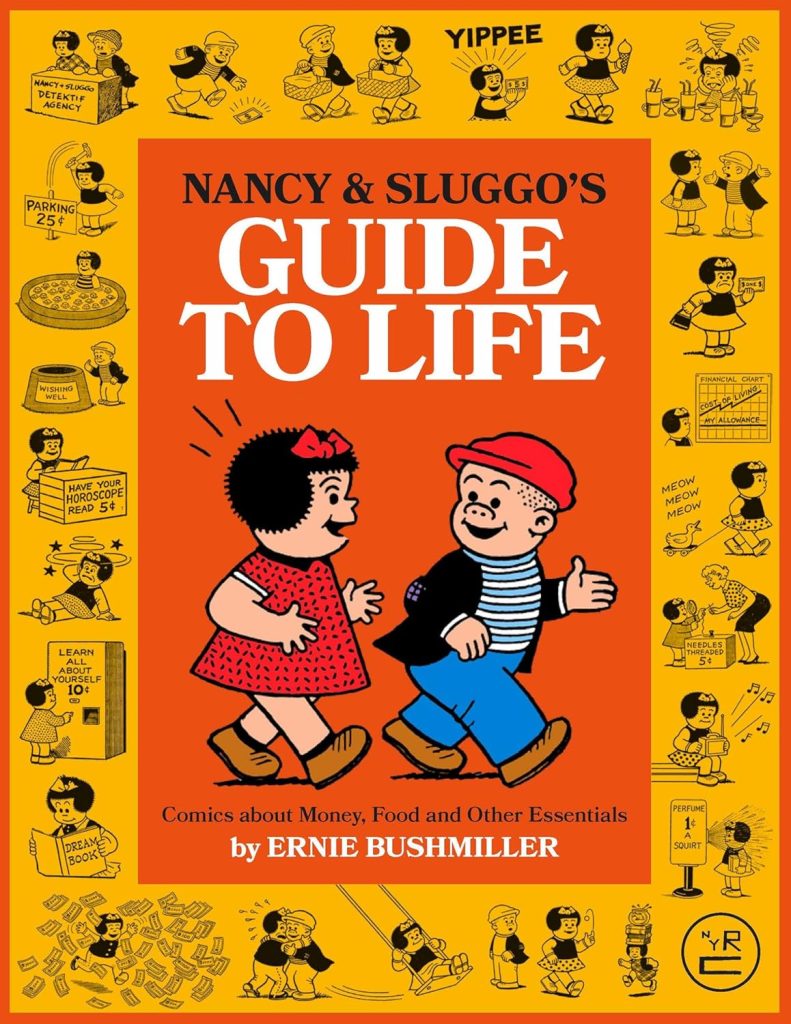

New York Review Comics publishes new editions of “out-of-print masterpieces” and Nancy and Sluggo’s Guide to Life is selections from the long out of print Kitchen Sink editions, as well as many more newly selected cartoons never reprinted before. The Fantagraphics volumes were valuable for reprinting strips in chronological order, showing how the daily ingenuity of Ernie Bushmiller’s process wrung every possible derivation from the chosen prop of the week. But they were early Nancy. There was still quite a lot of conventional narrative anchoring the strip to everyday life. The surreal and nutty jokefest was just starting to really get cooking by 1950, as Bushmiller’s drawing became more modular, more cleanly geometric, his props more symbolic and the expression of his ideas more conceptually extreme. This volume is a ‘best of’ that roams freely through all the decades of the strip, but because of the organisation of the material into categories –Money, Food, and Sleep – it all feels very coherent and the themed selections intensify the humour to hallucinogenic heights by the final pages.

The ideaspace that these comics float through so clearly reflects their time period that it’s hard to understand why ordinary readers ‘got’ Bushmiller’s approach so strongly while his contemporaries in the industry didn’t. Perhaps he was just too far ahead of the professional wisdom about what constituted appropriate style and content in the newspaper strips of his time. If you compare the brilliantly relentless escalation that’s a feature of Nancy to every other American newspaper strip of the 1950s through the 1970s there is nothing that is on the same daring and imaginative level. This book is a powerful demonstration of what comics can do conceptually, questioning the relationship between images and what they represent as no other medium can. Read it and be amazed while being thoroughly entertained.

If you aren’t the analytical type, no evaluation is required and Bushmiller would probably prefer you didn’t try anyway. Just enjoy the jokes. You’re welcome.