Review by Frank Plowright

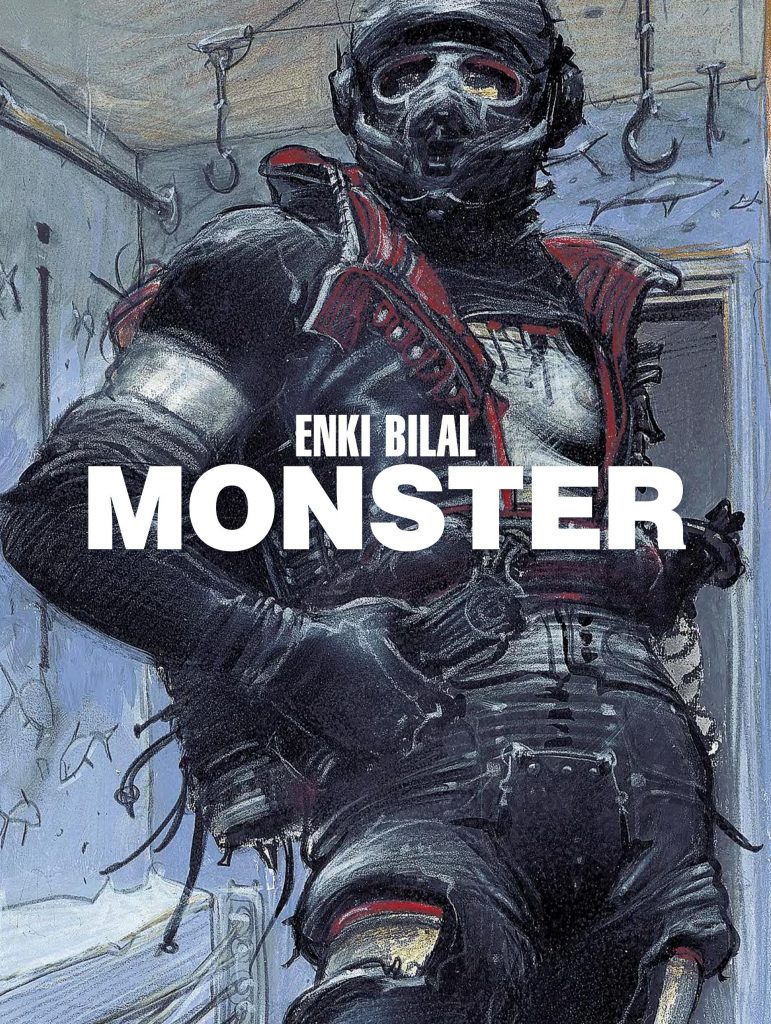

Enki Bilal is a complex storyteller, and Monster isn’t a graphic novel given to casual disclosures. Although his impressive career began in French comics, Bilal was born in Belgrade, and spent the first nine years of his life there before moving to France. Begun in 1998, the four volumes translated and combined for Monster filter the ideology of conflicts in what was the composite nation of Yugoslavia as it fractured in the early 1990s, but through science fiction notions. The world we’re introduced to is 2026, but a version Bilal knew at the time of creation would be greatly more advanced than ours on reaching that time, although he gives it a grubby, cobbled together look. Machinery such as flying cars is convoluted, as if constructed piecemeal rather than manufactured, and the skies are strung with dangling cables. This is contrasted by inordinately sophisticated artificial life and scanning devices.

We’re told there’s an ongoing war, although most people live their lives seemingly unaware that society is targeted by an extremist religious organisation whose aim is to wipe out anything considered cultural or scientific. Our perceptions of the situation are largely filtered through Nike Hatzfield, a man with almost total recall, Amir Fazlagic, and astrophysicist Leyla Mirkovic-Zohary, three people we gradually learn are connected through being subjected to experiments during their infancy. A Dr Warhole is responsible, best understood as a form of James Bond villain with art terrorism his speciality, and it’s only when he’s introduced that Bilal begins to connect the seemingly disassociated events beforehand.

However, this isn’t Bilal providing full disclosure for a conceptually dense story with touches of surrealism, twisting and incredibly complicated while defying adequate summary. A flavour would be to reveal Nike’s initial purpose as investigating his own death, with his captions being memories from the earliest days of his life. Who the monster of the title is shifts through several perceptions, and perhaps it’s every one of them.

Bilal takes an extremely illustrative approach to the art, telling his story via individual pictures rather than motion sequences, and frequently as text and illustration instead of conventional comics. His people and world building are phenomenal, and unless specifically arranged otherwise, the grey of decay overwhelms.

When the opening chapters were issued in English as The Dormant Beast and The Beast Trilogy there was hope of a revelation to come among all the indulgence, but it doesn’t manifest. Monster is intended as an immersive experience, and there’s a theme of artistic anarchy, which means that little becomes clearer as the story continues. Bilal has a formidable reputation, and no-one would spend a decade on four volumes for the sole purpose of disorienting an audience, but the constant procession of surreal asides eventually proves too wearing. When the basis of the story is that nothing that’s seen or heard can be trusted and so many suppositions readers are led toward prove false, the only point of seeing it through to the end is the art and the occasional admiration at an intriguing concept. Anyone finding any greater revelation and satisfaction is blessed with infinite patience.