Review by Ian Keogh

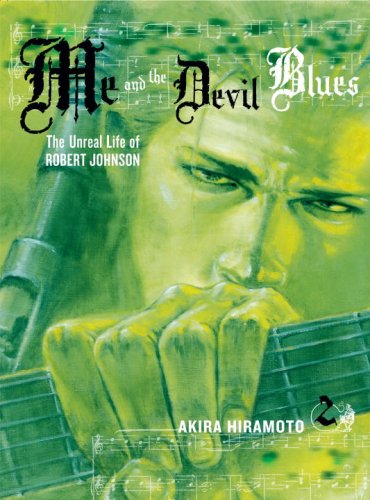

What began as a reimagining of the legend of Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil in return for his prodigious talent on the blues guitar in volume one, progressed into a wider investigation of the problems besetting depression era America.

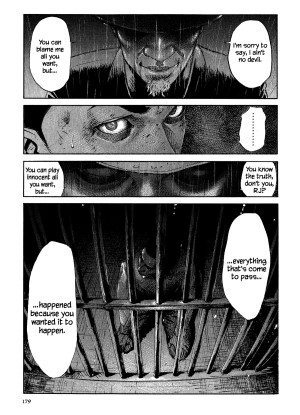

Akira Hiramoto’s main protagonist is RJ, now has his talent embedded at terrible cost, but also has an excess of fingers, and is in jail with the possibility of a lynching at the weekend. He’s been in the company of Clyde Barrow, not then notorious, in a town that’s maintained a strict no-alcohol policy by executing anyone caught imbibing.

At times in the first volume Hiramoto set a seat squirming tension, and achieves the unlikely by escalating that mood, but it’s at a price. While RJ is threatened in his cell, Barrow, masquerading as a journalist, is being entertained by the town’s patriarch who readily hints at his repulsive proclivities. As if that wasn’t danger enough, a senseless crime in the first volume is now revealed to have unimagined consequences.

The concluding half of Me and the Devil Blues starts propelled by a pair of conjoined mysteries with a side helping of philosophical discussions about desire and its consequences. It’s exceptionally well drawn, dripping with tension, and the episodes continue to be named after Robert Johnson recordings. For all that, it’s far more conventional and not as effective as the first volume. We’ve moved from deals with the devil and social iniquity with a constant musical soundtrack to a certainly suspenseful and creepy crime thriller, but one lacking any undertone other than mood. It’s also taken at a far more languid pace, and for all the southern gothic tropes, without Hiramoto’s remarkable art, both in terms of layout and dark style, this could have dragged.

We do have that art, though, and it’s magnificent. As with the first book it’s worth paying attention to the detail as it contributes greatly to character and atmosphere, and as with the first book Hiramoto’s cinematic eye creates an astounding number of memorable images. There’s surely a lot of visual reference involved, but by the time Hiramoto’s slathered black ink onto the page you’d not know. It’s worth speculating whether he took his pens down to the crossroads one moonlit night.

There’s rather an odd, but very effective concluding chapter, and that’s where Hiramoto ended his work for a number of years. In 2014, however, he resumed serialisation in Japan.