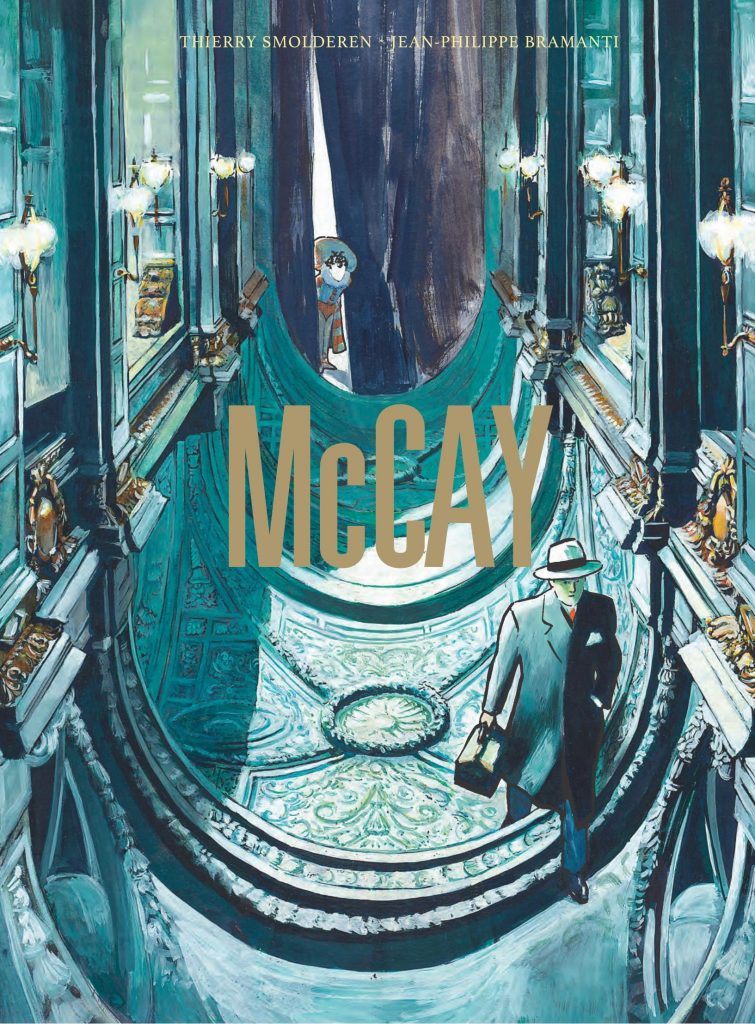

Review by Frank Plowright

In Europe, although not yet common, graphic novel biographies of renowned comic creators are hardly unknown, with more issued every year. It was only a matter of time, therefore, before someone tackled one of the founding fathers of the American newspaper strip, Winsor McCay. However, come to this expecting the strictly biographical and disappointment awaits.

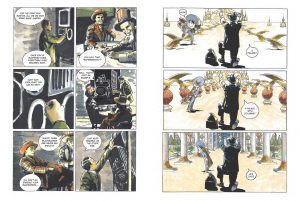

How closely the biographical material matches the subject’s own style is an important decision. While not founded in logic, as with biographies of fine artists, there may be an audience expectation that the illustrations resemble those of the subject, which discounts that part of the reason for their fame was being able to do what no-one else could. With fine artists the decision is easier by virtue of some styles just being plain unsuitable, but Jean-Philippe Bramanti’s choice is to set McCay deep within his era. He evokes the past as another country via illustrations that blur, as if slightly out of focus, and depicting scenes in muted shades, the sepia we’re familiar with from ancient photographs and darker greens and oranges. It creates an impressionistic world, but one that’s drab, only really coming to life when the script forces Bramanti to merge McCay’s day to day world with his creations.

Four French albums are combined and translated by Edward Gauvin for this English edition, and writer Thierry Smolderen starts strongly in presenting the learning McCay rather than the visionary creator, taking us on an early tour of influences that might have shaped McCay’s artistic approach. Scenes suggest why he prioritised trickery and wonder, and an unsettling experience, before a substantial narrative jump ahead to a successful McCay in his pomp. However, this isn’t a story where you’ll learn about McCay and what he achieved, but one where those already familiar with the background detail will be able to nod sagely as Smolderen constructs a fiction around them.

McCay was a titan straddling two artistic disciplines, bringing his prodigious artistic skill to bear on animation in addition to comics, yet beyond suggesting possible influences, Smolderin never develops McCay as a person. He’s a passive observer of events, some of which he later channels into his work, and Smolderen speculates, weaving possibility into truth, echoing McCay’s strips. It results, however, in an unsatisfying neither fish nor fowl work, extended by developing a fanciful drama around a series of suspicious deaths tied into people familiar with the fourth dimension and how to access it. McCay becomes a desperate troubleshooter instead of being presented as a visionary creator. Smolderen compounds matters by consigning background research that may have interested readers to his French publisher’s website. Really? There’s room for an interesting series of 24 faux dramatised covers presented as if McCay had been broken down into serialised issues, but not a couple of pages for the research?

This form of magical extrapolation around a historical figure has successful precedents. Glen David Gold’s novel Carter Beats the Devil is a satisfying example, but Carter is a sympathetic character whose concerns we know, whereas McCay is a passionless cipher. His achievements are rendered meaningless and it what’s left may as well have been about any fictional construct. The ambition is towering, but the reality belly flops.