Review by Frank Plowright

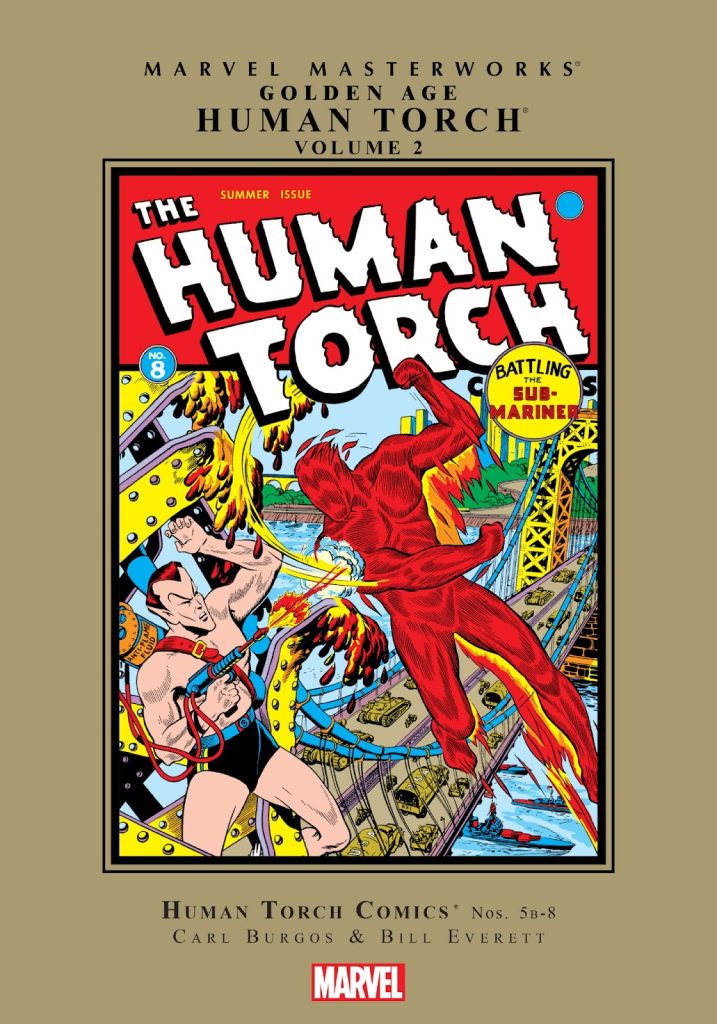

As seen in the first Human Torch Masterworks, Marvel’s convention of having guest stars began earlier than many might have thought. Maybe Captain America’s origin is more fondly remembered than the epic sixty page battle between the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner when it comes to Marvel’s 1940s output, but then it’s been reprinted or reformatted so often.

Roy Thomas’ introduction considers this opening extravaganza is very likely to be the strip Bill Everett told him was sixty pages written and drawn by multiple creators over a weekend. Jim Steranko’s History of Comics leaves no uncertainty. Apparently word went out to assorted writers and artists who gathered at Everett’s apartment. He and Human Torch creator Carl Burgos turned out the opening pages, much of the remaining plotting was handled by John Compton and Jack Darcy, with scripting handled by George Kapitan and Harry Chapman with Joey Piazza writing in the bathtub! Everett recalled artists Mike Roy and Harry Sahle involved with layouts, pencilling and inking.

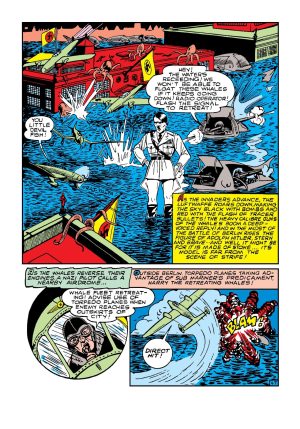

It reads as chaotically as its creation, with wild swerves in the plot, which involves Atlantis sick of the impact of sea battles between Germany and Russia and the Sub-Mariner deciding he’ll take over the world to stop them. The Human Torch must stop him. What it still has going for it is the sheer energy generated by all those creators knocking back the beer, and an enjoyable unpredictability, and to be fair to whoever came up with it, there is some logic revealed at the end.

The team-up was a massive success, and so reprised for the final story, but this time without Burgos or Everett contributing, both by 1942 part of the US military. Ray Gill and Mickey Spillane, yes, that Mickey Spillane are credited with the writing, but with this as with some Human Torch solos, there’s little indication of the jolt he’d give crime fiction a few years later, although he introduces the novelty of a crook in a flameproof suit. It’s noticeable that by 1941 the Torch is more likely to employ flame-based tricks rather than wade in with his fists, which makes more sense, and this second Human Torch vs Sub-Mariner battle gives them a foe worthy of their powers in the Nazi agent Python. This time it’s the Torch who becomes the bad guy via convenient scientific jiggery pokery. Again, energy levels are high, twists are many and while it doesn’t have the sheer nuttiness of the first battle, it’s spirited. Several artists are involved and the packed spread ending the fourth chapter resembles a bored 1960s schoolboy’s exercise book illustration.

By midway through this collection Pearl Harbour has occurred in the real world, so Japanese military or spies feature in most Human Torch and Sub-Mariner stories thereafter. While not as bad as other comics of the era, they feature racist assumptions, caricatures and phrases.

Mention should also be made of Ray Houlihan’s Tubby and Tack one page gag strips. To say Little Lulu is an influence understates the case, with the first strip a clubhouse gag, but the cartooning is tidy and attractive, bringing Frank King to mind. Art Gates’ Swoopy the Fearless is a more ordinary aerial farce, but this collection ends with a page by Basil Wolverton.

Time has moved on, so these stories are of greater interest to historians than readers, energetic but little more. Another selection follows in Volume 3. Alternatively all the Torch’s 1940s appearances are combined in the Golden Age Human Torch Omnibus.

Thanks to the Grand Comics Database for updated credits.