Review by Frank Plowright

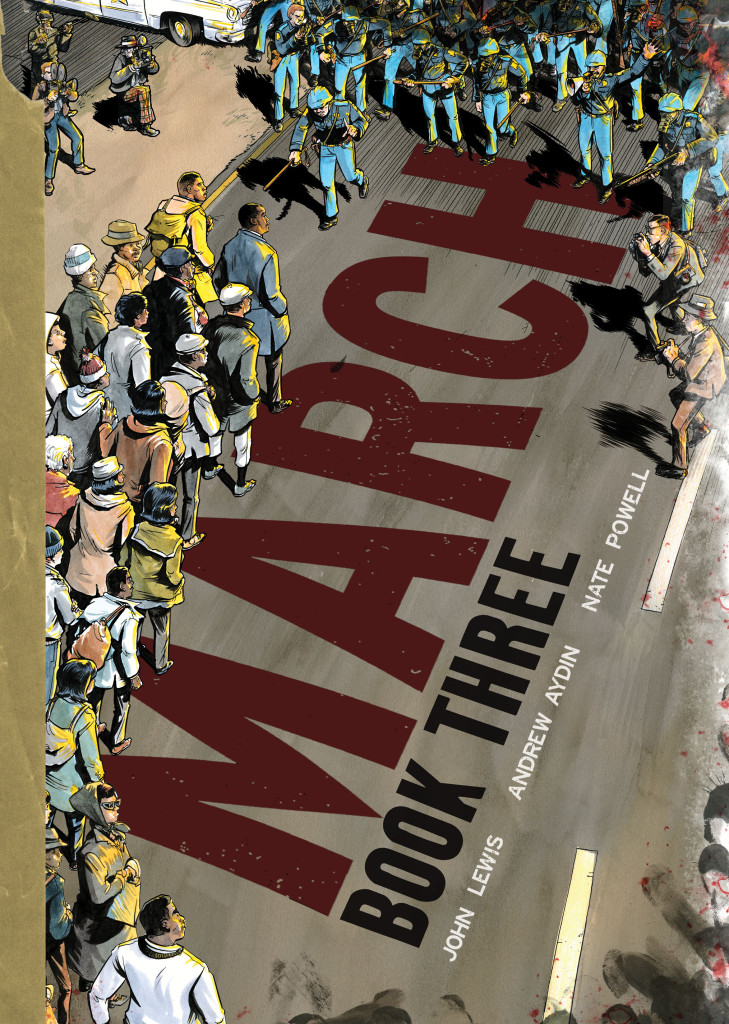

The 1963 March on Washington after which Senator John Lewis has titled his three part graphic novel memoir occurred in the final third of Book Two. It was triumphant, successful and a historical milestone. Unfortunately, not every US citizen was prepared to accept the idea of integration, and the horrific consequences of that open this book.

Donald Trump is currently a divisive presence, but let’s not forget that arch-segregationist George Wallace also ran for President, and the Alabama senator considered himself a Democrat. His aggressive bigoted proclamations fed into the mood permitting innocents to be murdered, while black citizens were denied a vote. In September 1963 Lewis and others brought their doctrine of non-violent protest to the town of Selma, which became another civil rights battleground. Here the ability of black voters to be registered was negated by ridiculous questions requiring a correct answer. An applicant unable to identify the number of bubbles in a soap bar was rejected.

The opening fifty pages cover three months in 1963, combining as a catalogue of atrocities and indignities, illustrated by Nate Powell in extraordinarily restrained fashion. Powell isn’t as accomplished with likenesses of the well known. Whereas this was of little consequence in the previous books, here we have full page portraits of Presidents and presidential candidates that would be unrecognisable without their names appended. Otherwise it’s business as usual for him, with lively illustrations conveying the spirit of the times.

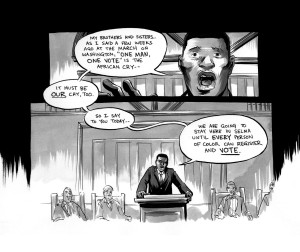

It’s a job made more difficult for Powell by Lewis and his co-writer Andrew Aydin providing frequent scenes of political discussion at meetings. These require innumerable talking heads, and slow the book down more than its predecessors, their frequency testament to both Lewis’ increased standing, and a tendency to present a discussion covering conflicting views when a single line statement would suffice. These are details of historical importance, but surely related elsewhere, and the requirements of a graphic novel differ from a book relying solely on text. It leads to long sections with a drier tone throughout. The same applies to the number of speeches quoted in some detail over several pages.

Collectively these sequences exemplify arguments on any kind of progress, splitting campaigners between those accepting small steps and those considering this method too slow. Lewis was among the latter and his own story is crucial to the tenor of the times, and fundamental to those events.

The final section returns to the opening pages of the first March book, and a second march, this in 1965 from Selma to Montgomery in Mississippi, and of even greater relevance. The book concludes with a victory of sorts, but as events of the 21st century display, the preposterous stain of hating someone merely because the colour of their skin differs has never disappeared, despite Lewis rising all the way to Washington.

Collectively March is a crowning achievement recording tumultuous times deserving of a far wider audience, yet this conclusion, encompassing the events of greatest historical significance, isn’t as engaging. It’s both more episodic and less effectively paced. We should, however, be grateful both it and Lewis are with us.