Review by Allen Rubinstein

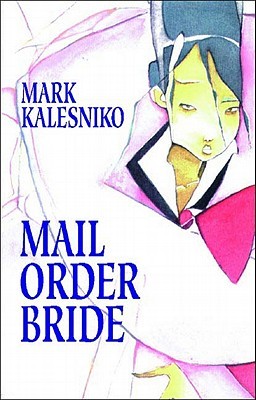

There must be something to the idea of an artist exorcising his or her demons through their work. Mark Kalesniko, himself a cheerful, sociable Canadian, has written and drawn some of the darkest, most acidic graphic novels you’ll find. Known for a trio of books featuring the alcoholic, dog-headed animator Alex, his best work is 2001’s Mail Order Bride, a multi-layered study of isolation and cowardice, cultural clash, racism as it expresses in sexual fantasy and marriage as a mutual life sentence.

True to its title, Monty Wheeler arrives at the airport for the Korean wife he “ordered” from an ad in a magazine. The ad promises women who are “traditional, obedient, exotic, domestic, simple girls” and can apparently employ, “Asian sex secrets.” Instead, Monty meets Kyong Seo, a woman in Western dress who has no Korean accent, isn’t good at math and won’t reveal anything about her past. Monty spends the first weeks of their marriage trying to hem Kyong into his idea of what Asian women are supposed to be like.

The irony is that Monty is the quintessential stereotyped geek. He owns the local comics and toy shop, the customer base of which is entirely selfish, bratty adolescents. His home (their home) is piled high with his personal toy collection, and his social life consists of only old people, Monty being threatened by anyone who strikes him as one of “the cool kids”. Even worse, and this is the piece overstepping by a wide margin, Monty is an uptight 39-year-old virgin before Kyong takes the initiative to consummate their marriage. As trite as the Monty character is, it’s plainly Kalesniko’s strategy to make the reader side against this pathetic character before he can pull the rug out from under expectations.

In the meantime, Kyong blossoms. Chafing under the stultifying life Monty has imagined for them, she befriends an Americanized Asian woman and a group of hippie artists while finding an affinity for nude modeling, all of which pushes Monty into petulant resistance. Kyong goes from sweetly asking permission, to secret rebellion to open rebellion as she loses respect for the, “Wimp, geek, coward,” with whom she’s so clearly incompatible.

Or is she? In its final act, Mail Order Bride explores the extent to which they are both fleeing from reality, too afraid to face life on its terms. In their final confrontation, Monty shouts to her, “I know who I am! Who are you?” While Kyong may not live up to the subservient sex kittens from Monty’s Asian porn collection, her reasons for wanting to be a mail order bride, trading in her status for security, may be as suspect as his use of the racist institution.

Kalesniko draws this bitter battle of the sexes with a scratchy thin-line energy. He’s superb at silent moments and timing close-ups and reaction shots to convey complex emotions – resentment, embarrassment, contempt, awkwardness, broadening awareness. When their conflict becomes physical, his art roughens up right with them, a visceral depiction of real violence. Mail Order Bride marries form to content in astute and skillful ways.

Those who have reacted negatively to Monty’s stack of geek clichés may be missing Kalesniko’s purpose – exploring the temptation to reduce people to cultural and racial types whether the individual fits the bill or doesn’t. In Mail Order Bride, Kalnesniko has created a rich, adult graphic novel that specifically references the culture of the comics world to throw racist attitudes into a fresh light. It’s a daring approach and largely a successful one.