Review by Jack Kibble-White

Chester Brown creates nonchalantly brilliant comics books. His first ongoing series, Yummy Fur, featured a free-flowing ongoing strip called ‘Ed the Happy Clown’, before the title evolved into an autobiographical account of the cartoonist’s formative years. At a time when alternative comic books were chock full of true life stories of this type, Brown’s work stood out for its lyricism and ability to find profundity within its confessional subject matter.

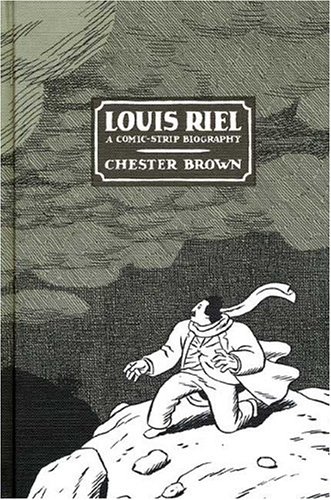

Seemingly growing tired of autobiography, Brown diverted into something stranger with his, eventually abandoned, series Underwater, before turning his clear-headed, dispassionate style to something different – a biography of Canadian politician Louis Riel. Originally serialised in comic form over four years, the collection of these ten issues into a single volume is by far the best way to experience the initially perfunctory feeling Louis Riel.

The characters speak in pure exposition, and the economy of Brown’s storytelling is such that the negotiation and eventual sale to the Canadian Government of Rupert’s Land (a territory in British North America) is accounted for in just four panels. Similarly, the eponymous character’s conversion from ordinary Red River settlement inhabitant to political leader of the Métis people takes less than two pages.

Louis Riel is an oddly bloodless book, particularly given it covers a particularly violent period in the early history of Canada. Its characters all somehow come across as miniature people racing across a dioramic landscape. No head ever fills the frame. Brown places us in a God-like position, encouraging us not to make human connections with the unfolding story, but to find a sense of absorption through omniscient observation.

In serialised form the effect is unsuccessful, but in this collected version, Brown’s aesthetic works brilliantly. His simplistic, old-fashioned cartooning style (which many have referenced as being reminiscent of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie) washes away any surface charisma that Riel might have had in real life, but ultimately elevates him, by showing that his political accomplishments still stand up even when told in such as stylistically reduced way.

The artwork, although simplistic, does still demonstrate Brown’s virtuosity with ink. Beautiful, understated cross-hatching crops up all over the place and the artist has a wonderful way with an aerial view. His is an unflinching eye, and his account of Riel’s fate is all the more affecting for its perfunctory telling.