Review by Ian Keogh

Red Letter Day is a clever graphic novel, with plenty of signifiers indicating it’s for young children from the simple, expressive characters, to the stream of consciousness whimsy that often comes to nothing. Yet it also hovers on the edge of meaning, as if Metaphrog are allegorically commenting on something beyond the obvious futility of so much common employment. Perhaps best to take it at face value rather than perform intellectual contortions.

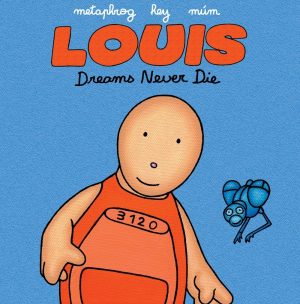

Louis works at home, buzzers clocking him on and off and indicating which of several tasks he’s to undertake. Is he going to be inflating vegetables, or filling bottles with air via machinery installed in his house? Other sinister manifestations of technology include a machine labelled as a comforter that delivers positive homilies as suggestions via cards, and a massive television, the entertainment centre it’s suggested Louis watch more often. He has a companion he loves, FC, a form of mechanical bird in a distinctive cage that sings to him, the initials a contraction of ‘formulaic companion’. Louis is being monitored by his neighbours, one of whom masquerades as a postman delivering him letters from a previously unknown Aunt Alison. Louis writes back, and receives further fraudulent responses. It’s all very sinister, a form of 1984 for children, but the sting is taken by Louis having an inordinately positive personality, if not being the brightest, and the wonderful simplicity of the cartooning.

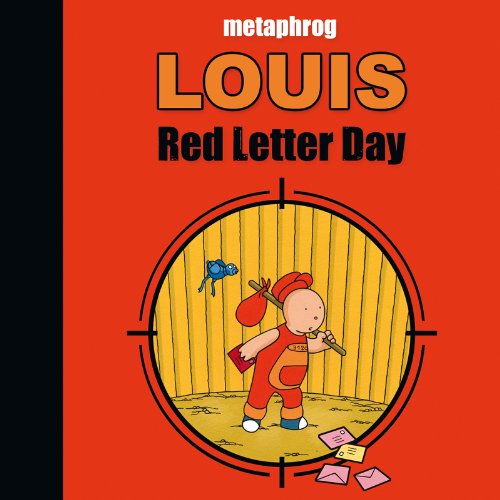

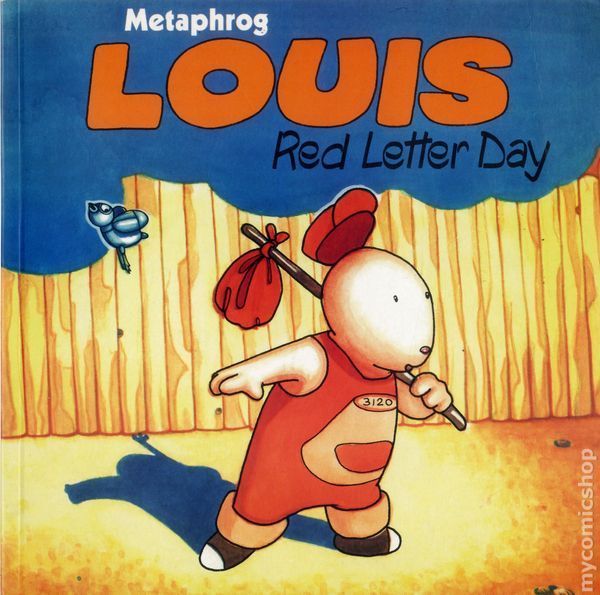

Metaphrog is the combined alias for Scottish writer John Chalmers and French artist Sandra Marrs, who have produced two versions of Red Letter Day. As seen by the comparison sample art, with muted colouring and differences to the layouts, the original 2000 publication was a far more ambiguous construction, the mood closer to anti-Soviet animation of the 1960s in which individual spirit was always crushed by the state. That the original version was ever marketed as a children’s book almost beggars belief. The 2016 reissue looks far more inviting, the cartooning simplified, the colouring more vivid, and Louis more cheerful with his lot. He still yearns for something more than his daily drudgery, however, and that spirit is fed by a mysterious visitor.

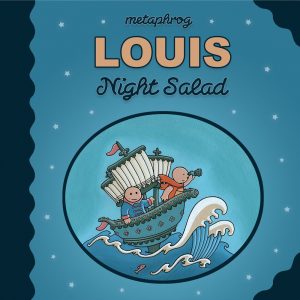

Dreams are important to Louis, several of them illustrated, as an expression of the freedom he eventually strives for, and the whole of Red Letter Day has a dreamlike quality, embracing the surreal and the ridiculous. Louis is involved in strange situations that lose their sinister overtones when embraced by the younger mind, so the original edition touched a nerve, and was followed by four sequels, each of them moving closer to the bright and simple cartooning of the revised edition. Although there is no continuity as such, Lying to Clive followed this story.