Review by Graham Johnstone

Amy is a few years out of college, her creative dreams fading, and wondering is this it? She works in a clothes store, but (as one guy backhanded-compliments) isn’t “too bent on fashion and [looking] great”. She’s sick of her boyfriend, but does she even have the will to end it?

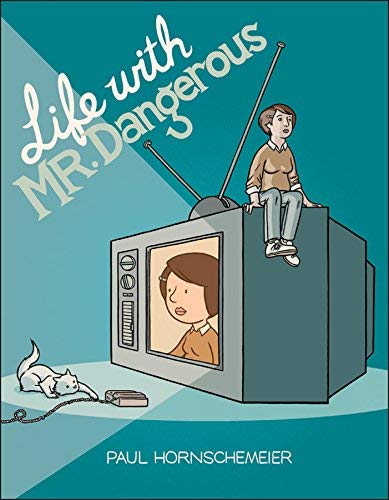

Hornschemeier engagingly takes us on Amy’s journey, her thoughts seeming heavily narrated at first as she gripes about her mom, and the guy on the bus “looking right at my breasts”, but the captions are revealed as her talking on the phone. Smartly, we only hear her side of the call. We’re not told who she’s talking to: “did you ask her out?” Not a romantic prospect then? The person on the phone turns out to be Michael, a college kindred spirit turned long-distance confidant. So far so normal, so why would we want to read this?

Hornschemeier draws this with a realism that fits the story. He may take reference photographs, (as his avatar does in The Three Paradoxes), but his artistry turns this seamlessly into comics’ traditional brush lines and flat colours. He creates a vivid staging, captured in lingering cinematography as a page of Amy, just walking through a mall, turns routine into art. It conjures the world and leaves space for the reader to enter. The ice cream parlour scene is a highlight, being all pastels, bar the gaudy cartoon posters. The ice cream is poised to melt off the spoon, some sprinkles dragged with it. The eligible server wears a bubble-gum tinted shirt, and the rainbow in a background poster always seems to radiate from him.

Hornschemeier as writer, captures equally vivid details. Amy’s birthday gift from mom is a fuchsia pink top, with a cute unicorn. Amy and Michael share their love of the Mr Dangerous cartoon, and make and send each other toy figurines, including the show’s ‘anti-matter twins’. Hornschemeier shuns the over-dramatic, exemplified when Amy is called into the manager’s office, and the less conflictual outcome is more satisfying. The mundanity is itself vivid. After going home with a guy, they stand side by side, in states of de-sexed undress, brushing their teeth, and moments of comic irony come as a surprise: “I slept with the ice-cream man. OK?!” He keeps a fresh toothbrush for post-parlour sleepovers: he plies the sweet treats with social responsibility. So why does she refuse him her number? There’s no plot-twist ending, but when we see Amy squeezed into the unicorn top, it indicates a turn.

The TV cartoon scenes add visual variety and the ‘anti-matter twins’ metaphorically represent Amy and Michael. The titular ‘Mr Dangerous’? Perhaps just an ironic comment on what she’s looking for. The initial ‘Amy Theatre’ montage of exes provides economical backstory, though some scenes over-explain present actions. However, any such issues are minor.

In the 2000s, Chris Ware, was such a powerful influence as to be almost invisible – with hindsight, it’s obvious here: in the realism, the glacial pace, the contained emotions, and the enduringly resonant childhood iconography. Is it similarly semi-autobiographical? Possibly, with a distancing gender switch? Or perhaps the author surrogate is Michael, piecing together Amy’s life from the log-distance calls… ? In any event it’s an engaging read. Like ice-cream, and unlike Ware, you’ll be tempted to consume it in a single sitting.