Review by Frank Plowright

Between the two world wars the poorer areas of Paris were home to some of the greatest creative minds of the 20th century, both European and American. At their centre of their community, as muse and object of lust and love, was a young woman who called herself Kiki.

Born in 1901 and christened Alice Prin, her rural fatherless childhood was spent in poverty. She led a dissolute lifestyle from a very early age, and there’s a sad circular pattern to her life. When 12 she moved to Paris to be with her mother, and five years later was left homeless when her mother objected to her modelling naked for a sculptor.

From that wretched point Alice re-invented herself, made connections, and within three years she was the toast of the Parisian artistic community and well on the way to achieving the Queen of Montparnasse status engraved on her tombstone.

There’s often the biographical temptation to retroactively apply greater status to free spirits, so it’s encouraging to note that José-Luis Bocquet’s well researched script makes no claim for Kiki as a symbolic model of emancipation. She’s presented, in very engaging fashion, as a woman who knew how to enjoy herself, and whose early experiences taught her the dangers of being dependent on others. Neither is this a whitewash. Kiki’s attraction to beauty led to several wrong-headed decisions, not least when it came to relationships.

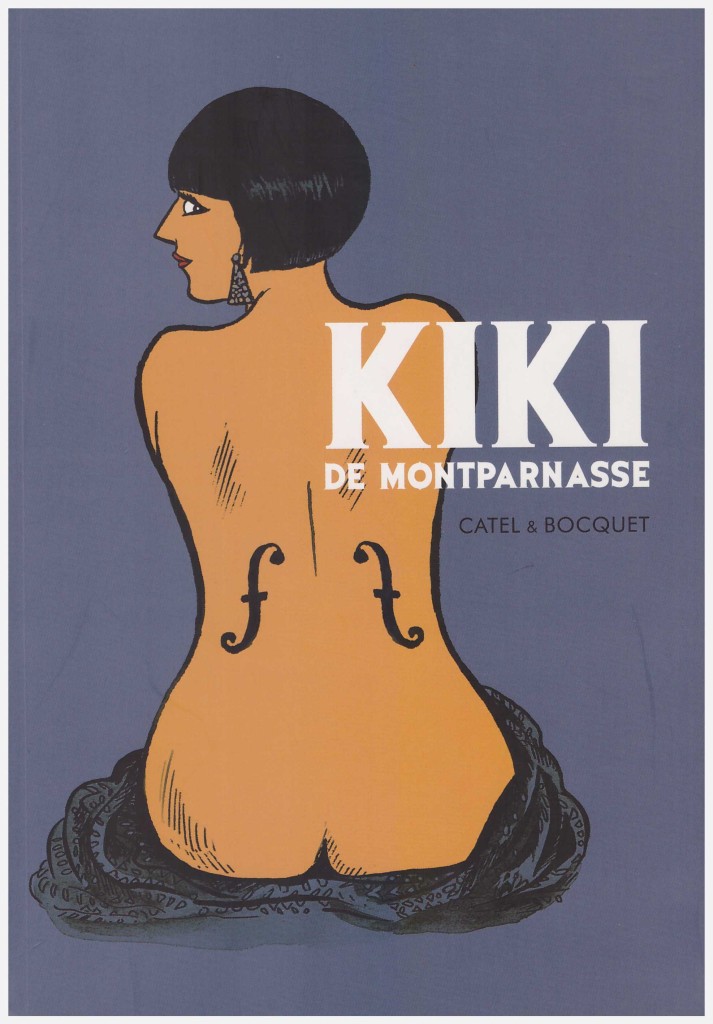

Her lasting fame is not as the talented artist and cabaret singer she was, but as the inspiration for others and objectified in numerous photographs by her lover Man Ray, the most famous of which is drawn for the cover illustration. Her often sybaritic choices, though, inevitably resulted in a prematurely curtailed life. Toward the conclusion a scene relates a chance meeting with Man Ray after many years that occurred shortly before her death. She paints a brave face on her circumstances, and disposes of the money he provides her with. Whether imagined or anecdotal, it’s a heartbreaking sequence.

Catel (Muller) provides some beguiling cartooning. It’s deceptively simple outlines with no shadow, and rarely any shading. Her Kiki is a joyous creation, her sharp nose accentuated, enjoying the life she has and rarely unsmiling for very long. She distinguishes a large cast well, although such is the parade of fame dropping in and out of Kiki’s story, the pages of biographical information at the rear with accompanying sketches are very welcome. There’s also a timeline cataloguing the important aspects of her life.

This is a loving and captivating work accessible to anyone whether or not they’re familiar with Kiki, her era and her friends. In fact, a state of relative ignorance is probably the preferable method of approach. In addition to achieving the prestige of an award at the Angoulême comic festival Kiki de Montparnasse won several other awards in France.

Kiki has bequeathed her name to an exotic lingerie company, and she’d surely have been pleased at her memory being immortalised in that fashion.