Review by Ian Keogh

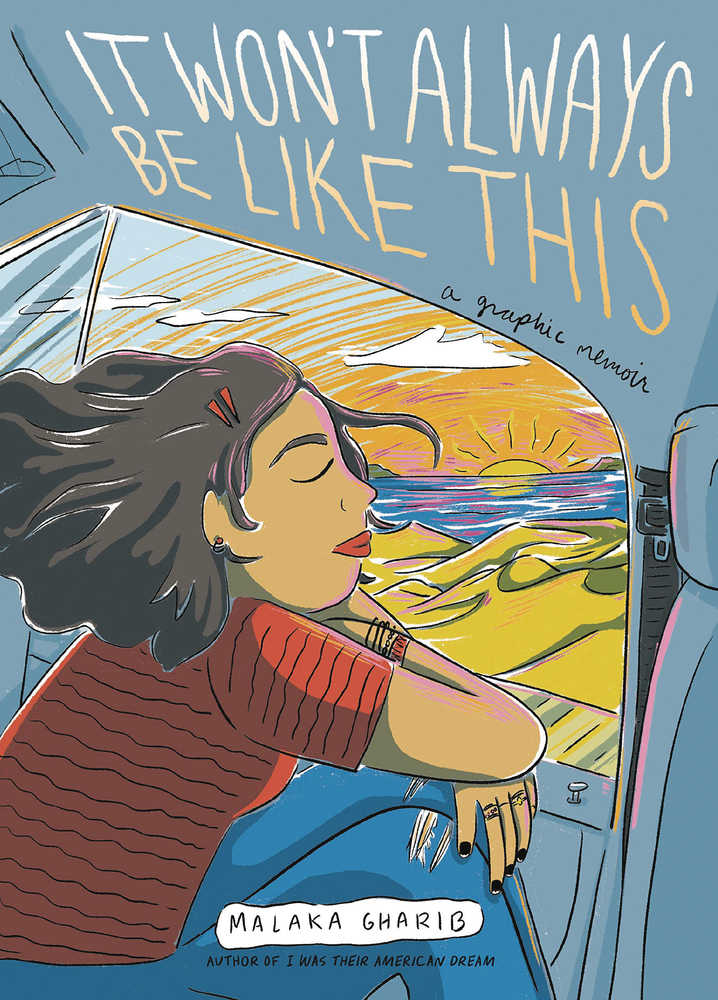

Malaka Gharib’s childhood was first explored in I Was Their American Dream, which detailed her mixed Egyptian/Filipino heritage while growing up in Los Angeles. This follow-up continues the theme of always feeling the fish out of water as Gharib details her summers spent in Egypt, then Qatar after her parents divorced. Her father is employed to manage resort hotels, and one summer she arrives to discover she has a new stepmother. Hala doesn’t speak English, and Malaka’s Arabic is very limited, which makes communication difficult. However, on the first trip, when she’s nine, they find ways to have fun together. When Malaka next returns to Egypt two years later, Hala has given birth to a child and is expecting another.

While there are diversions into other areas, the core of It Won’t Always Be Like This is Malaka’s relationship with Hala, and it’s what makes for a flawed story. Some cross-cultural differences are interesting, but over much of these recollections there’s not enough to the relationship to drag it beyond the ordinary, and while she’s being true to her childhood feelings Gharib’s fleeting mention of items of greater interest are sidelined. At points the child’s natural attitude that what happens in the USA is automatically cooler somehow transmits as patronising, although the cultural imperialism is mitigated in narrative captions written with hindsight. All too many pages, though, deliver lists of bands, clothes or fads that seem designed more as aids for Gharib’s memory later in life and lack any great interest for readers.

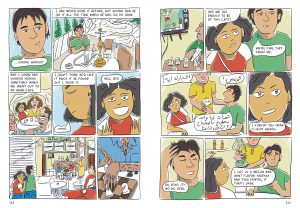

The lack of depth is applied literally to the flat art, which never comes to grips with expressing emotions, reminiscent in some ways of Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s simplicity. When presenting scenery it briefly comes alive, but it’s otherwise functional and no more.

It’s only during the final third of It Won’t Always Be Like This that Gharib’s recollections come to life. By then she’s in her late teens and early adulthood with a wider perspective on the world, able to make her own decisions and take in what other people believe. The differences between the largely devout Arabic communities and the scantier aspects of American beliefs come into focus, and the secondary theme of isolation and alienation recurs at moments. Earlier it rarely transmits as anything more than the feelings of any child of divorced parents on occasion, but now flourishes. A striking scene has Malaka standing up to her father, and the conflicting emotions of love and pride are well handled afterwards, while the right emotional buttons are pushed at the end. That requires greater explanation as to why Malaka wouldn’t make more of an effort to track Hala down, and it exemplifies the concentration on events that don’t really matter in story terms at the cost of stronger material.