Review by Ian Keogh

Iscariot is the keeper of magical memories and a legacy that’s all-but died out as humanity prospered. He’s first seen in a prologue introducing his people and their wistful recognition of reality. Four hundred years later he’s hanging around a cancer ward, in effect performing magical parlour tricks for the residents, apparently lacking greater purpose.

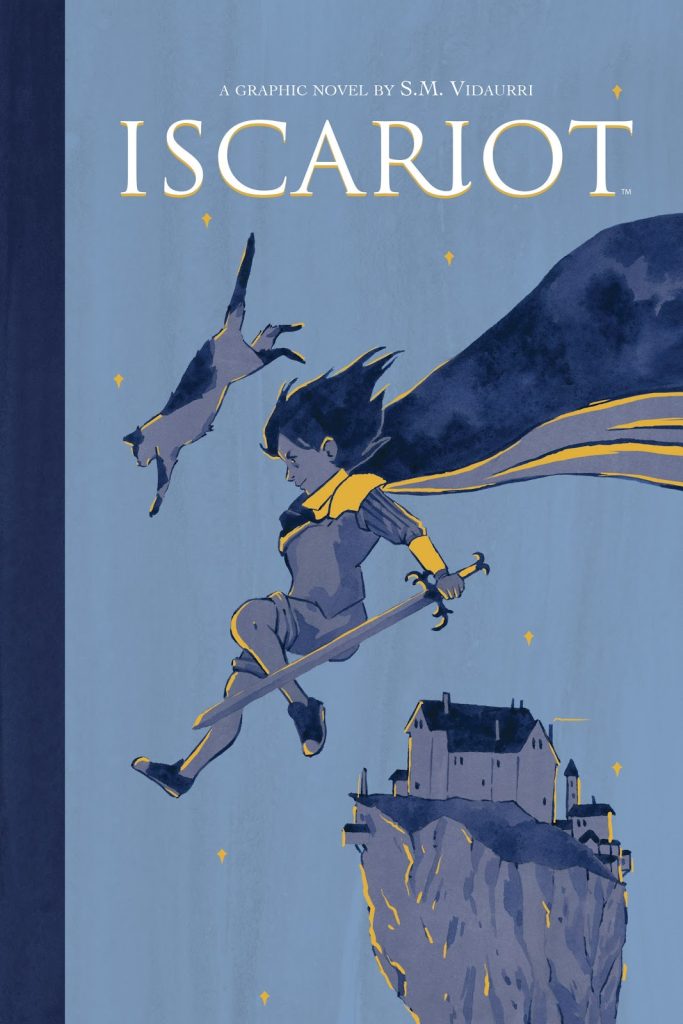

Iscariot seems prepared for the young adult market, and Archaia have pushed the boat out for the production, having the package resemble an old-fashioned children’s book in hardback with little gold foil highlights on the cover. It’s a really nice looking artefact even before cracking the pages open and discovering S.M. Vidaurri’s delicate art.

However, that’s where the similarities between Iscariot and children’s fiction end. Although featuring a child in a leading role, this is no children’s tale, only very gradually disclosing a greater purpose, and until then offering elusive fragments rather than a coherent story. Furthermore Vidaurri’s chosen name for his lead character can’t help but recall Judas Iscariot, Biblical betrayer of Jesus. His visits to the cancer ward seem ever more sinister, especially as they involve befriending children. Primary among these is Carson, a young girl unable to cope with hospital restrictions, and she becomes key to how matters proceed.

There is a betrayal at the halfway point, but in keeping with the tone throughout, exactly whose is uncertain. After it occurs, greater prominence is given to Carson, who’s returned to school after what appears to be successful treatment of her cancer, and Vidaurri opens a discussion on what magic is and how it can be manipulated. That’s the key to everything that’s going on, which amounts to conflicting beliefs about how the world should be run. Even then, though, it’s not a clear parable, nor a straightforward fantasy.

That, in essence, is the problem. Too much of Iscariot is dependent on a belief in the way things ought to be done with no great underlying foundation. It’s ideological rather than empirical, and it’s compounded by a change of heart that plays into the story, but isn’t consistent with the beliefs explained. Themes of reconciliation and redemption are clumsily introduced toward the end, and it leaves Iscariot as a great looking disappointment. It’s intriguing, but average instead of matching the art and ambition.