Review by Graham Johnstone

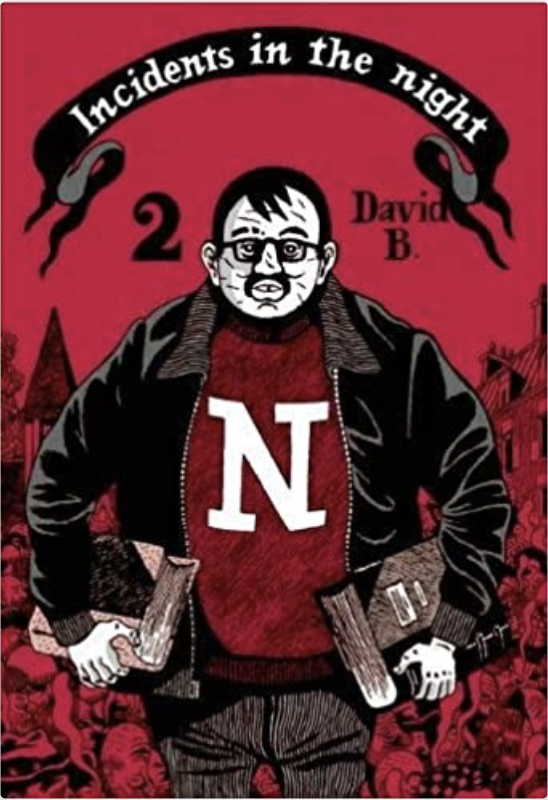

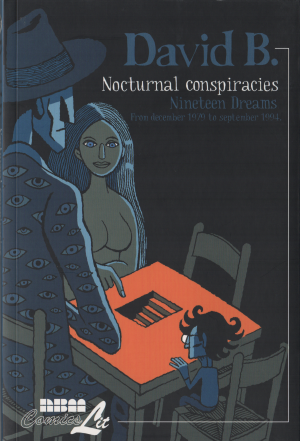

David B’s Incidents in the Night began as a book about ‘David B’ finding a book, called ‘Incidents in the Night’ (hereafter Incidents and ‘Incidents’). ‘David’ dreamt about the book, triggering a quest for copies and the stories behind them. The quest retained the quality of a dream: illogical events, mixtures of the familiar and unfamiliar, and intense involvement. For the real David B, the quest seemed a pretext for an exploration of the creation, collection and curation of books. ‘Incidents’ merged fact and fiction, history and invention. Incidents did much the same, delivering a secret shaggy dog history of Paris and France, and a visionary love-letter to literature.

As this second volume opens, David is missing. He is thought killed by ‘Incidents’ affiliated gang The Fleet. So David’s journalist girlfriend Marie, brother Jean-Christophe, and Police Commissioner Hunborgne, join forces against them.

The plot is looser, and quest more divergent than ever, meandering through a wonderfully invented demi-monde of brigands, beggars and booksellers, replete with poetic names and backstories. Wider events, like a ‘Beggars Riot’ are thought orchestrated by Émile Travers, ‘Incidents’ founder and supposed criminal mastermind. As with any mystery – clues are found that take the story in unforeseen directions, yeilding dead ends or further clues.

At best it’s a marvel of joyous invention. The bookstores offer delightful names and details like The Forgotten Road which, on ascending each floor, gets less accessible, and The Hanged Man, where “no client has ever entered”. The Commissioner’s investigation nods to American sources, with Dick Tracy inspired colourful nicknames and visual gimmicks, like Shark, and Sour-Puss. Travers’ supposed masterplan is a convenient pretext for ever-more divergent threads. Other times the appeal fades, with page after page of factoids, piled atop one another like volumes in a bookstore, liable to collapse on a casual browser. ‘The Dark Age’ section is particularly demanding and readers may struggle to retain a barrage of royal apocrypha unlikely to inform future events. David’s details and detours, are sometimes delightful, sometime demanding.

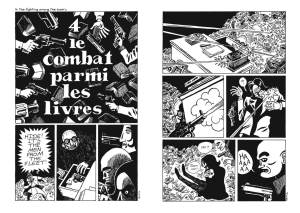

Of course every oblique anecdote fuels some wonderful imagery and penmanship from this restlessly inventive artist. His panels are both impressively intricate, and admirably clear. He once again makes great visual play of the paraphernalia of bookstores, with the cover designs of invented books particular highlights. There’s some powerful imagery, like Jean-Cristophe tearing off Travers’ mask to reveal… successive pages of ‘Incidents’, each teasing new stories with a faux-antique engraving and resonant titles like The Mysterious Barricades. ‘The Dark Age’ section lets B indulge his enduring love of battle scenes and historic militaria that so enriched Epileptic and The Armed Garden. The team of heroes are well designed, and distinctive, with the booksellers and criminals charmingly qrotesque. The detective element inspires beautiful pages of the investigators against montages of dossiers and crime-scene photos. If David the writer occasionally irks the reader, he always inspires David the artist.

What’s now a book was originally serialised, and is perhaps best enjoyed with that in mind: each part a happily acquired treat, to be enjoyed, page after rich page, with little concern for where the story leads. This second volume again ends with a teaser for the next part. A decade on, there’s no sign of it (in English, at least) but in a book about an elusive antique periodical, a teased next episode has a certain charm – a final, playful, metafictional joke.

Artist Jackson Pollock, said of his paint dribbled canvases: “I don’t paint nature. I am nature”. Beauchard is similarly less interested in representing ‘nature’ than the creative flourishes of a restlessly inventive writer and artist.