Review by Frank Plowright

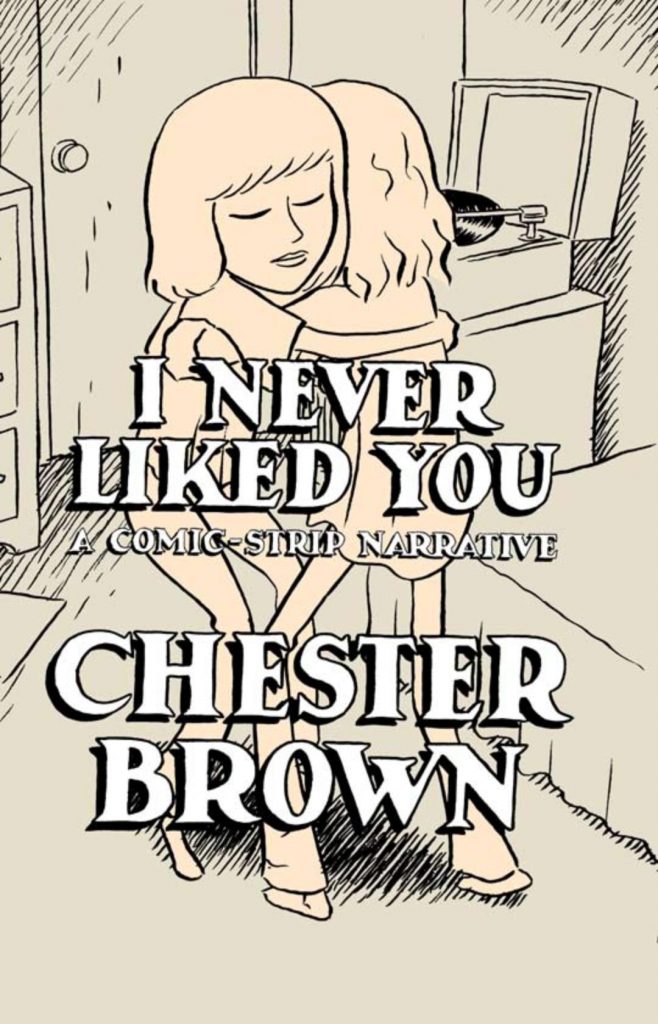

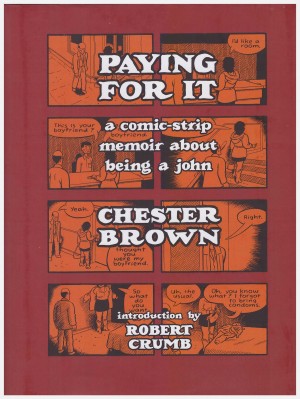

I Never Liked You is Chester Brown purging his memories of an adolescence during which he was shy and withdrawn to a level well beyond most teenagers. He’s uncomfortable with women even when girls at his school and in his neighbourhood make it clear they’re interested, and a succession of seemingly unrelated incidents eventually coalesces into a bigger picture.

This is an early work from Brown, and displays an eccentric sense of pacing. There are times when it’s obvious that a single small panel is surrounded by a large white area for emphasis, or to draw attention to a point. However, on far more occasions the panel placement seems entirely random, although it’s keeping with the both the minimalist ethic and an overstated awkwardness, indicating perhaps that Brown’s personality hadn’t moved on much from the events shown. Beyond a more conventional method of panel placement, there’s little difference between Chester Brown’s 1991 art and that of twenty years later. His tidy cartooning precision and sense of place was sure very early in his career, and the drawings are compact and well composed.

Despite the deliberately distanced approach there’s an emotional intensity to I Never Liked You, but appreciation is likely to be intimately connected to understanding. Brown is never explicit about his internal conflicts. Readers who can identify with his singularly unusual capacity for resistance to girls who make their intentions clear will pick up on subtext and sympathise. Those unable to understand how he can tell a girl he loves her, then almost ignore her will maybe consider we’re not being told everything, or simply dismiss Brown’s internal conflict. Why would he accompany a girl to a film, then be more concerned about what the local bullies think? Is he just a self-absorbed prick?

Some hints occur throughout as Brown notes aspects of his mother’s behaviour. She seems a needy woman, maybe bipolar, who requires the spoken validation of love. A heartbreaking scene is Brown drawing her asking why he can’t even say he loves his mother, and his response being utter silence. There’s a reprise near the end of the book, and what screams out is I Never Liked You being a form of personal atonement. The title is explained, but Brown also shows himself creating a picture with a meaning, then denying that meaning when someone else deduces the truth, so does the title have a second meaning?

It’s the measured depth that makes this a fascinating memoir, eventually, Brown drawing together so many ordinary incidents into something with meaning. He’d go on to explore themes of isolation and awkwardness in other projects, sometimes more directly, but move pass the experiments with pacing and this has a heartbreaking introspection that still makes it a visceral, tormented read.