Review by Graham Johnstone

The first volume of this expansive history of hip hop took us from the 1970s roots in New York’s poor South Bronx to 1981, when the music started to break through to the mainstream. This book covers the busy years from 1981 to 1983.

We pick up many of the characters from the first volume: not just rappers and MCs, but also graffiti artists, movers and shakers, managers and club owners, record companies, and so on. It’s well named Family Tree: this is the story of dozens of people uniting in groups, splintering off, forming new groups, crossing from label to label, and so on.

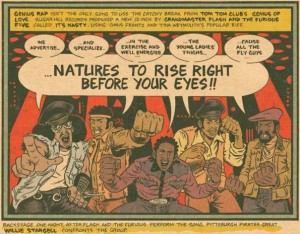

Here, we get the story of the early hit records, by Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, and more. We also find out about the repeatedly sampled sources: Jerry Lordan’s guitar riff from Apache (in Britain a hit for the Shadows) and the keyboards from the Tom-Tom Club’s Genius of Love.

At this time hip hop was crossing over into other media and channels. Fab Five Freddy organises an exhibition of graffiti based art, which includes Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat – future hot properties in the gallery world. There’s extended coverage of the making of the film Wild Style, a good story involving a shoestring budget, a real shotgun, and being chased by the police for spray painting.

Hip hop is also spreading from Boroughs of New York, notably to Compton, California, and across to Europe. There’s the first rap record in French, but made in New York, and controversial Punk Rock impresario Malcolm McLaren flies people to Britain to make unlikely crossover hit Buffalo Girls.

Piskor keeps a lot of plates spinning, following the progress of the different key players through the years. He also drops in on people before they make their mark. Here we meet the guys who’ll ‘become’ Dr Dre, and Public Enemy, and the Beastie Boys.

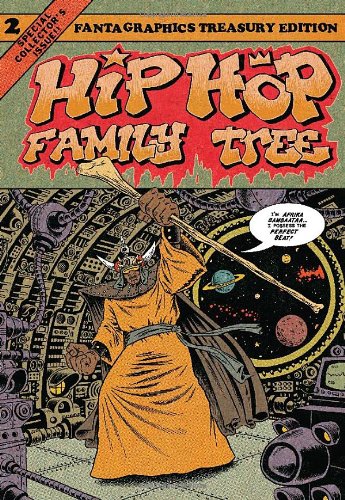

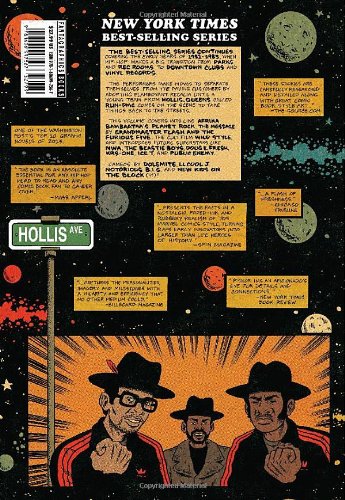

As before, the strips are drawn to look like 1970s comics: greyed-out blacks, flat colours with visible dot patterns, and all on a yellowed newsprint effect background. The printed versions take this one step further by mimicking the size and styling of Marvel Treasury Editions from that period. There’s also the clever device of having a few panels featuring quotes from the 1990s printed in vivid, contrasting bright colour.

The artwork may not immediately impress, but Piskor’s skilled. He can draw the dozens of different characters distinctively, and captures the outfits, the poses, the moves, and he crams a lot in. A single panel on page 18 shows a stage with all four strands of hip-hop: DJs choosing and spinning discs, an MC on the mic, break dancers, and graffiti artists. The facing page has a panoramic thriving dance floor, and a panel highlighting key people in the crowd at the Roxy club, unaware others around them will go on to be key players. He gives us convincing drawings of the props: reel-to-reel tape recorders, and the iconic Roland TR-808 drum machine.

Piskor’s adept at capturing raps on the comics page, for example by putting each line in a different balloon, putting the rhyming words in Bold, and so on. He captures the effect of the Furious Five’s solo and harmony on Genius Rap, with individual word balloons for each one’s part and a shared balloon with big lettering for the group line.

Hip Hop Family Tree is a great idea, brilliantly realised. It’s well researched, with a massive amount of history, anecdotes, and little telling details effortlessly squeezed into these hundred lovingly drawn pages.

This is now also available slipcased with volume 1 as Hip-Hop Family Tree 1975-1983.