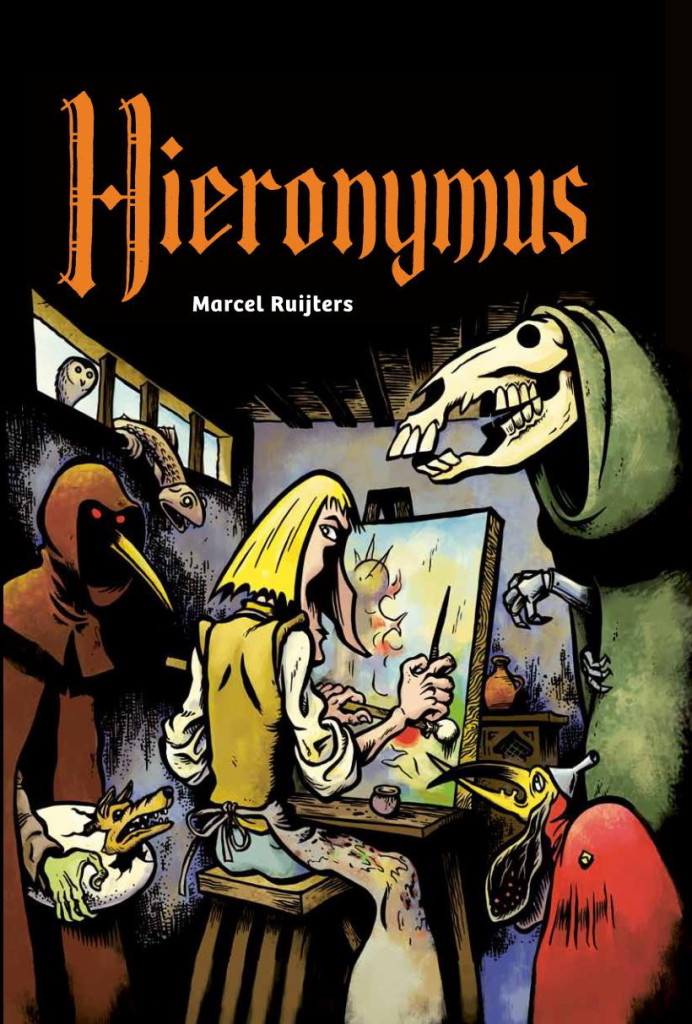

Review by Frank Plowright

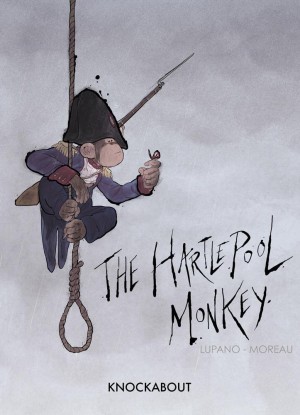

As the cover and title indicate, Dutch creator Marcel Ruijters takes as his subject one of his country’s most famous artists and weaves fictional biographical occurrences around the few sketchy details known of his life. This was spent, as far as anyone knows, almost exclusively in the town of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, where he remains the most famous resident 500 years after his death, although a disproportionate number of kickboxers may beg to differ. This book was commissioned by the organisers of a year long festival in the town celebrating the 500th anniversary of his passing in 1515.

The opening sequences see Bosch already a married man, earning a living from his art in a studio shared with his brothers, all heavily dependent on the exacting Domincan monks for commissions. While quite sceptical about the manipulation of religion, Bosch nonetheless believes the visions he receives, attributing them to some higher power, and acts on them.

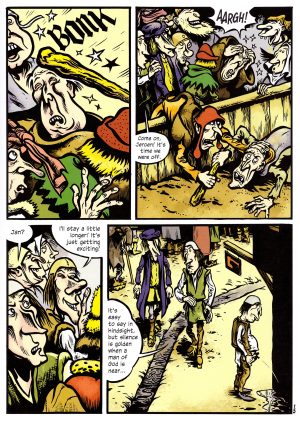

Because so little is known of Bosch’s life Ruijters extrapolates around events known to have occurred in the area during it, providing a poignant insight into life at the time. In a community only able to fight fire with small buckets of water it will have a devastating effect, and Bosch is depicted recalling one from his childhood, his father’s priority being to save their artwork. Elsewhere Ruijters portrays Bosch wandering around the town sourcing images now known from his paintings, their disturbing quality diminished when isolated among the everyday. Bosch discusses the recent advent of the printing press, evades the leper colony, visits the alchemist, sees a man hanged for copulating with a pig, and the view from a cathedral under construction, and witnesses the primitive medical practices of the time among other experiences.

Artistically Ruijters resembles a more restrained Hunt Emerson, which explains his attraction to Knockabout, and his signature technique is stretched faces with long straight noses. The comedic style draws the sting from events we’d now consider barbaric, yet were 15th century forms of entertainment. Among others we’re treated to men tortured before being hung and blind men fighting a pig. Having spent most of the book isolating Bosch’s disturbing images in everyday surroundings, Ruijters really comes into his own with the final sequence in which the images feature in a nightmare.

This is educational in the most painless sense, impeccably researched, enlightening about the times and features the bonus of explanatory notes. What’s not to like?