Review by Frank Plowright

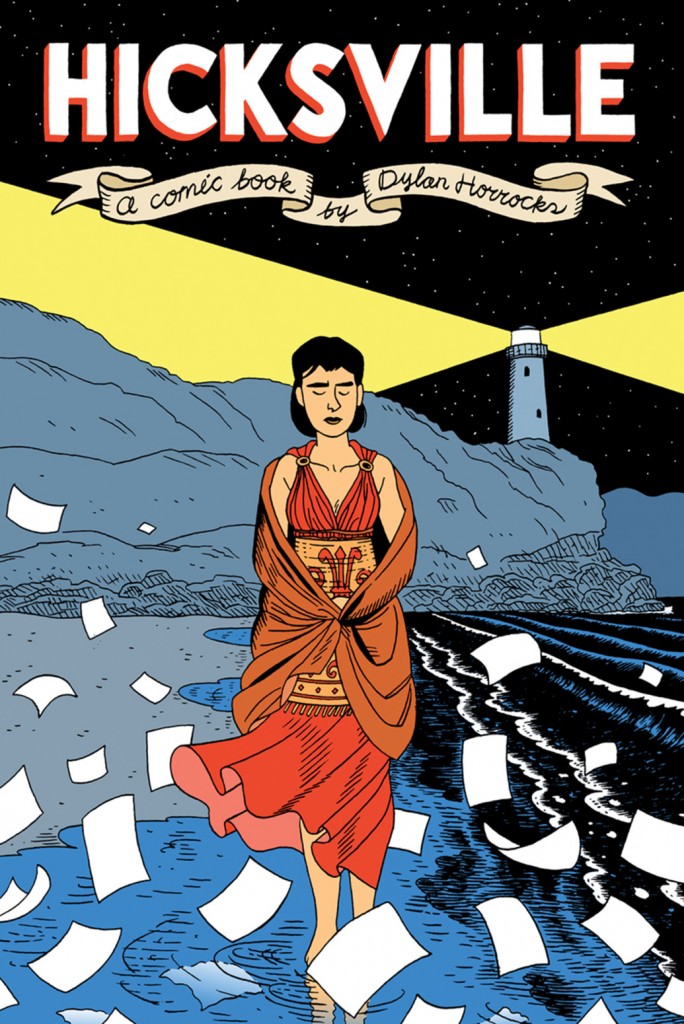

Hicksville is a rich, rewarding and immensely emotional statement about the power of comics as a form, eschewing genre classification. Dylan Horrocks switches styles to induce an atmosphere of magical realism and there are knowing nods to the comics world, at least as it was in the mid-1990s, which are often very amusing. Yet distance and progress, such as the web-comic, in no way undermines this love letter to print.

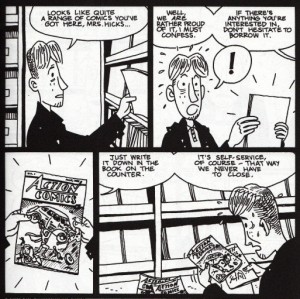

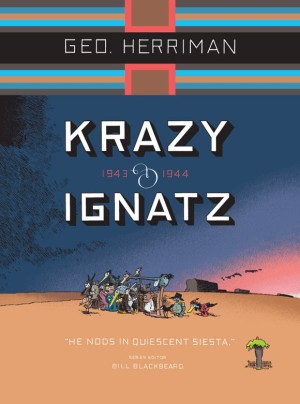

At its most linear, Hicksville is the tale of Leonard Batts, a self-important comics journalist who’s travelled to New Zealand in order to research Dick Burger in his remote home town. Burger has parlayed status as a hot superhero artist, viewed as the heir to Jack Kirby, into a multimedia empire, but is unwilling to talk about his past. He’s a divisive figure in his birth town. That, though, barely scratches the surface of a small community where comics are revered in all forms. The local bed and breakfast is run by Mrs Hicks, a lady of late middle-age who further manages the town’s comics lending library, orders small press comics from Finland, and makes costumes for the annual Hogan’s Alley beach party.

Horrocks splices the story with samples of work by Burger and his forebears, depressed humour artist Sam Zabel, and a strip about Captain Cook and the settlement of Hicksville revealed in chance snippets, always with a timely comment on Batts’ current situation. There are also pages from an odd comic in an Eastern European style hybrid language by Cornucopian cartoonist Emil Kopen, and an affecting sequence where torn between two lovers Grace hears his thoughts about artistic creation.

The centrepiece is ostensibly a mini-comic by Zabel, Burger’s childhood friend, relating how he attended Burger’s ostentatious 30th birthday party, and how temptation was dangled when he’s flown to Los Angeles to see Burger’s comics factory. There is a catch. It’s also Horrocks’ savaging of comics as product, stepping stones to other media rather than objects of intrinsic worth. As Batts reduces his reception from Arctic to frosty, reasons for antipathy towards Burger are clarified.

Such is the trainspotting appeal of Hicksville to regular readers of comics, there’s a tendency to ignore the parallel love story. Grace left Hicksville with a wounded heart, travelled the world, indulged her botanic interests, yet has returned as conflicted as ever. She’s an intriguing character who in some ways represents the purity of vision without compromise, yet that also comes at a cost.

The whole is meta-fictional commentary, and in this manner the intimacy involved in the construction of Hicksville the town is as much wish-fulfilment as any superhero comic. The financial worth of individual comics is an irrelevance to Hicksville denizens, and the freeing of art from commercial needs is reinforced. Although a prelude features Horrocks himself, in many ways Zabel appears to be a stand-in, and Horrocks’ new introduction to the current edition clarifies how much of himself he poured into Hicksville.

It’s unlikely that anyone with no knowledge of comics will work their way toward Hicksville, but should that be the case, a detailed glossary is provided, also noting cultural references to New Zealand.

Horrocks supplies a telling quote from George Herriman as his closing note: “Real or unreal – fact or un-fact – it was a beautiful vision”. Whether the quote sums up his work, or he constructed the work around the quote, Hicksville lives up to it.